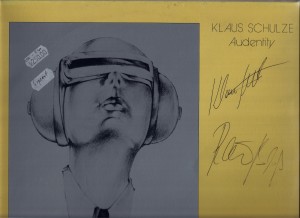

Klaus Schultze: Audentity (1983). Innovative communication KS 800025-26 (2xLP – photo: signed copy, bought at Ringstrom in Oslo, August 2014).

The title may be a little pretentious, but this is a very good double album.”Audentity” – well, in a sense, yes, it is about audio identity. The songs are symphonic works, up to 31 minutes per LP side. The musicians are really allowed to stretch out.

Instead of poor orchestration (typical of progrock etc), we just get Schultze (“computer and keys, program”) and Rainer Bloss (“sounds, Glockenspiel”) doing several synth voices, replicating an orchestra, and if this is a little limited, it is also often rewarding and fresh. Moreover instead of a drum machine we get Michael Shrieve, excellent on drums as always. Besides Schultze, the album’s biggest surprise is Wolfgang Tiepold on cello, who offers much of the orchestrated feel, playing stellar complex cello along the way.

The Beatles is a major indicator, for this purpose, 1963 onwards.

They were the greatest thing happening for music, at the time. Artists and producers tried to succeed, according to new standards set by the Beatles.

At this date – February 14 – i do not have a full data material on the Beatles. However I have some material.

One analysis of the way “love” is treated in Beatles songs, suggesting three main periods:

1 Mixed – communal. E g She loves you, which not only tells of a woman active, loving a man, but another man, lovingly giving the message. A mega hit of all time, due to this special angle.

2 More troubled – from I feel fine, to Ticket to ride – also gradually, more private, less communal or collective. Increasing misogynism.

3 More reflective – from All the lonely people, She’s leaving home, and onwards. Less directly realist, more widely experiental. Reduction of misogynism.

Later we heard J0hn the main Beatle like he was divorced, Paul happy with Wings, and so on. But I think these were the three main Beatle stages.

“Why don’t we sing this song all together

Open our minds let the pictures come

And if we close all our eyes together

Then we will see where we all come from”

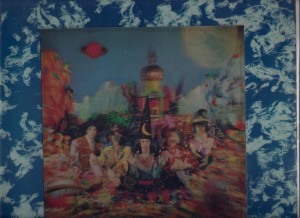

There is not much misogynism that I can hear, on this LP, with the demanding title: Their satanic majesties request. This album was released later in 67, after the three albums described in my first blog post on this topic.

There is no mistake – they really tried to re-adjust their course. I have the original UK LP with the 3D cover. Mick in the center is visible from all angles while Brian is mostly invisible. Brian contributes much to the sound however, a bit like Eno, later.

Richie Unterberger, at Allmusic, writes: “Without a doubt, no Rolling Stones album — and, indeed, very few rock albums from any era — split critical opinion as much as [this ..] psychedelic outing. Many dismiss the record as sub-Sgt Pepper posturing; others confess, if only in private, to a fascination with the album’s inventive arrangements, which incorporated some African rhythms, Mellotrons, and full orchestration. What’s clear is that never before or after did the Stones take so many chances in the studio. (Some critics and fans feel that the record has been unfairly undervalued, partly because purists expect the Stones to constantly champion a blues ‘n’ raunch worldview.) ”

The album was not seen as successful. The opinion of the day, in the music press, was that the Stones should get back to their roots. They had been misogynist before – but in my interpretation, it was mainly after this “slap in the face” reaction to Their satanic… – and the death of one of their members – that they developed this into a more general “sneering attitude”. Thereby the band changed their direction (Sympathy for the devil), contributing to 1970s misogynism in rock music, beyond attitude, as staple fare.

After some years they tried to stop this, in their own records (e. g. You can’t allways get what you want, A fool to cry, Waiting for a friend, and others), yet it was not much heeded, since at the time, the Stones were gradually falling out of fashion. and had become marginal, to pop/rock in general.

A rolling stone?

