You might think, at the root of Heavy Rock lies power and chauvinism. Misogyny and male supremacy. Judging from some excess trends in heavy rock, later. With lyrics like “the soul of a woman was created below” (gleefully sung – though not written – by Led Zeppelin on “Dazed and confused”).

The truth is different. At the core of heavy was a mellow part. Even a feminine part, and sometimes a feminist perspective. This was in the early days of heavy rock, what we might call the “proto” stage of heavy. A this time, it was a tendency in rock, not yet a separate genre. Rock music was the key part of a counter culture which was still quite cohesive, not yet split up into music genres, different politics, or beliefs. Basically it united everyone under their long hair. Young men as well as women. It was OK for men to display more feminine traits, like expressing feelings and growing their hair long, like women. It was a case of the young and the new, against the old. With long hair and rock music as main symbols of the new. This was soon ridiculed for being childish and naive (a debatable point, compared to the more politicized counter culture later), and is important to understand, for why “mellow” came into the heart of “heavy”.

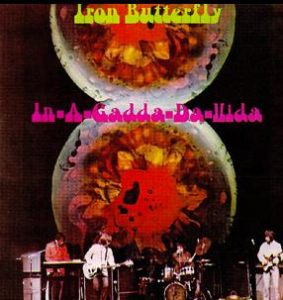

This mellow core of heavy is very evident on one of the first early heavy rock albums, Iron Butterfly: Heavy. Released in January 1968, before the debut albums of Deep Purple (July 1968), Led Zeppelin (1969), and Black Sabbath (1970) – the giants that later defined the heavy rock field. Things changed fast in those days, and before Iron Butterfly, what mainly existed was the “noise rock” of Cream and other blues-rockers. “Heavy” made heavy rock into a more distinct part of rock music, even if it was only in “proto” form, not fully realized.

The seminal Heavy album starts with two songs that criticize current society. One is about possession and property. The other is about going beyond that paradigm, going “beyond conscious power”.

So in fact the world’s first heavy rock album starts with a critique of the sense of possession, in love life, with these lines:

“When a man has a woman

And he doesn’t really love her

Why does he burn inside

When she starts to love another?

It’s possession

It’s possession

It’s possession

It’s possession”

The song isn’t just about possession in general, but about men’s feeling of possession, or in a more recent term, men’s feeling of “entitlement”. Even if the man does not really love the woman, he cannot take the rejection from her, and that she gives her love to another man.

Instead, he burns inside.

Why? It’s possession. The song refrain resembles a chant, a drone. Like a message burned in, through heavy chords and threatening music.

So, starting from the number one song on the first heavy album, we find a critique of masculinity and possessiveness. Associating men, property and fake love.

The album was recorded in autumn 1967, in the context of the turbulent and hopeful youth revolt of 1966-67, before the year of struggle and defeat, 1968. Youth were waking up everywhere. The proportion of long-haired among young men rose exponentially. Non-violent change methods were tried out on a large scale (like sit-ins, street theater, new forms of art, new economies). It looked like the authorities could accept the changes. “Socialism with a human face” was rising in Checkoslovakia.

You need a calendar to interpret these and other rock classics from the period, since the mood changed fast. 1966-67 was quite different from what came later. This is well brought out in John Savage’s book “1966” (Faber and Faber, London 2015).

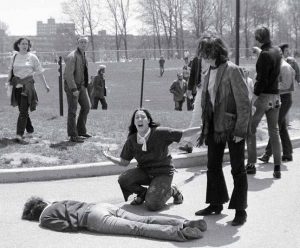

1968 was different and in many ways a shock. First, the counter culture / new left was defeated through street battles in Paris in May 1968. Then, in August, the Soviet Union invaded Checkoslovakia and squashed the new left-liberal democracy. The setback occured in the US and other countries too, in different forms, with the murders at Kent University in 1970 as the most symbolic event in the US.

