One of the reasons why the 1960s can be classified as “optimistic” was that they had a clear topic in mind – “consumer society”, and what to do about it. Change seemed possible. Later, the topic turned into “capitalism”. This short essay tells why this was not a good idea.

Consumer society – back to the 60s future?

I read science fiction novels from the 1960s since I love their optimistic vision off the future, before all the bleakness and depression set in. Like I love the best music from that period. I listen to music referencing and critically reflecting the optimistic period, later, like A perfect circle: Motive (LP cover extract above).

Back then, from 1964-65 onwards, western culture was influenced by what was known as the youth revolt, commonly displayed by long-haired boys that challenged conventional gender norms by “looking like girls”. The youth revolt evolving into the counter culture had one main target, or obstacle – not yet defined fully as “enemy” – namely, consumer society. Later, by 1969, due to the repression of the youth revolt, a new image became dominant – there was an enemy, and its name was capitalism. Or the establishment. At the time, this was seen as a more “advanced” and mature analysis of society – the flower children finally growing up.

Was it – really? It is consumer society, not capitalism as such, that has contributed most to the current climate crisis. Doing away with capitalism has not lead to better climate performance (sometimes, the opposite, e g in the Soviet Union). The same production-consumption oriented economy has ruled society, regardless of political color and formal positions of power-holders. The “vague” and “fuzzy” consumer society analysis actually has grown less old, than the supposedly improved capitalism versions.

Back in the 1960s, as a young reader, I absorbed Aldous Huxley’s Brave new world, where citizens are indoctrinated into consuming, as well as novels by Philip K Dick and others detailing the problems of consumer society. Here is one of several 60ies novels where the traditional male role in consumer society was challenged:

Today, I think consumer society oriented analysis has stood the test of time better than most capitalism analyses. Although they may be combined, and consumer society analysis is somewhat blind unless it also has a map of core capital formations and political and economic processes. Its main point, to me, is that it includes all and any in the diagnoses. It does not creep down to the level of “us” versus “them”. Like working class and capitalists. Or one ethnic group against other groups.

Consumer society analysis basically says, this is complex, we are all into it, one or the other, in different roles and positions. Research may find “classes” of consumer pushers, dealers, strong and less strong consumer adherence / addiction, and so on, but this is clearly a varied landscape, not like a class division. And what is more, it is clearly related or broadly relational, meaning that the choices of one individual are clearly influenced by those of others. It is partly collective and partly individual behavior. It is partly economic but cultural, social and psychological (etc) also – clearly interdisciplinary.

Consumer society theory, appearing from the 1950s onwards, was tuned to the economic, social and cultural contribution of the individual, including the possibility of change on that level – not just the positioning between classes within the consumption cycle. Later research on life forms, work and family, and similar topics confirmed the perspective. Briefly put, consumer society is not just an ordering of society, but also of ways of life. The role of the male breadwinner has been one primary social “driver” behind the system, although women contribute too.

Marx, already, recognized that capitalism affects this syndrome at various levels – in more or less “civil” forms – where “relative” surplus value, developing from more “absolute” value forms, could emerge. Relative surplus value production became tuned to the superior position of the male breadwinner – even though it was actually women (and children), not men, who were the main workers in the early capitalist industry that Marx witnessed. Capitalism “absorbed” and “redirected” earlier societal gender arrangements, and added discrimination forms on its own. Women were the first main workers in the early industrial revolution, later replaced by men. When the “Russian proletariat” stood up in favour of the Russian revolution, e g in Petersburg, a majority of factory workers were still women – not men. It was only gradually that “industry” became a male bastion, and”consumption” a female affair, in the development of consumer society – with the US as leading force in the 20th century.

Jorun Solheim: Shakespeare i smuget, John Grieg forlag.

Anmeldt av Øystein Gullvåg Holter, oktober 2020

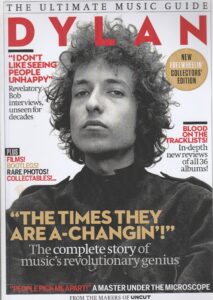

Jeg tenkte først: dette blir spennende. Så merket jeg, jeg la boka bort. Dette blir for heftig, tenkte jeg. La meg vente til jeg er på hytta, og har tid, fred og ro. I mellomtiden leste jeg meg litt opp. Bare litt. Jeg leste Uncut’s «Ultimate music guide: Dylan», som iallfall er fri for annonser, og gir oppdaterte syn på hva Mr Bob har prestert her i verden, album for album.

Solheim har levert en glitrende beskrivelse av hvordan Bob Dylans kunst, og særlig hans tekster, kan oppleves. Jeg bruker ordet «glitrende» fordi jeg ble grepet, da jeg først kom inn i boka, etter et kapittel eller to. Jeg leste i flere timer, og leste resten neste dag. Kunne ikke legge den vekk.

Og jeg har tenkt på den mye etterpå. Når jeg gjør praktisk arbeid. Noen av Dylans melodilinjer dukker opp i hodet mitt. Jeg husker tekstene som Solheim skriver om fra gammelt av, nynner sangene inni meg, og tolker dem nå på delvis nye måter. Hva mer kan man be om? Det holdt til å beise hele verandaen på hytta i dag. Indre melodier, musikk til arbeidet.

Jeg tenker også på hvordan forfatteren får fram det beste og viktigste i Dylans tekster. Hvordan hun balanserer kunst og resepsjon. Sine egne erfaringer, en personlig ramme fra ungdomstidas møte med Dylan i hans klassiske periode på 60-tallet, uten at dette tar overhånd, men danner en fin ramme om musikken som beskrives.

Det er sjelden jeg opplever en bok om musikk på denne måten. Jeg har lest en god del, selv om mye Dylan-litteratur (et stor felt, nå) er ukjent for meg. Jeg har hørt mye Dylan, gjennom tidene, og regner med at det også er en kvalifikasjon. Jeg har mitt eget personlige forhold, og et stort pluss ved Solheims bok er at hun gir stort rom for dette. Hun er åpen og ærlig og hva hun liker og misliker av hans musikk, og begrunner hvorfor dette er store kunstverk nettopp fordi kunstneren lar oss tolke på vår egen måte. Det er ingen fasit.