I was surprised, recording digital versions of my LPs Around and around (1965), Aftermath (1966) and Between the buttons (1967) recently, how mysogynist the Stones were at the time.

It is not just “who needs yesterday’s paper, who needs yesterday’s girl”. It is “Under my thumb” (“the girl who once had her way”), and much else. It smells bad, worse than I remembered. Together with some stylted upgrading of idealized women (“my sweet lady Jane”), the main impression regarding women is that they should be distrusted and kept in command.

True, this was not the main message of the Stones – the main message was one of revolt. But it was part of the “sneering revolt” attitude. No longer the idealized love of the Beatles – love in more low-down ways.

Although the Stones got their largest hit Satisfaction from a text deriding consumer society rather than women, other hits (e g All over now) have misogynist traits. True, the Stones got some of it from the traditions they followed, but there is no mistake, they gave it a further twist too.

However – why is it that misogynist traits in music from this period sometimes go together with the best music? I don’t know. This is a private rule of mine, since it happens on several records (e g Deep Purple: “Why did not Rosemary ever take the pill”) from the 60s and 70s.

I think, perhaps it is not misogynism, this is not what actually happens in the music-making, it is more like a bit daring text, or some other element of revolt, also against women, the things close at hand, as well as society. These are actually two very different aspects, although they have often melted into one. It is only the first revolt aspect that actually engages the good music. Misogynism as a longer term proposition instead tends to stifle artistic creativity. This is my hypothesis.

Later, the Stones tackled life crises and more gender-equal relationships like everyone else, sometimes with depth and perception (You can’t always get what you want; Black and blue; I’m just waiting for a friend). But at the time, in the 1960s, they were the great “opposition” to the love theme of the Beatles, a more working class and less women-friendly version.

“We want Rolling Stones, Beatles go home, yeah yeah” was a slogan here in Norway. The Stones and the Beatles both stood for a new “free” sexuality. But the Stones were associated with “macho” tendencies in the youth revolt of the late sixties.

One could say, the Stones had balls, they tackled this dilemma by the horns, creating songs like Sympathy for devil. “Please allow me to introduce myself – I am a man of wealth and taste”. This is not, actually, so far from Roy Harper: I hate the white man, or other critical songs at the time. Even if it is not Leonard Cohen: Suzanne.

And there is no telling, whether things would have been better, with a more feminist attitude in the band. I think so. Yet according to the morale at the time, it could have meant a less intense, less good band. E g in the direction of the US band Bread (quite a horrible thought. Or a UK version of Jefferson Airplane – doable, but not likely in this setup). The Stones did try the psychedelic direction, including more madonna-like portraits of elevated femininity, without much success (Her satanic majesty’s request). Go back to where you sneer, seems to have been the main reaction – back to your roots.

There is the possibility that the Stones were not mainly recording their own sentiments. They were just doing their best as critical pop-rock musicians, musical journalists – more obviosly so, in songs like Mother’s little helper – recording the sentiments and happenings at the time. This is not all there is to it, but it does connect to a major part of the code at the time, and deserves a hearing.

Together with the assumed “misogynist” texts we find much youthful suffering and will to establish a relationship (e g Time is on my side). The so-called misogynist statements are partly derived from an older blues context and should be seen in a wider context. At the time, it was age and class rather than gender that governed the attentions of the day. The Stones’ early output was part of an age revolt, a youth counterculture, not a gender revolt.

Even so, however, the background misogynist pattern, and the chosen “sneering difference” from the more optimistic love message of the Beatles and others, become more obvious, listening to their 1965-67 albums once more, in 2014.

[NOTE: Raewyn Connell and Michael Kimmel have mailed comments to this text – to be updated]

Jeg fikk Mannsprisen 2013 på et arrangement på Litteraturhuset i Oslo 25.11.13 arrangert av Mannsforum. Jeg er bare delvis enig i Mannsforums synspunkter, men begrunnelsen for prisen var bra – det var en takk til meg som kjønns- og likestillingsforsker. Derfor sa jeg ja.