Different rock bands and artists developed different responses to these events. What is common is a change of mood, due to the defeat. Some bands, like Steppenwolf, developed more political lyrics, like the critique of US capitalism on the album Monster (1970), and feminist lyrics also (e.g. For ladies only, 1971). Jefferson Airplane’s Volunteers (1969) was still vaguely hopeful, and similarly “revolutionary” in its view of society (with lyrics like “throw down the walls”).

For interpreting rock music classic albums, having a calendar or a diary at hand is a must. Even better, with in-depth music histories, like the Savage book.

Compared to groups like Steppenwolf, Iron Butterfly’s lyrics were less overtly political, keeping to the early counter culture message of going beyond ordinary politics (since this was associated with the establishment and the adult world). The music at the time reflected split opinions and diverse experiences in the counter culture, with some parts drifting towards more militant, adult and (traditionally) political response. Again, arguably, with very mixed results, or indeed rather bad results, even if the former youth revolt ideas were somewhat childish (e g Pink Floyd, with child-voices: “Why can’t we play today”. Why can’t our dream just become true).

Political and feminist lyrics, in the songs of Iron Butterfly, were more like an undercurrent. They speak like “heads”, in these songs. On this – maybe naive and childish – level, the song “Possession” spells out the problem, or a main part of it. The next song, “Unconscious power” points to the solution.

(The cover shows keyboard and singer Doug Ingle, main composer and writer, somewhat alone – on the other side of the great monumental ear in the middle)

(The cover shows keyboard and singer Doug Ingle, main composer and writer, somewhat alone – on the other side of the great monumental ear in the middle)

“We all want to prepare you

The unbelievable is going to happen

It will linger in your mind forever

Let this carry you wherever, wherever

Triggering the unconscious power

Removing all your inhibitions

Releasing complete freedom of thought

Sensations of every sense will prepare

With this you will see every thing

Triggering the unconscious power

Triggering the unconscious power

I say to you nothin’ for now

For now we know all

We know all

We know all

We know all”

The lyric is very optimistic, something unbelievable will happen. It strikes the tone of late 1960s optimism. And the change will be large, it will linger forever. You should let this knowledge carry you, wherever. Triggering your unconscious power.

Sounds superficial? Well, it was before “new age” ideologies. Here are young long-haired men trying to psychoanalyze the world. Very limited, it may be said. In fact this was often said, at the time also, about the “childish” and “simple” aspect of the youth revolt and early counter culture. It was basically naïve. Some counter culture artists like Frank Zappa contributed to this idea. Hippies were all fake.

But note what these two songs are doing.

First, they are musically far from hippie territory. There is a feeling of anxiety and even terror, not a cozy “summer of love”, in the music (a worthy runner up is Blue Oyster Cult: This ain’t the summer of love, on the album Agents of fortune, 1976).

There is the typical impatience of the late 60ies – go right to the core. Just play, even if you don’t know how to do it.

They dig into a feeling, a burning inside, something many people recognize, not least, men. They start with a widespread experience, a phenomenon. They describe it vividly, like the pop art emerging at the time. It’s concise. They don’t make extra words, or opinions. They just jump right into the explanation. This burning has to do with possession and property. They describe men’s sexual jealousy and sense of property as a disease, even if they don’t use that term.

It was certainly enough to make long haired parts of the youth of middle-class America and elsewhere wake up, even if it did not make a hit. The band sold millions soon after, with the album “In a gadda da vida” (1968). Many Iron Butterfly songs are harsh condemnations of an oppressive society. “In a gadda…”, as a contrast, had a positive message, pointing to a better future. It caught the imagination of young people in the US, becoming a marker of youth culture influence.

This ability to catch “surface” phenomena, and (to some extent) point to better solutions, was a main reason why youth and counter culture movement expanded rapidly from the mid 1960s onwards. Like using the long hair to go beyond traditional political divides. The tendency was leftish, but this was to be the “new” left, not the old. Within the youth movement, 1964-67, the main target of critique was very broad, it was the adult world, fake family life and consumer society (Frank Zappa: “plastic people”), rather than a specific (adult) political target like capitalism or class. Gender was also mainly implicit, even if the young men growing their hair longer were soon ridiculed for “looking like girls”. The underlying feminine / feminist current of the 1960s changes has not been sufficiently studied.

So why does Iron Butterfly close their “Unconscious power” song by saying “I say to you nothin’ for now”? And repeating this point? This can be interpreted as “headspeak”.

The notion of the “head” was important in the counter culture. Heads were thinking people or intellectuals guiding the movement, but they should not become a new upper class. So for a head to withdraw, and say, I say nothing for now (since we are right at the beginning), could be the right thing to do. Very cool. Rather than preaching or predicting. The message in the song is very clear: you can see for yourself. “We know all”. If only we let in our “unconscious power”.

A major counter-argument, to what has been said before, is that Iron Butterfly’s “Heavy” album does not really represent the birth of heavy rock. For this, one should listen to albums like the first Black Sabbath album, instead.

This is true on one level. The “heavy” sonic signature is more recognizable here, than on Iron Butterfly’s Heavy. Black Sabbath goes in the direction of “doom and gloom” – towards heavy metal, and dark metal, the notable 1970s trends. On the other hand, they also lean backwards on the blues of “noise rockers” like Cream. Not very inventive, compared to the best Iron Butterfly melody lines, although more distinctive and genre-defining. Bands like Procol Harum also picked up some of the doom and gloom trend, although they cannot be classified as founders of heavy rock.

However, even if Black Sabbath was maybe the first to trademark an “evolved” heavy sound, other bands evolved in other ways, and the “first” position can be questioned. If we allow the scope of “proto” heavy, the roots of the genre, Iron Butterfly’s first album stands strong.

For understanding the evolution of counter culture music, The Byrds is a useful case. Even if it did not evolve into heavy rock, but rather, early “Americana”, country and western influenced music.

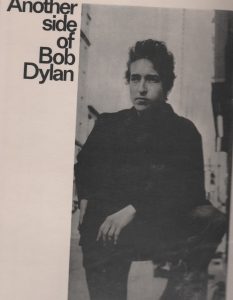

The Byrds was a key link, making mid-60ies folk music into folk-rock-pop hits. They started out singing Bob Dylan’s songs, making a major hit with a pop-rock version of “Mr Tambourine man”, with several weeks at the top of the single sales lists. This was followed up by others, like “All I really want to do”, “My back pages”, and “Chimes of freedom”. However, the public gradually got tired of the somewhat stereotypical Byrds treatment of Dylan’s songs, and sales dwindled. Still, they managed to get his main message across, as a foundation for further rock development. Dylan took up the challenge, one might say, with “Like a rolling stone”, and others. Dylan’s insights came to stay, in rock music development, partly thanks to the Byrds.

The Byrds took much of their material from Bob Dylan’s “Another side of Bob Dylan” album, 1964, in some ways his most revolutionary or radical album, still keeping to his “protest” roots.

Do you think the “mellow core” of heavy rock is only a special back-then case? Don’t be too sure. There is more “mellow stuff” lurking behind the hard, heavy and metal doom lyrics and headlines. This is the subject of another blog post, but two recent examples deserve mention.

Rammstein, on their recent (untitled) album (2019), sings about the abuses of German power through the times (Deutschland) and the violations in the name of religion (Zeigt dich). They are critical, but also mellow (Radio).

Opeth, on their last album “In cauda venenum” (2019), are similarly critical, with some doom and gloom as behoves the genre, but they are also mellow, for example in the track Dignity (Svekets prins), using a sample from prime minister Olof Palme’s new year speech, some years before he was murdered. Palme talks about the inner anxiety (uro) one feels, even if social democratic society seems to go well. Opeth – bless them – takes it on, from there. Here there be tygers.