Forfatteren er litt eldre enn meg, og alder var faktisk viktig på en nokså spesiell måte, på 1960-tallet. De eldre hørte Dylan som et tilskudd til folk og protestsang, mens de yngre syntes det ble ennå bedre da han gikk forbi dette. Og plugget inn en elektrisk gitar. Solheim og jeg har imidlertid omtrent samme syn på dette. Det begynte med den symbolske vendingen i Dylans sanger. Så kom elektrifiseringen. Dette er vel i og for seg nokså allment godkjent nå – Dylans «klassiske» periode var fra da han startet å skrive sine egne mer «introverte» sanger, og etterhvert tok i bruk rock og el-instrumenter, fram til han måtte ta en tur på landet, det ble for heftig (for å si det enkelt), på slutten av 60-tallet. Med sanger som Hard rain’s gonna fall, Ballad of a thin man, Mr Tambourine man, Like a rolling stone. Solheim bruker mikroskopet omtrent som jeg ville gjort, på de store verkene fra denne tida, som Visions of Johanna.

En «glitrende» bok er ikke bare en bok man er enig i, men noe man har fått å være uenig i, noe man kan bryne seg på. La meg ta noen småsaker først.

Solheim avviser the Byrds versjon av Mr Tambourine man som sentimental. Var den egentlig det? Er ikke ordet kommersiell mer dekkende? Jeg hører ikke så mye sentimentalitet, men derimot et sterkt ønske om å lage noe som var «fengende», en ekte hit-låt. Som den ble. Som solgte langt utover det som hittil hadde vært Dylans fan-skare. Var det dårlig? Byrds ble da vitterlig etter hvert ganske gode Dylan-tolkere (Chimes of freedom f eks) og utviklet seg til et særdeles godt band (hvis i tvil, hør deres live versjon av 8 miles high, på live-albumet «the Byrds»). Så ja, litt mer balanse her, hadde vært kjekt.

I det hele tatt kunne jeg ha ønsket mer referanse til andre artister som utvekslet ideer og noter med hverandre, og litt mindre følelse av at Mr Bob var totalt i en «klasse for seg», King of the hill. Det var han ikke. Det var mange andre would-be-poeter (f eks John Lennon, Jim Morrison), og Dylan var som en svamp, tok til seg alt som var brukbart, fra disse (altså, ikke bare fra americana-røttene som han senere har framhevet). I forhold til Beatles, for eksempel – dette var toveis innflytelse, på midten av 60-tallet.

Solheim skriver et sted at hun forteller mest om tekstene til Dylan fordi hun skriver en bok. Det er ikke en helt god begrunnelse – og heller ikke hovedbegrunnelsen i boka – som er at hun skriver om det hun ble mest opptatt av. Men jeg skjønner hva hun mener. Det er lettere å forholde seg mest til tekstene i en bok, på samme måte som musikken er hovedemnet, på et noteark.

Det er ikke slik at forfatteren bare ser på Dylans tekster og ikke hører på melodiene og musikken. Hun framhever stemmen, hvordan den enten gjorde sterkt inntrykk, eller ble avvist. Solheims små anekdoter fra Dylan-mottakelsen på 60-tallet treffer blink. Jeg opplevde selv hvordan min mor ba meg skru ned lyden på Dylan’s Hard rain, ut fra at hun ikke «orket mer av den stemmen», på 60-tallet. Og jeg husker samme diskusjon på fester. Boka er full av slike treffende referanser til 60-tallets kulturendringer. Det fikk være grenser! Dette var i en periode der langt hår for gutter fortsatt var kontroversielt. Der lytting til Bob Dylan fikk preg av å være «motkultur», et brudd med den herskende kulturen, systemet, eller «the establishment» som det etter hvert ble kalt.

Likevel savner jeg litt mer om musikken og melodiene. Melodiene, særlig. Solheim kunne godt vært tydeligere på å framheve melodienes betydning, når det kommer til «I want you», for eksempel, som har en av Dylans mest fengende melodier. Kunstverket er en enhet (mer eller mindre vellykket) av tekst / sang, og melodi / musikk. Ordene i I want you er for meg tegn på glede, yrhet, ikke bare en stabel av fenomener eller metaforer – når man hører dem som sang, med musikken. Går man bare inn i teksten, og leser ham som poet, blir det for trangt. Om man hører ordene sammen med melodien, gir de en annen – eller la oss si, tredje – mening. De betyr noe nytt sammen. Solheim skriver stort sett bra om dette, boka er ikke en løsrevet «tekstlig» poesianalyse, selv om jeg altså gjerne hadde sett mer om musikken og melodiene.

Dette kan ha å gjøre med at jeg selv var aktiv i kritikken av kommersiell musikk på slutten av 60-tallet, og var med på å grunnlegge organisasjonen Samspill i 1971, som senere la grunnlag for plateselskapet Mai, og en musikkavis, Vår musikk. Vi var motstandere av ensidig kommersialisering av musikken, men samtidig tilhengere av utbredt konsum (av god musikk). En umulig oppgave? Javisst. Tanken var at motkulturen kunne utnytte kommersielle krefter (ikke bare omvendt). Det betydde, for eksempel, at tilmed Paul McCartney kunne skrive en «god nok» tekst, fordi det som teller, er det totale uttrykket, kunstverket slik det faktisk kommer i bruk, ikke bare teksten for seg. Når man tar inn at Byrds’ versjon av Tambourine man vekket gjenklang i tusener av amerikanske hjem der Dylan direkte ikke hadde fungert, blir vurderingen annerledes. Dylan ble selv opptatt av å bidra til samfunnskritisk pop. Forfatteren virker mindre interessert.