This new anthology (in Norwegian), edited by Berit Brandth and Elin Kvande and published by Universitetsforlaget / University press, Oslo, is the most thorough overview of research on the father quota in Norway so far.

I have written one of the chapters, discussing the idea of the father quota as an “export item” in Europe. This is not due to “socialist” thinking – but mainly the fact that quota type reforms work out, while other types of reforms don’t work out. They don’t give the same clear results. Therefore, the father premium / quota principle is being introduced or discussed in many European countries today – using different terms, and in different contexts, under right wing as well as left wing governments.

I am reading “Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin”, where the American historian Timothy D. Snyder creates a convincing and new portrait of what the World War 2 was mainly about. Perhaps it does not “change our view of the 20th century” but it is certainly interesting reading, even for a reader who already has a couple of shelf meters of literature on World War 2 and has for long understood that the eastern front was decisive. Snyder laconically tells of death numbers, this can be a bit repetitive, it takes a while before the message sinks in. He shows the suffering of Poland, right in the middle of the “bloodlands”.

From the Nazi side, this was a race war, Snyder reminds us, not just a geographical war. And especially, it was changed into a race war, as the geographical war did not succeed. Victory over the Jews through the holocaust became the absurd “answer” of the Nazi regime to the lack of real war victories. Snyder makes a good point here. He calls it “surrogate victory”. He also makes a good point that Hitler was able to learn from the already established Stalinist killing methods, although he could have added other sources of inspiration also, including British methods of subordination, perhaps American. The Nazis generally were willing to learn from anyone regarding killing.

Perhaps Snyder overdoes the Stalin-Hitler connection a bit, although he wisely does not move into a conspiracy terrain. These were different social processes, even if they both ended up with unheard-of numbers of dead people. Ann Applebaum in Gulag – a history draws a line between a system that kills people on and off, like the Gulags, and a system designed for death, like the Nazi Holocaust, and she is right in my view. What Snyder contributes is evidence of extensive politically motivated murdering in the Soviet Union long before Hitler had much power to kill in Germany. People were not just put into Gulags, many were shot, with quota methods. Death by starvation was used as a method, whole regions could be starved to death.

Snyder’s portrait of Stalinist policy from the early 1930is is frightening, confirming the reports of Victor Serge (The Course is Set on Hope, described elsewhere on this site, writing about the great terror at the time.

Ironically, the evidence is also much in line with Marx’s theory (e.g. in Grundrisse and especially in “Results of the Immediate Process of Production”, appendix to Capital Vol. 1, Penguin, Harmondsworth 1978) regarding how modern power systems develop. They develop socially, before they become industrial – in Marx’s terms: formal and real subordination. Snyder’s new evidence on extensive Stalinist shootings fills out Applebaum’s Gulag evidence at this point. As more people were shot, the Gulag inmate status sunk from “erring comrade” to “enemy” and from there to “vermin”.

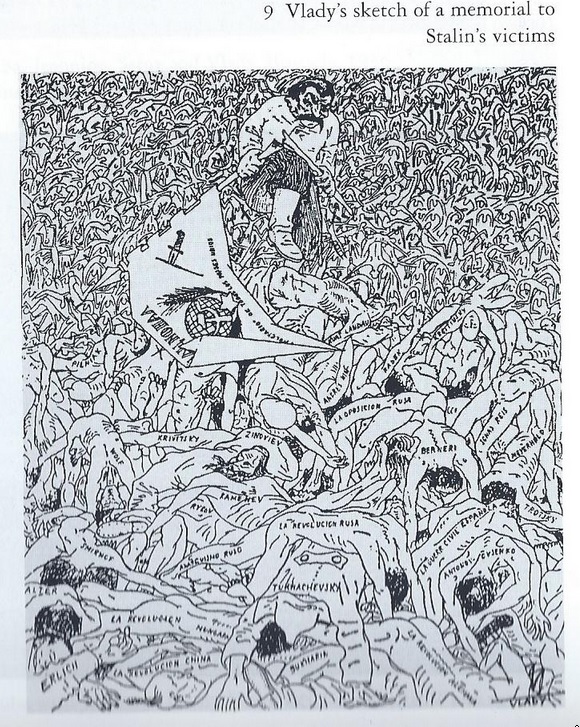

Here is a Vlady Serge (Victor Serge’s son) drawing from this book. This figure sums up Snyder’s new work regarding “socialist” Russia long before today’s historians could get the material. Snyder rightly calls the mass murder a counter-revolution.

The artist, Vlady Serge:

On (re)discovering Kevin Ayers

Some of his music is very intense, and has great complexity and depth

(Kevin Ayers, 1972 concert)

Why pick up Kevin Ayers? Well, he died 68 years old in February and I was sad by this news. His songs are not closed, not polished, but open, or opening up in hazardly and unexpected ways. There are good reasons to rediscover his music. Ayers grew up partly in Malaysia, was a friend of Syd Barret (Pink Floyd), and liked the “whimsical” attitude of the best English pop music.

I thought I had heard most of it when it came out, from the late 1960s onwards, and I probably did at friends’ places and at parties, but it turns out I only had tapes of two of his albums, Shooting at the moon (1970) and Yes we have no more mananas (1976), both of which I enjoyed and played quite often, but sort of forgot later. When I went from tapes to vinyl in the 1990s I eventually picked up the Yes we have.. album (Harvest / EMI SHSP 4057) for NOK 150 and The Confessions of Dr. Dream and Other Stories (1974, Island ILPS 9263) for 100. Good used vinyl was cheaper than today. I bought many used LPs, and again, Ayers was sort of forgotten.

This has changed for the last weeks. The Dr Dream sequence, with Nico on vocals, is still very dense, chilling, and top quality – this is a good and underrated LP (did they listen not just to side A but side B also, at Allmusic.com, which gives it only two stars?) It has a very strong message to counter culture, be vary of dream makers, Dr. Dream and his ilk. Although the album arrived a bit late, and was not much heeded. This was prog after prog had fallen out of fashion.

The cover of The Confessions of Dr. Dream and Other Stories, scanned from my LP, below.

The cover has a man and a woman holding up masks to each other. The main sequence is complex music, not easy listening. The idea is that we are not really real to each other, in today’s society.

As I said, Ayers has been heavily played over the last weeks, and emerges as a much more interesting figure than I first thought. Listening to Unfairground (2007) in a digital version, I like the “prog” attitude which is still there in his songs. I hope it does not die out. On this album he emerges as older, more mature, still witty and observant, still with melancholy, but also more depressed than the 1970 man.

The way I see it, this depression is not psychological, mainly, but sociological. It happened to Ayers and a lot of other progressive artists from the 1965-75 period. It happened to the conscious part of the “1968 generation” generally. “What happened to our dream?” is a symbolic question.

Neil Young sings: “We were gonna save the world, then the weather changed, and it fell apart, and it breaks my heart” (“Walk like a giant”, on Psychedelic Pill 2012). “But think how close we came”.

Basically, the revolution that the “counter-culture” wanted did not happen. It was beaten down in the streets of Chicago during the Democratic convention in 1968, and in Paris and Prague the same year. “There’s blood in the streets of Chicago”, Jim Morrisson sang (“Peace frog”, Morrisson Hotel 1970); George R.R. Martin described it in his novel The Armageddon Rag.

Repression was the order of the day, here in the UK:

This picture could be called, “Long-haired freak brought back to normal”, or similar (although these terms are somewhat later). Note how one needed many men to do it. Ayers grew up with this kind of repression in his formative years as a youngster and young artist. The above picture is from a photo, probably ca 1968, shown in interview with Ayers: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a6kslKx5Zdo. This kind of repression, in the police as well as in schools, has recently also been documented in autobiographies from the time, including those of John Peel and Keith Richards, and in Miles, Barry 2004: Zappa – a biography.