Fra en kjønnsforsker som Solheim hadde jeg kanskje ventet en ennå vassere diagnose av Dylan som proto-feminist, «androgynatisk» (for å bruke et begrep for boka Menns livssammenheng), til tider trans, en banebryter i forhold til kjønn. Her har forfatteren mye spennende å si, men ambisjonsnivået er trolig klokelig lagt noen hakk ned. Hun dokumenterer at Dylan var kvinnevennlig og relasjonell i bred forstand og ikke bare kan avvises som mannssentrert eller (av og til) misogynistisk, men hun går ikke så mye videre fra dette. Det tror jeg er realistisk. Det er kanskje riktig at Dylan på sitt beste kan tolkes som forkjemper for en ny kjønnsorden – men vi er fortsatt innen en mannssentrert kultur. Emnet fortjener oppfølging.

Det som blir tydelig, er at Solheim, ved å ha med kjønnsperspektivet i analysen, ofte tolker tekstene på en ny måte. Dette er kanskje bokas viktigste «added value» i forhold til den eksisterende litteraturen om Dylan, som stort sett er skrevet av menn.

Solheim avslutter boka med et drømmekapittel. Dylan kommer ramlende inn i buskaset mens forfatteren sitter under et tre og leser en bok. De prater og samtalen består utelukkende av sitater fra Dylan-sanger. Godt levert. Men jeg blir litt undrende, når forfatteren ender kvelden med å bre over gjesten et teppe, og så gå å legge seg, alene. Mange hadde nok hatt en litt våtere drøm.

Et par videre utfordringer kan nevnes. Det er litt tendens i boka til å teoretisere seg bort fra hovedsakene – men ikke mye. De antropologiske referansene er relevante (og dempet ned) – bra – men hvor mye de egentlig bidrar med, i forhold til Dylans tekster, er ikke alltid klart. Metaforene er bestemte og konkrete – javel – men så kan de også bety forskjellige ting – javel. Som nevnt, dette er ikke tekster, det er del av et kunstverk som kalles «låt», «sang», «track» osv – og analyse derfra kan trolig gi mer mening i bildet.

Boka er personlig vinklet – til en viss grad. En antropolog oppsøker sitt personlige felt. Hvordan er denne grensen dratt? Gjentar forfatteren det hun har opplevd som hovedsaken, ved artisten? Blir hun selv en «masked marauder»? Er boka litt mystisk?

Jeg synes den forblir litt uavklart, uten en klar slutt (men ikke mystisk). Uavklart for eksempel fordi forfatteren sier nokså lite om hva som fikk henne til å digge Dylan i ungdommen ut fra sin egen familiesituasjon, eller hva som gjorde at hun sluttet å lytte, senere. Det ligger i bakgrunnen men spesifiseres ikke. Her og nå, i denne boka, er dette kanskje akkurat passe. Det er Dylan, ikke Solheim, som er i fokus. Det er godt levert og balansert.

Boka river ned myter om 60-tallet – og slutten er et godt eksempel. Forfatteren legger et teppe over gjesten i stolen. Ikke en natt i felles seng. Hvorfor tenkte jeg først, at dette var litt spakt? Burde hun ikke hatt en «våt drøm»? Jeg tror jeg tenkte ut fra fordommer om 60-tallet, som virker inn på de fleste av oss – at det den gang mest handlet om «sex drugs and rock’n’roll». Men Dylan var ikke et sexsymbol. Han var «hode», i motkulturen. En motkultur som handlet om samfunnsendring, ikke sex drugs eller rocknroll. Ikke først og fremst iallfall, selv om det kom som motvekter etterhvert. Solheim får dette fint fram, gjennom sin poetiske og symbolske tolkning av Dylan.

Alt i alt er denne boka en fin leseropplevelse som virker inn på leseren på mange plan, og som dermed er verdig adjektivet «glitrende». Dette er den beste boka om musikk jeg har lest på lenge. Den anbefales ikke bare ut fra interesse for Bob Dylan, men ut fra interesse for motkultur, ungdomsopprør og kjønn og likestilling.

Etter å ha lest Solheim, kikket jeg litt mer på Uncuts guide til Dylan. Jeg oppdaget ikke bare at 2 av 2 redaktører er menn, men også at 18 av 18 bidragsytere er menn (s 5). Tenk det, Hedda! Er det mulig!? Første gang en kvinne nevnes, er det under «Thanks to». Denne sterke mannsdominansen i Dylan-tradisjonen er interessant, og kanskje noe Solheim – og andre – kan komme tilbake til.

You might think, at the root of Heavy Rock lies power and chauvinism. Misogyny and male supremacy. Judging from some excess trends in heavy rock, later. With lyrics like “the soul of a woman was created below” (gleefully sung – though not written – by Led Zeppelin on “Dazed and confused”).

The truth is different. At the core of heavy was a mellow part. Even a feminine part, and sometimes a feminist perspective. This was in the early days of heavy rock, what we might call the “proto” stage of heavy. A this time, it was a tendency in rock, not yet a separate genre. Rock music was the key part of a counter culture which was still quite cohesive, not yet split up into music genres, different politics, or beliefs. Basically it united everyone under their long hair. Young men as well as women. It was OK for men to display more feminine traits, like expressing feelings and growing their hair long, like women. It was a case of the young and the new, against the old. With long hair and rock music as main symbols of the new. This was soon ridiculed for being childish and naive (a debatable point, compared to the more politicized counter culture later), and is important to understand, for why “mellow” came into the heart of “heavy”.

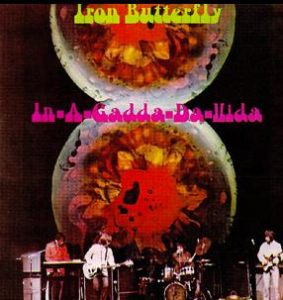

This mellow core of heavy is very evident on one of the first early heavy rock albums, Iron Butterfly: Heavy. Released in January 1968, before the debut albums of Deep Purple (July 1968), Led Zeppelin (1969), and Black Sabbath (1970) – the giants that later defined the heavy rock field. Things changed fast in those days, and before Iron Butterfly, what mainly existed was the “noise rock” of Cream and other blues-rockers. “Heavy” made heavy rock into a more distinct part of rock music, even if it was only in “proto” form, not fully realized.

The seminal Heavy album starts with two songs that criticize current society. One is about possession and property. The other is about going beyond that paradigm, going “beyond conscious power”.

So in fact the world’s first heavy rock album starts with a critique of the sense of possession, in love life, with these lines:

“When a man has a woman

And he doesn’t really love her

Why does he burn inside

When she starts to love another?

It’s possession

It’s possession

It’s possession

It’s possession”

The song isn’t just about possession in general, but about men’s feeling of possession, or in a more recent term, men’s feeling of “entitlement”. Even if the man does not really love the woman, he cannot take the rejection from her, and that she gives her love to another man.

Instead, he burns inside.

Why? It’s possession. The song refrain resembles a chant, a drone. Like a message burned in, through heavy chords and threatening music.

So, starting from the number one song on the first heavy album, we find a critique of masculinity and possessiveness. Associating men, property and fake love.

The album was recorded in autumn 1967, in the context of the turbulent and hopeful youth revolt of 1966-67, before the year of struggle and defeat, 1968. Youth were waking up everywhere. The proportion of long-haired among young men rose exponentially. Non-violent change methods were tried out on a large scale (like sit-ins, street theater, new forms of art, new economies). It looked like the authorities could accept the changes. “Socialism with a human face” was rising in Checkoslovakia.

You need a calendar to interpret these and other rock classics from the period, since the mood changed fast. 1966-67 was quite different from what came later. This is well brought out in John Savage’s book “1966” (Faber and Faber, London 2015).

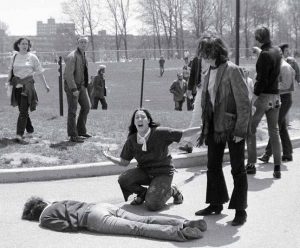

1968 was different and in many ways a shock. First, the counter culture / new left was defeated through street battles in Paris in May 1968. Then, in August, the Soviet Union invaded Checkoslovakia and squashed the new left-liberal democracy. The setback occured in the US and other countries too, in different forms, with the murders at Kent University in 1970 as the most symbolic event in the US.

Different rock bands and artists developed different responses to these events. What is common is a change of mood, due to the defeat. Some bands, like Steppenwolf, developed more political lyrics, like the critique of US capitalism on the album Monster (1970), and feminist lyrics also (e.g. For ladies only, 1971). Jefferson Airplane’s Volunteers (1969) was still vaguely hopeful, and similarly “revolutionary” in its view of society (with lyrics like “throw down the walls”).

For interpreting rock music classic albums, having a calendar or a diary at hand is a must. Even better, with in-depth music histories, like the Savage book.

Compared to groups like Steppenwolf, Iron Butterfly’s lyrics were less overtly political, keeping to the early counter culture message of going beyond ordinary politics (since this was associated with the establishment and the adult world). The music at the time reflected split opinions and diverse experiences in the counter culture, with some parts drifting towards more militant, adult and (traditionally) political response. Again, arguably, with very mixed results, or indeed rather bad results, even if the former youth revolt ideas were somewhat childish (e g Pink Floyd, with child-voices: “Why can’t we play today”. Why can’t our dream just become true).

Political and feminist lyrics, in the songs of Iron Butterfly, were more like an undercurrent. They speak like “heads”, in these songs. On this – maybe naive and childish – level, the song “Possession” spells out the problem, or a main part of it. The next song, “Unconscious power” points to the solution.

(The cover shows keyboard and singer Doug Ingle, main composer and writer, somewhat alone – on the other side of the great monumental ear in the middle)

(The cover shows keyboard and singer Doug Ingle, main composer and writer, somewhat alone – on the other side of the great monumental ear in the middle)

“We all want to prepare you

The unbelievable is going to happen

It will linger in your mind forever

Let this carry you wherever, wherever

Triggering the unconscious power

Removing all your inhibitions

Releasing complete freedom of thought

Sensations of every sense will prepare

With this you will see every thing

Triggering the unconscious power

Triggering the unconscious power

I say to you nothin’ for now

For now we know all

We know all

We know all

We know all”

The lyric is very optimistic, something unbelievable will happen. It strikes the tone of late 1960s optimism. And the change will be large, it will linger forever. You should let this knowledge carry you, wherever. Triggering your unconscious power.

Sounds superficial? Well, it was before “new age” ideologies. Here are young long-haired men trying to psychoanalyze the world. Very limited, it may be said. In fact this was often said, at the time also, about the “childish” and “simple” aspect of the youth revolt and early counter culture. It was basically naïve. Some counter culture artists like Frank Zappa contributed to this idea. Hippies were all fake.

But note what these two songs are doing.

First, they are musically far from hippie territory. There is a feeling of anxiety and even terror, not a cozy “summer of love”, in the music (a worthy runner up is Blue Oyster Cult: This ain’t the summer of love, on the album Agents of fortune, 1976).

There is the typical impatience of the late 60ies – go right to the core. Just play, even if you don’t know how to do it.

They dig into a feeling, a burning inside, something many people recognize, not least, men. They start with a widespread experience, a phenomenon. They describe it vividly, like the pop art emerging at the time. It’s concise. They don’t make extra words, or opinions. They just jump right into the explanation. This burning has to do with possession and property. They describe men’s sexual jealousy and sense of property as a disease, even if they don’t use that term.

It was certainly enough to make long haired parts of the youth of middle-class America and elsewhere wake up, even if it did not make a hit. The band sold millions soon after, with the album “In a gadda da vida” (1968). Many Iron Butterfly songs are harsh condemnations of an oppressive society. “In a gadda…”, as a contrast, had a positive message, pointing to a better future. It caught the imagination of young people in the US, becoming a marker of youth culture influence.

This ability to catch “surface” phenomena, and (to some extent) point to better solutions, was a main reason why youth and counter culture movement expanded rapidly from the mid 1960s onwards. Like using the long hair to go beyond traditional political divides. The tendency was leftish, but this was to be the “new” left, not the old. Within the youth movement, 1964-67, the main target of critique was very broad, it was the adult world, fake family life and consumer society (Frank Zappa: “plastic people”), rather than a specific (adult) political target like capitalism or class. Gender was also mainly implicit, even if the young men growing their hair longer were soon ridiculed for “looking like girls”. The underlying feminine / feminist current of the 1960s changes has not been sufficiently studied.

So why does Iron Butterfly close their “Unconscious power” song by saying “I say to you nothin’ for now”? And repeating this point? This can be interpreted as “headspeak”.

The notion of the “head” was important in the counter culture. Heads were thinking people or intellectuals guiding the movement, but they should not become a new upper class. So for a head to withdraw, and say, I say nothing for now (since we are right at the beginning), could be the right thing to do. Very cool. Rather than preaching or predicting. The message in the song is very clear: you can see for yourself. “We know all”. If only we let in our “unconscious power”.

A major counter-argument, to what has been said before, is that Iron Butterfly’s “Heavy” album does not really represent the birth of heavy rock. For this, one should listen to albums like the first Black Sabbath album, instead.

This is true on one level. The “heavy” sonic signature is more recognizable here, than on Iron Butterfly’s Heavy. Black Sabbath goes in the direction of “doom and gloom” – towards heavy metal, and dark metal, the notable 1970s trends. On the other hand, they also lean backwards on the blues of “noise rockers” like Cream. Not very inventive, compared to the best Iron Butterfly melody lines, although more distinctive and genre-defining. Bands like Procol Harum also picked up some of the doom and gloom trend, although they cannot be classified as founders of heavy rock.

However, even if Black Sabbath was maybe the first to trademark an “evolved” heavy sound, other bands evolved in other ways, and the “first” position can be questioned. If we allow the scope of “proto” heavy, the roots of the genre, Iron Butterfly’s first album stands strong.

For understanding the evolution of counter culture music, The Byrds is a useful case. Even if it did not evolve into heavy rock, but rather, early “Americana”, country and western influenced music.

The Byrds was a key link, making mid-60ies folk music into folk-rock-pop hits. They started out singing Bob Dylan’s songs, making a major hit with a pop-rock version of “Mr Tambourine man”, with several weeks at the top of the single sales lists. This was followed up by others, like “All I really want to do”, “My back pages”, and “Chimes of freedom”. However, the public gradually got tired of the somewhat stereotypical Byrds treatment of Dylan’s songs, and sales dwindled. Still, they managed to get his main message across, as a foundation for further rock development. Dylan took up the challenge, one might say, with “Like a rolling stone”, and others. Dylan’s insights came to stay, in rock music development, partly thanks to the Byrds.

The Byrds took much of their material from Bob Dylan’s “Another side of Bob Dylan” album, 1964, in some ways his most revolutionary or radical album, still keeping to his “protest” roots.

Do you think the “mellow core” of heavy rock is only a special back-then case? Don’t be too sure. There is more “mellow stuff” lurking behind the hard, heavy and metal doom lyrics and headlines. This is the subject of another blog post, but two recent examples deserve mention.

Rammstein, on their recent (untitled) album (2019), sings about the abuses of German power through the times (Deutschland) and the violations in the name of religion (Zeigt dich). They are critical, but also mellow (Radio).

Opeth, on their last album “In cauda venenum” (2019), are similarly critical, with some doom and gloom as behoves the genre, but they are also mellow, for example in the track Dignity (Svekets prins), using a sample from prime minister Olof Palme’s new year speech, some years before he was murdered. Palme talks about the inner anxiety (uro) one feels, even if social democratic society seems to go well. Opeth – bless them – takes it on, from there. Here there be tygers.

Take as example – Iron Butterfly.

How strange, now, to listen to this American music, compared to today’s developments. How strange to hear so much relevant about today, even long before.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-3569220-1465510845-1921.jpeg.jpg)

Try “In the time of our lives”, “Filled with fear”, and “Real fright”. Check “Unconscious power” on their first album Heavy, and “Possession” (avoid the repeated-to-death “In a gadda da vida”).

These are songs from the counter culture, way back when. It did not win the agenda. Still, interesting listening. Sometimes even more relevant today.

Hippie music – not quite dead?

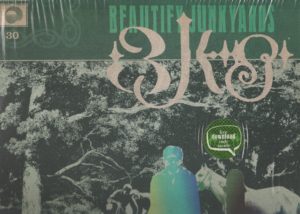

Checking out Beautify Junkyards: The invisible world of Beautify Junkyards. Ghost box records.

This is a Portuguese band, recorded in Lisbon. I came across it, searching for good new music, listened to it on Tidal, and then decided to buy the LP. Very glad I did.

First thing – the title “hippie music” is partly wrong. “Mystic music” is maybe a better word. This is a new kind of music, whatever its roots.

Yet it does have a lot of hippie and 1960s youth movement references. The music style is much like the band The United States of America, on their first album, the song Love letter for a dead Che. Che Guevara, that is. Women voices lamenting.

The band cites the poet William Butler Keats, much in the hippie fashion, if there is a “dim kingdom” beyond the ills of this earth, why not grab for it.. “There is more love there, than upon the earth”.

Someone named “major Tom” has been brought in, to produce this, and it has been done in intricate and engaging ways. Often, I feel, the music is best when it gets down to its Portuguese or even Brazilian roots, or moves in that direction. That’s when things really start to swing.

All in all a very good LP, recommended.

You might think a group named “Gentle Giant” was about masculinity. Maybe it was. But this group was mainly about “weird”, as in “far out”, beyond any of the confines of their context, the music scene in the UK around 1970. Where, suddenly, everyone and his son in law were competing, how to be “progressive”. How to push “prog” music along.

Gentle Giant were masters of this art. Pushing prog rock beyond the borders of convention, acceptance and imagination of the day, with very experimental albums – resulting in a “niche” limited following. Later, their merits have been rediscovered.

Now, excerpts of their first three albums have been re-mixed and reissued by Steven Wilson (Three piece suite). I bought this double LP. Cover reproduced below.

I have compared the original albums to the Wilson remix. I like the originals better, on most accounts. There, the production goes further into the “weird” territorry, along with the music. The ambience, especially, is more striking. But this is probably not so much due to Wilson, rather it is due to the state of the tapes he worked with. The tape recordings on my original LPs sound more fresh, with more treble energy. I bet that the tapes that Wilson worked with – after years of storage – were somewhat reduced in the high treble. This is what happens to tapes over time.

I find plusses and minuses across the line. If I want Gentle Giant to sound “modern and normal”, not so hard to accept, I turn on the Wilson mix. If I want them in all their weirdness, disregarding some glaring and badly composed production, I go back to the originals. If I had to choose one, the originals win out. But it is nice to have both.

A feminist pioneer belts it out:

Grace Slick: Manhole (1974)

Front side of the cover of my original LP (on Grunt label)

Grace Slick was an icon of the youth revolution in the late 1960s.

Was she only a pretty face? No.

If you want a direct ‘time window’ into the end of the hippie era, recorded in 1974, try this LP.

A very under-appreciated album.

Cover back side

“On Manhole, the music is wonderfully dense, macabre, exhilarating, and totally out there. This is a great portion of music from the lead singer of one of America’s great music groups. ” Joe Viglione, Allmusic cf https://www.allmusic.com/album/manhole-mw0000015080

When I listen now, 2019, I still think – like I did when first hearing the album in the 1970s – that Slick often leans too far towards “power” singing, becoming insistent, belting or shouting out her message. When she moderates her voice, things go better.

And yes, now as before, I think the arrangements and melodies sometimes become pompous.

Even so, this is a great album.

The feminist and progressive message is clear. For example, Slick is not singing about some up-above lover, willing to let his charms, like other female artists of the day, including Joni Mitchell (“the big man arrives”..). There is more fire-power here. She sings with the men she loves, instead. Remarkably, her duets with Paul Kantner are among the best material – and the Kantner songs are among the best on the LP.

Manhole has been under-appreciated and downgraded for too long. Even in a recent review, the tendency remains (see e g http://www.thevinyldistrict.com/storefront/2015/07/graded-on-a-curve-grace-slick-manhole/). The reviewer says that when she innovates, it is “obscure”. When she doesn’t, it is stale. Damned if you do; damned if you don’t.

I think she ran circles around most other female singers of her day – they often sound stale and meek, compared to this. Do I like the sound of her singing? I am mixed. Sometimes no. It is too much. Too masculine, even. But is it new? Yes. Is it assertive? Yes. Does it carry a message? Yes. Does it spell artistic freedom? Yes.

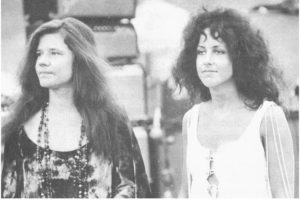

Women of the revolution: Janis Joplin and Grace Slick at Woodstock 1969

Manhole needs to be understood in context. It was made at the end of the Jefferson Airplane period, before the band changed into the more commercial and less progressive Jefferson Starship, in the mid-70ies.

Jon Viglione at All music guide describes it fairly well:

“Manhole was the last of the experimental Jefferson Airplane, and Grace Slick’s first official solo album. While Bark and Long John Silver, the final stages of the original Airplane, displayed the excessive psychedelic nature of the musicians within the confines of their group format, Blows Against the Empire, Sunfighter, and Baron Von Tollbooth and the Chrome Nun allowed for total artistic expression. Manhole concluded this phase with 1974’s other release, the Jefferson Starship’s Dragonfly.”

Bark and Long John Silver were rather unsuccessful attempts of the Airplane – after a string of successful innovative albums in the late 60ies, including After bathing at Baxter’s, Crown of creation, and Volunteers. The band realized this, and attempted new formats and groupings from the members of the band – like the spin-off Hot Tuna. The main “reformulation” of the band emerged in the string of LPs mentioned by Viglione – Blows against the empire, Sunfighter, and Baron von Toolboth.

Manhole pushed the concept a little further, until it collapsed. Quite symbolic.

Sometimes, when Grace sings on this album, I am reminded of Tom Jones or other singers when they – to my ears – are overdoing it. Sometimes I can understand why All music guide, despite applause from Viglione, gave it just three out of five stars. Other times, it works really well. Everyone – the guys in the band – are doing their thing. Grace just inserts her voice above them, steering them towards joy and artistic freedom.

The guys are not just the local pub band. David Crosby joins in the best singing on the album. Paul Kantner continues his explorations as lead voice on some of the songs, and contributes on the rest. Jack Casady plays some beautiful bass. Barbata is good on drums, as are many of the other players. When not drowned out by the voice.

All music guide fails to appreciate the string of albums ending with Manhole. It gives Sunfighter just three out of five stars, and Baron... just two. This is ridiculous. These are classic albums, despite their faults. Four to five stars.

Despite its faults, Manhole is a special album, a time window, a testament, and a future teller – today also.

Along the way, Kantner had led the show, now Slick led it.

English is not my native language, so maybe my use of “belt” or “belting” is not the correct term. I don’t want to undermine Grace Slick’s greatness as a singer. Turns out, it does not. On the contrary, learning how to belt, distinct from how to yell, may still make a rock star out of you. Belting, as a form of shouty singing, seems to go back to way back when, in human communication. With belting, you claim a territorry, sound-wise – this is more than the warning shouting or yelling of a tribe, and more than soft singing for the close group – in my interpretation. Compared to opera or classical singing, rock singers use belt voice as part of the repertoire. Growling and grunting can be seen as offshoots.

Variation is the key to Grace Slick as a singer, not just the belting part. The intensity of her voice, whatever the volume or singing style, is fabulously shown in the solo voice recording of White Rabbit – now available on the web:

Grace Slick’s Vocals On ‘White Rabbit’ Are Going Viral And They Will Give You Goosebumps

She did not have a “style” (which was a point, at the time) – this singing is just extremely forceful, climbing slowly towards belting, based on the melody and lyrics.

But arguably, the way she uses her voice is even more masterful on Manhole. “Look up! The roof is gone”, she sings. The old oppression is gone. There are new potentials, new possibilities.

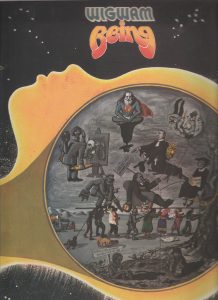

Det finske bandet Wigwam spilte inn Being i 1973. Det er vel omtrent så prog man kan komme, i nordisk prog i 1965-75-perioden. Being går tre ganger rundt det meste, både musikalsk og innholdsmessig. Er det vellykket? Tja, delvis, men det tar litt tid, litt lytting, før resepten «setter seg». Er det prog? Avgjort ja.

Noen kommentarer på nett: «Being” was WIGWAM’s 5th album and represents one of the most profound and highly dramatized concept albums mixing religious and political themes in a very strange little album.” Ja, very strange indeed, iallfall om man ikke forstår hva Wigwam prøver å uttrykke. «It’s my understanding that the album caused a bit of tension in the band, with some members having a problem with the extremely politicised lyrics. It’s not the words that irritate me, though, than the delivery.”

Flere kommentarer her: http://www.progarchives.com/album.asp?id=3435

Noen misliker vokalen – «particularly the vocals by Jukka Gustavson. ‘Being’ leaves me cold due to the unemotional content.” Men er det ufølsomt? Jeg vil heller si, en original og så å si «sosiologisk» vokal. Akkurat som sosiologien i barnets hode, på forsiden. En type Brecht fremmedgjøring, nesten, i måten vokalen er dubbet på, den stiger og synker atonalt. Like det eller ikke – det er originalt. Tilmed for Wigwam, som senere gikk tilbake til en mer glatt stil, med Jim Pembroke som vokalist.

En førstepress Wigwam Being LP fra Love Records koster nå ca 150 euro, eller mer, på Discogs, i Near Mint utgave. Re-utgaven jeg har, fra Svart Records, koster 70-80 euro. Man kan få en god del ut av Wigwam ved å kjøpe Rumours on the rebound, en dobbel samle-LP, som kan fås til 20-30 euro. Selv om det ikke er samme sak. Being, særlig, er verd et eget kjøp.

Kommentarer på Amazon: «Perhaps the most musically dark, complex and harmonically dense album Wigwam ever made(1973). As impressively challenging to the ear as any of the more serious works of Frank Zappa, Mahavishnu Orchestra or PFM, Yes, Gentle Giant etc. Not for the faint hearted.»

«Imagine a rock-pop group that has members that also like Soft Machine, Zappa and a bit of blues mixed with sophisticated jazz. Add some nice vocal harmonies, some a la Stevie Wonder(!), and weird lyrics (which are sang in a choppy kind-a-way!) and you’ve got a pretty original sound. I recommend you get “Fairy Port'” first. But then come to this which is great also!”

Choppy – ja, kanskje, men særlig, atonale toner.

Tekstene er kritiske – progge – og ikke vanskelig å forstå, iallfall ikke i en nordisk kontekst. Finland levde tett innpå Sovjet, i den kalde krigen. Frykten var stor for atomkrig – jfr Wigwam’s Nuclear nightclub LP, litt senere enn Being. Og The dark album.

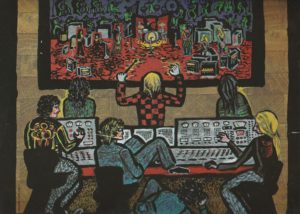

Omslaget, bildet i barnets hode, er laget omtrent som en karikatur fra tidlig moderne tid – øvrigheten på toppen, vanlige folk i midten, og avvikere nederst. Figurene på toppen er de viktigste figurene i sangene, blant annet kommunisten, presten og småborgeren. Kapitalisten holder et skilt med «US get into Vietnam Chile etc».

Under alle disse øvrighetspersonene ser vi en kø av «vanlige folk» som bærer byrdene under det hele. Nederst ser vi to figurer under et skilt «Subcultural bayarea», en mager mann og en fyllik. Køen av vanlige folk går mot en samling bygninger i bakgrunnen, på høyre side, med røyk fra skorsteiner, med et lysende reklameskilt «Pariah». Det minner litt om Auschwitz. Røyken blander seg med grenene fra kunnskapens tre, der akademikeren sitter og er bundet på den ene foten.

Dette er et av de heftigste politisk prog-omslagene som er laget. Er det «ekstremt politisk»? Nei, men det er fokusert på politikk. På toppen sitter en mann med skjegg og supermanndrakt med en P på trøya, og rød kappe. – Omslaget ble laget av Jukka Gustavson, (directions) og Jorma Auersalo (art work).

Presten (i Gustavsons Pride of the biosphere) forteller om voldtekt under krigen:

As I cast my mind back to the first years of war, to the best times

of my entire career as a chaplain, I am still filled with deep piety,

with profound gratitude and awe at the recollection of one remarkable,

rather remarcable, recurrent course of events that came to pass

and shed its light in my workaday life in those halcyon years.

Warfare is rough play, as we all know, and in the manly and mera-

less martial turmoil surely all of us, even the merest Negro, the

lowliest Japanese or Jew, are equals in the sight of the same

Gawd; indeed, I wish to emphasize this!-

Well, as I was saying, it is with intense emotion and profound

humility that I recall those months of May, days when the

first ripe cherries would be fresh off the bough; sitting; there

in the dull humdrum of the Officers’ Mess we would naturally

be pleasantly diverted by questions such as- would we like some cherries!

However, it became virtually a point of tradition, yes,, hearing

that innocent query rather more lusciously worded: a couple

of “Gerries”? How about some Gerries! At this, and blushing

almost openly, the officers would proceed to rape the waitresses

in full view and afterwards shoot them on the spot.

And so, as the afflicted blood of these possessed women crimsoned

the drab floor out our mess, my turn would come to step forth

and perform my own assignment in this Extraordinary, this quite

extraordinary, colorful drama! – Those fallen souls laid to

their last rest before the scorching pains of flaming hellfire,

we would fold our hands upon the familiar words of my esteemed

colleague – words that so frequently during my career have

intrigued me and brought me succor – inscrutable are the ways

of the Lord..and how can we mortals be expected to mind and

master every turn, a-men.

Det er ikke presten som snakker her. Det er en politisk karikatur av presten, akkurat som på omslaget. Figuren blir beskrevet omtrent som den gale generalen i Dr. Strangelove. Det samme gjelder kommunisten, som er avbildet på omslaget mens han skjærer almuen ned med en sigd. Kommunisten er også en parodi, eller Brechtiansk fremstilt, fremmedgjørende. Tatt ennå litt lenger ut, a la Zappa. De som blir “offended” av dette har ikke skjønt hva det handler om – eller, låta treffer litt for godt, en innertier.

InspiRed Machine, by Jukka Gustavson

Working men in all countries let us unite

in vengeance for the time has come to

annihilate the bourgeoisie and suck the

rest up now is the time when Commu-

nism will rule the world and red shall be

the one color suffered to wave let us

take up arms let us join forces com-

rades let us march let us conquer for

behind us comrades you have the most

powerful and advanced nation in the

world also the world’s most modern

least checked weapons and the Red

Army comrades towards peace and hap-

piness on Earth towards the most

ethical and natural state and system

in the world, comrades!!!

Det er bare i starten, i beskrivelsen av proletaren, første sang på plata, at ikke parodien ligger nær ved. Her er det også enkle linjer, men det er ikke en karikatur.

Proletarian, by Jukka Gustavson

Worn through by now, all spent..my pain

property, trickery; Political treasury, politics,

lush lies

Bitterness, repeating myself, impotence;

and the pink backs, suction-directed..us being breathed

into stupor; sucking

Scabbing. Scrathing..I’m punished –

The Mob ever drunker; comrades,

there always

And the leaders, the bosses, responsibility flags, salaries soar –

graftsmanship grows, competence decays

Altså – vanlige folk sliter. Vanlige folk får byrdene, av kranglingen mellom de store. Systemet utbytter vanlige folk. De rike skor seg. Proletaren prøver å advare, men mobben er fordrukken som alltid. Spillet blir hovedsaken. Kompetansen går tapt.

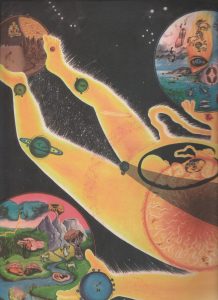

Hodet på omslaget er del av et barn, et foster – med mange muligheter, andre verdener, tegnet inn på baksiden. Selv om forholdene er nokså dystre i hodet, er det mange kroppslige og sanselige muligheter. Her er baksiden.

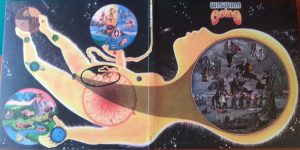

Her er helheten – omslaget brettet ut:

Selv om mye er dystert på Being, er musikken lys, delvis håpefull, ikke mørk. Det er fortsatt et glimt av hippielogikk, kjærlighet kan endre verden. Det følsomme barnet.

Min kritikk er ikke at skiva er dårlig, men heller at den er litt for hektisk, over-flink, til tider, og prøver litt for mye på en gang. Men vel, dermed ble den også en klassiker.

I have been reading Chris Beckett’s science fiction novel America city – a direct extrapolation from today’s events in the US. A hundred years from now, the south of the US is no longer liveable. Immigrants flow to the north. But to win the election, presidential candidate Slaymaker has to relieve the burden on the northern US states. His outspoken female (and partly feminist) advisor comes up with an advice: what about Canada, they have room for our refugees. With scary but quite probable results.

This book, together with the great conclusion of the Dark Eden trilogy, Daughter of Eden, makes Beckett my favorite current sci-fi author. There, he goes into the mind of a “ghostspeaker”, the kind of woman prophet-sayer that is otherwise not much credited in science fiction. In America City, it is the mind of a US president wanting to build walls. Beckett looks from the inside. He goes into the mindset of the “others”.

Top of today’s literature, if you ask me.

After reading America City, it was somewhat of a shock to discover this record – Ainais Mitchell: Hadestown – Why we build the wall. I had not known this before.

I read, it is now a Broadway musical – I would love to see it.

To soothe my mind, I play a record dedicated to another vision of America – one of openness and acceptance:

How come boys and young men wanted to grow their hair long, going against the dominant social norms in the 1960s and 70s?

They were seen as girls, devalued and unmanly. Yet long hair became a way to demonstrate a youth revolt and a counter culture.

I am reading a lot of books, including music histories, for a book project on men and masculinities, in order to understand this change.

“All you need is ears”, Beatles producer George Martin argues, regarding the success of the Beatles – the leading long-haired band.

This is a good book regarding sound – a focused yet limited regarding the artistic contribution of the Beatles (and their sound as part of their artistic intention). Martin writes a lot about the technical issues and troubles with analog recording, with too few tracks and too much noise, and the text (written in the late 1970s) is more technical than emotional.

Yet this is the text of a record producer, not an artist, and should be judged on its own merits.

Much of what he says about analog recording, written before the advent of digital recording, which emerged some years later than this text (in the early 1980ies, with CDs supposed to represent “perfect sound forever”) is still relevant and interesting today. His book gives valuable knowledge, for example, on how to set up microphones, how to adjust for different instruments, and how to get the full sound of a band.

George Martin the producer and sometime-co-musician with the Beatles was never fully credited for his work. This is made very evident in the last part of the book. His complaints are reasonable, but his nagging tone, bringing up the theme, also reminds me of other recent music books I have read, in the direction, “I should have been paid x times more”. Artists and contributors often start out from artistic and idealistic reasons, but often end up – even if they sell well (or, especially in that case) – in conflicts regarding revenues, profits and egos. With maybe the ego part the hardest territory to negotiate. Alltogether, the in-depth books I read, including biographies of rock bands, artists and producers, describe a complaint against music capitalism. You can make a hit, but from then on, you are on the run.