Below, a 1972 concert picture http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wsF-gTyXA5Q

One should not be misled by appearances. There is a wordly look and a bit of a sneering attitude, not towards the audience, but in his music and the way he introduces it, “insouicance” towards the powers that be, for example, in the early videos of “Why are we sleeping” – a protest song (see also BBC version).

Another thing I like about him is that he has a kind of doodling attitude, rambling, being a bit lost, finding new ways. There is something wonderfully fresh and inventive, even if things don’t always work out in all his songs. An innovative aspect that can at times be thrilling, like when I first the best songs like “Walk on water” on the 2007 Unfairground. Just one word – wow.

He was certainly a paradox. From this thin young man one might expect a falsetto, but instead what comes out is a deep and somewhat world-weary voice. His words have a sense for small inconsequential things, but a special flair, in the direction of Syd Barrett, of making these small things suddenly emerge, flare up, with another and larger meaning. Truly a “prog” artistic ambition, if there ever was one. Yet at the same time Ayers scaled down and very consciously so, not wanting to be a superstar, but instead creating lyrics that were everyday and simple but also ironic and disobedient to the music machine as well as the rest of capitalism, or the system. He never obligated to become a money making artist, since he had seen other young artists like Jimi Hendrix being misused by the music machine. So even his most famous song May I is a bit “crossed over” so not to fit the hit machine either in France or the UK, although borrowing elements from both musical traditions, and free from commercial obligations, all the more playfully so,

Kevin Ayers was a musical innovator, a collage maker, a kind of “head” musical journalist (often, going down, down below, to the small things) – and thereby a postmodernist long before his time. He early rejected the technical-musical direction of Soft Machine and went for a more laid-back approach instead, at least on the surface. Yet some of his music is very intense, and has great complexity and depth.

He seems to have been a kind and charming but also sometimes shy and troubled man. The general idea in the 1970ies was that he lived the life and partied with long stays in Ibiza, and elsewhere , although he delivered an album a year or so for a long period, so he clearly worked with his music.

“A pretty face will find a place, it is an easy place to be”, he sings in “Walk on Water”, 2007.

“But you know

You’re only a show

And you’ll reap what you sow

In your own way”

This song targets three figures, the rich or successful who “just got it made” and “never see themselves completely”, the people who “really need attention” and “just see what they wanna see”, as well as the pretty faces.

As part of the counter-culture, Ayer’s target of critique was not capitalism as such but a wider category, “the establishment”. Music should be a kind of critical reportage about “the establishment” versus “the people”. The latter was a very vague category – flower power? Good vibrations? Love? – and softly defined (like Soft machine), not hardcoded like it became in the Marxist (or religious, ecological, feminist etc) 1970s splinter versions of counter-culture.

Ayers was a very conscious participant of the counter culture, as he said later, this was the first time a young generation had got up and questioned the whole system, “saying, we really won’t do, you know, what our parents did”. See interview (not dated, early 2000s?) here:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a6kslKx5Zdo

Kevin Ayers is presently rated as 42 percent gay on the gay-o-meter presented here http://www.gay-or-straight.com/Kevin%20Ayers. His 1970 counter culture persona is not so easy to place, with post-modern-gendered eyes.

Note the symbolism of the UK police picture, above. Three short haired men in helmets are attacking a long haired man. Down! Obey authority! This was the attitude of the establishment, as people experienced it at the time, making even Keith Richards (in Life) become very clear – the system was out to get us!

Finally, a shot of Kevin Ayers, in the 2000s interview referenced above. He is a good interview object, telling stories with laughter, morale and insights, speaking of the great turmoil of 1968, the dreams he carried, and what happened after.

His most famous song “May I” tells the story of a male traveler who, weary, looks for a place to eat and sit down. He finds a place. There, a woman is sitting by another table. In the song, he asks for her allowance to let him look at her, “for awhile”. This temporary sense is the clue to the song’s uplifting quality. He is not out to grab her or make love to her, but just look, for a little while.

“May I” is a bit like a fifteen minute visual coffee flirt – but also a still life picture, beautifully developed into words and melody. Words and music hang together, in all his work, despite the large musical variation, showing his awareness to another main message from the counter culture. The head is not dead.

It is typical of Ayers’ music that after a heavy attack there is some rest, peace and silence. This was the way “concept” albums were made, in those days. After the Dr. Dream sequence, we get the song “Two goes into four”, a reflective and dialectical Ayers:

“Two times no more

Two will make four

Blue goes into green

Mostly unseen

Blue becomes green

Dreams take me so far

Life is the star

Trapped in my jar

Go follow the wind

Open your heart

Then you may start

To make it better”

The last two lines are a direct quote from Beatles “Hey Jude”. In a 1998 interview, he describes his way into the middle-class Canterbury scene as just an amateur being chosen “because I had the longest hair”. He was “dancing in the dark” musically. At the same time he did not like the “self-indulgent” musical direction of Soft Machine, although they remained friends. The main philosopher who has made any sense to him, he sais, is Gurdieff,

“What he said made sense to me. What I really liked about him was, he was a total charlatan. He didn’t make any bones about it. His thing was that you cannot present the truth to people in simple form. You have to elaborate. Otherwise they’re not interested. Did you ever read his book? It’s just bullshit, absolute bullshit. But he says, you have to write 100 pages to say one sentence, to make it interesting for people. Otherwise they won’t accept it as real. You have to say a lot in order to get a little across.

Q: Are you still inspired by things like that when you write?

KA: It’s still there. I mean, I still think he was absolutely right. His two premises were, you have to say a lot to get a little across. you have to excite people. The other thing was, we’re only working at five percent of our potential, which made total sense.”

My comment – well – if not “total” sense (the kind of obscure head / hippie talk that did not help), at least a lot of sense. The cultural “elaboration” associated with the counter culture was what created a mass movement, not just a small movement or sect. However the glue that held it together was very much relying of the spirit of the time, 1968, “the age of aquarius”, a fully new way to live, and so on, that did not make it.

Later the interviewer asks:

“Q: You’re talking about hitting thirty- were you conscious of the British underground that had started around ’67 losing momentum around that time?

KA: You only become conscious of things that you have things to compare them to. You can’t make assessments if you don’t have something to compare them to. I think that what happened with post-war society–suddenly young people were going, we don’t like what our parents are doing. We don’t like war. The war was over, people had money, and they had time. It was like a one-off. My youngest daughter says to me, geez dad, I wish I’d lived in the sixties. I know what she means, because there was a whole bunch of stuff happening. People were pre-video and people read books in those days, and talked to each other. It was a unique time. In fact, if you check the history of human beings, you’ll find it’s the only time that young people ever got up and had any effect at all. What happened was that the establishment moved in and discredited them- “they’re hippies, they don’t wash, they smoke pot.” But there were huge advances in human rights and basic freedoms. It never happened in the history of man, never.”

A sociological part of the 1968 generation late-life depression is, very simply, that if you connect your hopes in your youth very strongly to the new and the young, there is a risk of misalignment later in life, especially if these hopes do not come true later on. As you turn old, you will not only feel out of it, but especially out of it, since the reason you were in was so associated with your youth in the first place. In Ayers’ words (2008 interview),

“I’m not getting any younger and it hits you after a certain age. What I mean is that you realize that certain thing probably won’t happen any more. There’s a kind of loss feeling more than anything else.”

Later in this interview he says that his albums have mainly been inspired by love affairs. “ I don’t necessarily have to write about the love affair but it just gives you the impetus to get going.” He also said, in a circa 2009 interview: “It’s true my attitude doesn’t suit the industry. I’m not into fame or ego. I’m crap at anything other than my music. There should be room for people like me.” An interesting thing about Ayers, like Sapho, is that you can seldom tell what is the gender of the person he loves, from the song itself. The love goes beyond gender. So perhaps he was a bit bi or gay. It does not matter.

Other sources: