Each year, since 2012, the Schengen Peace Foundation and the World Peace Forum award the Luxembourg Peace Prize, an award that “honors the outstanding in the field of peace”. The categories of the Luxembourg Peace Prize and their celebration “amplify the aims and goals of the World Peace Forum”. This year, the award for “outstanding peace organization” was given to Promundo.

The prize for “outstanding peace activist” was given to Masami Saionji and Hiroo Saionji of the Goi Peace Foundation and May Peace Prevail On Earth International, based in Japan. Thich Nhat Hanh received the award for “outstanding inner peace”.

Since its founding in Brazil in 1997, Promundo has worked in collaboration with partners to advance gender equality and prevent violence in over 40 countries around the world through research and evaluation, targeted advocacy efforts, and evidence-based educational and community-wide program implementation.

The research model and its links to implementation and innovation are a main part of the reason why Promundo received the prize. The prize statement specifically mentions “high-impact research”. Cf https://luxembourgpeaceprize.org/laureates/outstanding-peace-organization/2019-promundo/

The new research is also used in the recent State of the world’s fathers report (cf https://genderjustice.org.za/publication/state-of-the-worlds-fathers-2019-executive-summary/), which has drawn attention from media including The New York Times (https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/07/us/parents-fathers-role.html )

An important part of this research model was developed in Norway. Here is the background. And some ideas, how to follow up. 7 points, in all.

(detail of cover of Brandth and Kvande, editors: Fedrekvoten [The father quota], 2013)

(detail of cover of Brandth and Kvande, editors: Fedrekvoten [The father quota], 2013)

1

A main part of the Promundo research effort started from a new type of gender equality survey made in Norway in 2007 in a project and survey called “Gender equality and quality of life”. The survey included much more detail on gender equality than previous studies, including more perspective on men as well as women, more focus on gender equality not just in opinions but also practices, household care and work divisions, and well-being, health, conflict and violence.

2

The Promundo team developed the Norway survey framework into a more relevant and applied version applicable in the global south, focusing on violence and health issues, and expanding the practical experience questions. In the first 6-country survey (2009-11), about 60 percent of the questions were taken from the Norwegian survey. The Promundo survey was called IMAGES – International Men and Gender Equality Survey. Later, as Promundo and local partners have adapted the survey in new contexts, now more than 40 countries, many of those core questions have continued to be used. And the logic of gender equality being related to quality of life continues to be a key conceptual framework for the studies.

3

The survey design was further developed by the Promundo team in a variety of contexts and collaborations, including cooperation with researchers at the Centre for gender research, University of Oslo. In some respects, it goes far beyond the original Norwegian project, although main questions and an important part of the framework remained the same.

4

The Promundo development mainly concerned actions – more than structures. The original Norwegian model had more emphasis on mapping structural factors hindering or helping gender equality. Later, an independent development of the structural part of the design was made in a Poland-Norway study (2015). Several books and papers have been published from this project (called GEQ – Gender equality and quality of life).

The Poland-Norway study includes a “European blueprint” for a wider European project, combining a developed survey questionnaire with interviews and other data. See http://www.geq.socjologia.uj.edu.pl/en_GB/start?p_p_id=56_INSTANCE_ZGJFS82ydNo6&p_p_lifecycle=0&p_p_state=normal&p_p_mode=view&p_p_col_id=column-2&p_p_col_count=3&groupId=32447484&articleId=136474060 – The Promundo survey developments gradually also included structural factors.

5

However, a comparison of these partly independent developments of the same research model remains to be made. The original gender equality model focused on a number of broad factors to be investigated regarding the “state of gender in/equality” – how to measure this as an independent dimension, in society. These included gender equality in childhood and youth, in working life, public sphere, family and household, etc. The presumed factors were designated mainly as “structural” but included cultural variables also. The design had a social-psychological dimension.

6

Why has the research model been a success? It goes into a not so well known area, men and gender equality, combining action questions with structure questions and cultural questions. It is focused on important issues like health, caring, conflict and violence. It s not a “cover all” but offers a more detailed map than other research designs. Weak spots can be reduced by combining surveys with other methods.

A main reason for the success, in my view, is the combination of action and structure aspects. This means that trends and actions among men (and women) can be analyzed with more nuance and precision, regarding structural factors. You get more information on specific themes like violence, especially in the IMAGES version, and also tools to adjust for different social and cultural context, including five main dimensions of gender equality and (in less detail) other discrimination experiences. This makes for a powerful tool. It is a bit like a “meme”. Once you have this new mapping, you don’t want to be without it. In principle, investigation can be focused and targeted, and remain balanced, un-prejudiced.

7

Analyzing the total evidence, both the new European studies and the new global studies, is a main issue now. It needs to be done. Through our center at the University of Oslo, I have cooperated with Promundo in order to get this issue into the prioritized European research agenda. So far, without funding. I hope this will change, now.

There is no doubt whatsoever that this research effort on gender, men, women, violence and conflict, health and well-being – is of great importance not just in itself, but also in relation to other top priority research areas. How to reduce social discrimination. How to resolve burning questions of climate change. How to engage men and boys as well as girls and women in positive gender equality change.

Now more than ever, with so much interest in the topic of engaging boys and men by donors, governments and academics, the IMAGES dataset, together with the European dataset, is an unprecedented resource for analyzing these issues, and considering how to bring other topics into new surveys, and begin to carry out the survey again in the same countries 10 or 15 years later to assess change. Furthermore, given that Gates Foundation supported Promundo to unify and clean up the global dataset, Promundo and the University of Oslo are well-placed to carry out this analysis – building theory, identifying gaps and opportunities, and making IMAGES and European tools, questionnaires and interview guides even more available to interested researchers.

I have been reading Chris Beckett’s science fiction novel America city – a direct extrapolation from today’s events in the US. A hundred years from now, the south of the US is no longer liveable. Immigrants flow to the north. But to win the election, presidential candidate Slaymaker has to relieve the burden on the northern US states. His outspoken female (and partly feminist) advisor comes up with an advice: what about Canada, they have room for our refugees. With scary but quite probable results.

This book, together with the great conclusion of the Dark Eden trilogy, Daughter of Eden, makes Beckett my favorite current sci-fi author. There, he goes into the mind of a “ghostspeaker”, the kind of woman prophet-sayer that is otherwise not much credited in science fiction. In America City, it is the mind of a US president wanting to build walls. Beckett looks from the inside. He goes into the mindset of the “others”.

Top of today’s literature, if you ask me.

After reading America City, it was somewhat of a shock to discover this record – Ainais Mitchell: Hadestown – Why we build the wall. I had not known this before.

I read, it is now a Broadway musical – I would love to see it.

To soothe my mind, I play a record dedicated to another vision of America – one of openness and acceptance:

How come boys and young men wanted to grow their hair long, going against the dominant social norms in the 1960s and 70s?

They were seen as girls, devalued and unmanly. Yet long hair became a way to demonstrate a youth revolt and a counter culture.

I am reading a lot of books, including music histories, for a book project on men and masculinities, in order to understand this change.

“All you need is ears”, Beatles producer George Martin argues, regarding the success of the Beatles – the leading long-haired band.

This is a good book regarding sound – a focused yet limited regarding the artistic contribution of the Beatles (and their sound as part of their artistic intention). Martin writes a lot about the technical issues and troubles with analog recording, with too few tracks and too much noise, and the text (written in the late 1970s) is more technical than emotional.

Yet this is the text of a record producer, not an artist, and should be judged on its own merits.

Much of what he says about analog recording, written before the advent of digital recording, which emerged some years later than this text (in the early 1980ies, with CDs supposed to represent “perfect sound forever”) is still relevant and interesting today. His book gives valuable knowledge, for example, on how to set up microphones, how to adjust for different instruments, and how to get the full sound of a band.

George Martin the producer and sometime-co-musician with the Beatles was never fully credited for his work. This is made very evident in the last part of the book. His complaints are reasonable, but his nagging tone, bringing up the theme, also reminds me of other recent music books I have read, in the direction, “I should have been paid x times more”. Artists and contributors often start out from artistic and idealistic reasons, but often end up – even if they sell well (or, especially in that case) – in conflicts regarding revenues, profits and egos. With maybe the ego part the hardest territory to negotiate. Alltogether, the in-depth books I read, including biographies of rock bands, artists and producers, describe a complaint against music capitalism. You can make a hit, but from then on, you are on the run.

I am writing a book on young men breaking the gender barrier, “looking like girls”, growing their hair long in the 60ies and 70ies. Since I have other tasks it moves ahead a bit slowly. However, I read source material, especially, music biographies and books.

Recently I’ve read Townshend, Pete 2012: Who I Am, and Cushman, Marc: Long distance voyagers – the history of the Moody Blues (vol 1 1965-1979). Both contain interesting glimpses of the aversion against young men with long hair, and the way the hair was – so to speak – entangled with the new youth culture and progressive music.

As a music sociologist, I think they err on each side of the road. The two books have two different kinds of limitations.

Townshend lays out claims that he was the first doing power chords, and came up with other inventions, but he tells surprisingly little of the musical development in the band and how this impacted on the band relationships. It is more like, this band mate was strong / not so strong.

Cushman’s first part – a massive volume on the Moody Blues, will there be a second? – on the other hand, goes all into the music. The social context is more sparse. And the text uses a lot of space for listings of the band’s record sales, rather than the music itself. Nevertheless, it is clearly the new standard of scholarship on this band. Yet even here, I would have liked better analyses of what exactly the Moody Blues did, that was musically new.

Plus points in Cushman’s book include glimpses of Ray Thomas as alto flute player (and other musicians in the band) combined with the production talents of “the sixth moody” Tony Clarke. The credit to Clarke is well deserved. Decca was quickly learning and developing production technique developed at EMI (Abbey Road), and had very high standards from earlier recording also, surpassing EMI in some respects.

Cusham is great on how the Moodies – this unlikely bunch of old-style-singing long-haired guys with somewhat uncertain instrumental prowess – were allowed into the Decca “holiest of holy”, with the new Deram sound system (DSS), using two four-track recorders for better stereo. The band was supposed to play classical easy listening music. They barricaded themselves in Decca’s best studio, and ended up inventing something new, in the typical spirit of the day. The result was Days of future passed, one of the larger-selling LPs of all time.

Townshend mainly tells his own story, and somehow, I find the connections to the music rather weak. Fans of The Who may love the band for “inventing” this or “doing” that, but what actually happened, musically? Maybe this critique is unfair. Townshend does tell about his attempts to go further, to develop music beyond what the band had done so far. Later in the book he says that the band had done a lot of jumping and showing off, this would not do anymore.

Inadvertently he also tells a story of how “youth” wasn’t a staying ground for the attempted change.

I would have hoped Townshend took some self-critique for lines like “Hope I die before I get old” – but it is only implied. Like, maybe we DID smash up a few guitars too many. This is the tone of the book, as I read it. Townshend’s book has elements of defense that I won’t go into here. Maybe it spilled over, also into his judgement regarding things back then. Maybe a revised version could work this out better.

Bands like The Who took the “soft” message of the youth revolt and the counterculture, and “hardened” it. What happened, in that transition?

Cushman is fine on the music, but the wider social context, culture etc is often largely absent. How come these nice Birmingham lads, singing in almost 1950s style, were tuned on to the new youth rebellion and counter culture? I wasn’t much wiser, even after 700 pages.

Was the Moody Blues, on the road, a much more orderly affair, than The Who? Less misogynism and use of groupies? It seems so. The books show that male bands could have quite different wishes and setups. Although the different filtering of the story telling applied by the two authors may play a role.

Was the creative process of both bands hindered, by the music industry, the emphasis on commercial hits and best-selling albums? Again, it seems so. Despite variation the basic story is remarkably similar. Did this, all in all, create a more “masculine” idea of music? Now we are into speculation territorry – but it may seem so, yes. In various ways. Ending with the synth-pop of the 80s. Long-haired bands becoming dinosaurs, one way or the other. In fact, you maybe don’t need Reagan or Thatcher or digital sound problems into the equation, to predict the generally agreed-upon “bad sound of the 80s”. Just add “band pressure” working over time.

For example, listen to Moody Blues: Octave album, Steppin in a slide zone (1978). This sounds so bad, it maybe sounds great. If you like the 1980s sound. The flat synthetic sound reminding me of shoulder pads for men. Short hair once again. A kind of prophesy of the 1980s music letdown. Was Clarke out to lunch? Anyway, almost everyone agrees – with Octave, we are no longer into the “classic” period of the group. Artistic quality is falling. Why? Constant pressure from a commercial machine is – broadly – the best answer.

Octave was made after the group was totally exhausted, having made seven albums, later called “the classic seven”, in a period of nine years. Likewise, the Who and other groups were pushed beyond their limits, by very high demands from the record companies – entangled with their own wishes to make money, while the attention was there. “Do it now”, like Paul McCartney advises on Egypt station. Everyone remotely musical and socially engaged, 1965-75, felt like a storm was coming on, a counter culture expressed especially in music, a new truth that could not be denied, or at least, a new level of public discourse, an extension of democracy, “love” as in empathy, etc. So – the behaviors and conflicts of the bands – can be read in this larger perspetive, they were a new type of organizations, that tried to spearhead the youth revolution and the counter culture, but encountered great costs along the way.

Both books are well worth reading, if you are interested in this period, and its wider repercussions. They both give some guide into what to listen for – albums, songs – and a musical follow-up is interesting.

Best place to start with the Moody Blues is maybe To our children’s children’s children (1969), perhaps the most successful of their classic seven albums. Then try Questions, on A question of balance (1970). If this doesn’t rock you, nothing will.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-3571823-1378397821-2878.jpeg.jpg)

Best place to start with The Who – I have not decided yet. Listening to Tommy and Quadrophenia, The Who sells out, A quick one. The early stuff is often the most interesting. Maybe all in all the best intro, to get the feeling of the band, is The Who sells out.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-2229657-1338708241-6734.jpeg.jpg)

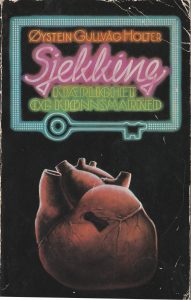

It feels strange, now, looking at a book I wrote many years ago.

The cover by Klaus Nordby is great – one of the best I have had, on the books I have published. You can see a key as well as a broken heart.

My own bookshelf copy is pictured here. It has been useful, opened many times.

What does the book say? Well – read it!

It is in Norwegian, and the title – translated – is “Dating, love and the gender market” (Sjekking, kjærlighet og kjønnsmarked). Pax, Oslo 1981.

The title starts with the Norwegian word “Sjekking” which is not so easy to translate (literal: checking, checking up). “Dating” is not quite precise, especially as it relates the practices in the US that were never common in Norway. Picking up a partner is maybe more realistic, on the whole, but the English words are not so clear.

There was a Swedish translation of the book (Hammarstrøm och Åberg, 1983) – using the word “Raggning” for the Norwegian “Sjekking”.

The cover (by Johan Petterson) shows another angle – a kiss above, a jungle below.

Note those eyes…

Sadly, the book was never published in English.

When discussing science fiction, and especially books like Heinlein’s Revolt in 2100, there is no way to get around Isaac Asimov’s Foundation trilogy. I remember, as a teenager, how it made a great impression on me. A way out, after having read Orwell’s 1984 and Huxley’s Brave new world.

(Picture: scan of the book covers, in my library)

Heinlein, like Asimov, gave a basically optimistic view of humankind – of the future – including men and masculinities. Was it naive? Is it any good, today? I remember the thrill of discovering the wide futuristic universe version of Asimov, and gradually, his greater narrative and plot. First, flight from increasing tyranny (Foundation). Second, confrontation (Foundation and empire). Third, an inner revolution (Second foundation). Rejecting empire from within. Does it still hold up? I will re-read and give a comment.

Starting here, with volume one, Foundation.

There is something utterly strange about reading these novels from 1951-52. I don’t mean all the external strangeness, carefully arranged in the books. I mean the inner strangeness, or alienation effect of reading this today, almost 70 years later.

It starts with cigars. Gentlemen, have a cigar. Preferably, a cigar “from Vega”. These gentlemen fill the scene, almost exclusively. Women are only present for illustration purposes, so to speak, in the first volume of the series. It is all about men – and a “hegemonic” competition of masculinity. There are two main types – the bully types, who use military force, and the smart types, who use religion, trade and other types of force.

There is no reflection on the absence of women. Even if the empire is said to consist of millions of worlds, with all kinds of variety of local star systems and societies, the rule seems the same everywhere – men are in, women are out. They don’t count in the big picture.

I find this amazing. It creates a kind of alienation effect (Brecht). It is unintended (not staged, like in Brecht’s plays), but that is the way it works for me, today.

Isaac Asimov creates a vast galactic empire, and a huge history, faced with breakdown, chaos and anarchy. The Foundation is created to reduce the coming age of darkness. Into this scenery, he paper-clips a report on American masculinity ca 1950.

Of course, decisions are made by men only, and of course, they smoke cigars.

These are the preconceptions that I find amazing, in an author otherwise so imaginative and coherent. Asimov is central in science fiction for good reasons.

The first volume of the series, Foundation, describes challenges met as the foundation is expelled from the central planet Trantor to the rim of the galaxy, and how it can defeat the powers surrounding it, in a period where central empire rule gradually dwindles. The heroes of the stories, placed 30 years apart, follow the “Seldon plan”, based on the science of “psychohistory”. This is not a paper clip, maybe, but a quite good approach to the optimal sociological functionalist analysis that dominated the agenda in 1950. If you can only count good enough, you will be able to predict how the future will unfold. Psychohistory is “mass” psychology, not individual psychology, Asimov underlined. He might have written “role system”. The idea was much the same. Like in Robert Heinlein’s work at the time (e g Revolt in 2100), there is a large belief in psychology and sociology.

The masculine hegemony issue is continuously referred to in the books, there is a lot of detail on how one man outperforms another, but is not reflected on “as such”, as matters between men, implying certain relationships to women and others, to “actors not present”. The silencing of this whole wider population – science fiction as masculine – was fairly typical of science fiction, one might say – at least until LeGuinn’s pathbreaking work Left hand of darkness, which put gender squarely on the agenda, and other seminal works of the 60s and 70s.

Foundation shows how men with “other” resources may win against men who use force and violence. They do this by mobilizing new resources (religion, trade) and outsmarting the bad guys. They adapt to a changing situation, the fall of the empire.

There are many positive aspects to the ethics, as I interpret it. Men of peace can win, over men of war. But there are also elements that can give me the shivers. How democratic is Asimov in this text?

The Foundation itself is described as partly democratic, although very influenced by a strong leader, who will reappear every generation in a video to give his message to his followers. The empire is ruled by an emperor, not an elected president, and does not seem very democratic, although there is a clear rule of law.

The alienation effect comes in, for example, when Asimov declares that the goal of the Foundation is to re-establish the empire. OK, this is 1950, he had not read more recent interpretations of a galactic federation or culture (LeGuinn, Banks, and many others). Is this really the goal? Should strong men, even in the “smart man” less violent version, dominate the world? Are his paper clips in fact portraits of Amerika – with a K, a binding to the Third Reich? At least, the idea of re-establishing a galactic empire with an emperor on top seems to stem more from Europe, than the US. Probably Asimov moderated and developed some of the themes I mention here,in later works, but what was actually written in 1950 is very interesting and important in its own right.

Foundation belongs to a period where gender was talked about and written about “innocently” – before the big gender challenge of the 1970s and later.

This change is easy to see in science fiction. Starting from the 1960s and attempts to renew and extend the field (e g the journal New worlds, and concepts like “inner space”), personal and gender issues became more reflected upon and problematized – especially by pioneer female authors, but also male authors.

The whole field has gradually been brought along, even though the feminist influence is sometimes superficial (women into masculine superhero types, etc.) The earlier, innocent writing on gender issues is what interests me, re-reading Asimov. It has a special charm – a way into conditions not formerly known, in 1950. Basically the empire is the idea on Asimov’s desk. The text describes how men work with such ideas.

Asimov’s men are very different from Philip K Dick’s men – for example. They represent power, not outcasts. Asimov is business-like, while Dick, writing a generation later, questions what happens, in those situations (cf The Martian Time-Slip). Dick has become a “survivor” – an author still selling to a young public – due to his problematization of power and consciousness. But it should be noted that these issues are very much on the mind of the young Asimov too, writing Foundation.

At first it may look naive, but then, the innocence gets interesting.

Robert Heinlein: Revolt in 2100 – a re-review

I have always liked science fiction. One of the first things I ever published, in a science fiction “fanzine” called Surg that I made as a youth in the 1960s, was a comparison of Huxley’s Brave new world, and Orwell’s 1984. I learned English by reading the new wave of science fiction novels that appeared in the late 1960s, and by the time I came to Le Guin’s Left hand of darkness, there was no going back. The paperbacks back then were fairly cheap even for a student, so over time I ended up with a large collection. Later, I have sifted through it, sorting out the least interesting stuff, but the collection remains ca 14 shelf meters. Sometimes, when I go back to novels I read back then, I think, well-well. Actually they still often have interesting ideas, but they don’t really work, today. These go to the “out” bin.

It is all the more a joy, therefore, to discover a novel that is still fresh and fine – or in a sense, even more so, in view of events today, including the threat of neo-authoritarian takeover of the western democracies.

Heinlein’s Revolt in 2100 pictures a future state of the USA taken over by right wing theocratic fundamentalists – working effectively through mass psychology and technology to control the population. It follows some of the same lines as The handmaid’s tale but was written twenty years before.

Heinlein does not have Atwood’s touch relating to gender, but what he does have, is interesting. It is a “young” Heinlein writing, not the “fatherly” pen of his later years. He is somewhat surprised that women can be team mates in the revolution against the tyranny – quite delightfully pictured, a true document of 1950s roles, brought a bit into the future.

There is less of the doomsday feeling than in some of Atwood’s novels. There is a real hope for democratic revolution, and the book plots this in detail. The discussion of psychological coercion and torture is impressive – and sadly, not dated at all. The masters have drones – Heinlein calls them eyes – spying on the population, and uses advanced strategies to squash all opposition.

The novel is often downright scary reading, compared to US developments today. It portrays mass indoctrination and fake news, and the emerging cult of the strong leader.

Like in Asimov’s famous Foundation trilogy, a special trick is needed to overthrow tyranny. There, it is the second foundation; here, it is the attack on the beliefs underpinning the dictatorship, before the coup is attempted.

Heinlein fans write that “he is the greatest” and I do understand what they mean. At his best – and this is frequent in this little gem of a novel – he reminds me of the great sociologist Talcott Parsons, who could be very progressive, although he was known as conservative. This is one of Heinlein’s most progressive books, and a forerunner of his most famous novel, Stranger in a strange land.

It is in parts very naive, 1950s, masculinist, and so on – but don’t let it bother you. If you have a hard day, and want to know how to overthrow tyranny – try this one.

I am re-reading Klaus Theweleit’s Male Fantasies (1977). I had it in book paper format, but someone ‘borrowed’ it, a long time ago, so my memory had grown hazy. Now it is available on the web. Re-reading is an interesting experience. Here is why this work is considered a classic in the (still small and new) field of masculinities studies.

«Male fantasies» revisited

Klaus Theweleit’s 1977 work Male fantasies is one of the classic texts of masculinity studies. This is because Theweleit focused on men and masculinities as a subject – beyond existing theories at his time, which mainly did not focus that way. Theweleit’s work was pioneering because it proposed a new research field through a dramatic example – the build-up of Nazism in Germany.

Theweleit used texts and images from the first part of the 20th century, mainly from the German soldiers and “Free corps” members after the first World War. His material documents an extreme fear of women as catalysts of change from the older patriarchal order. Reading this material, one wonders (in line with Theweleit), if the subordination of gender actually mainly went before the subordination of ‘race’, in the emerging totalitarian ideologies at the time (1920s, 30s). His material makes it likely that Nazism had large and still not fully analyzed masculine dominance underpinnings.

One main reason why this text is still often very relevant and eye-opening, is because it sticks to the phenomena, or tries to do so.

We will be examining a series of phenomena that move along the hazy border between “outright terror” and “mere convention.” Is there a true boundary separating “fascists” from “nonfascist” men?, he asks (p 27).

He finds that existing paradigms, even the critical ones, are not good enough. He discusses “latent homosexuality”, quoting Reich and Freud (p 54). Freud uses “mass commitments” (Massenbindungen) to the organizational dynamics that occur in hierarchical institutions. He notes Adorno: “Totalitarianism and homosexuality go together.” 55

Yet Theweleit critisised this type of use of Freudian concepts outside of therapy – it leads to arbitrary abstractions, he argued (p 56-57). An early perceptive argument, in hindsight. Instead he proposed a more empirical “masculinity in context” type of perspective (my term), focusing on the main phenomena in the material, regardless of existing theories.

So, as a kind of critique of simplistic theories of the authoritarian man, or even that Nazism can be reduced to latent homosexuality – here is his list of “observables”, focusing on the hazy border of what makes men fascists:

“The type of man we have before us “loves”:

—the German people, the fatherland

—the homeland soil, native village, native city

—the “greatcoat” (uniform)

—other men (comrades, superiors, subordinates)

—the troops, the parish, the community-of-blood among fellowcountrymen

—weapons, hunting, fighting

—animals (especially horses)

Aside from the animals, all of the love objects on the preceding list are ones we’ve encountered previously in connection with movements of resistance to women as potential love objects. In other words, these men claim to “love” the very things that protect them against real love-object relations!” p 61

Describing the wider mindset, especially the “Preussian” tradition among officers, he writes:

“Women have nothing to do with the “state.” A state employee is a slave, of course, but he is a slave of a man and himself a man. As such, he is closer to the state than even the wife of a general.” p 62.

Theweleit wrote before terms like “heteronormative” and “intersectional” were invented. Is he heteronormative? No. Instead he critisises heteronormative use of Freud (“latent homosexuals” as explain-away of Nazi appeal). Is his analysis intersectional? Yes clearly, if not very systematic. Postcolonial? Yes, in tendency. Imperialist ambition, social class, ethnicity, wounded pride – these are all into the picture.

His material shows that a main hate object of these men was the liberated (working class, and even communist) woman, often seen as a whore, a traitor. Democracy is whore-like. This is a main “threat factor”, engendering – so to speak – the racist and neo-imperialist ideology of Nazism.

Even if he stumbles sometimes, Theweleit does a marvelous job to exhibit the case. The return of neo-masculinism and authoritarian policies over the last decade makes his text on the masculine roots of these tendencies relevant today also. It is a pioneer work with continued importance.

I started my Christmas holiday with some new crime novels. This one, however, got the best of them. By accident I pulled it out from my book shelf, I had not read it since the early 1970s – and it got a hold on me. Much more exciting than the crime novels.

The excitement comes from the real-world historical drama, not a construed plot, from the detail, and from the way the author digests and analyses the detail. There is no doubt, this is a great mind at work. The world would have been a better place, if Trotsky instead of Stalin had followed Lenin, in the Soviet Union. I have critical points too, but for now, my message is just, read it.

How come capitalism does not work out, or only partially, according to the textbook rules of universalist free market competition and meritocracy? How come capitalism even in relatively gender-equal countries has stabilized at a two thirds income rule for women, compared to men? Why is inequality and discrimination still so common in global working life? Starting from practical, everyday experiences, my new book project will focus on the hows and whys of social inequality, especially, what can be known, using gender inequality as a “lens” or focus element. I want to go beyond broad exclamations that gender oppression is “closely linked to” or “intersectional” with other oppression forms like race and sexuality, or that different oppression forms tend to strengthen each other. Sometimes, they don’t. Instead, reduction of one form of oppression is bought at the cost of increase in another form. Current Western gender regimes that offer more gender equality to the upper middle class at the cost of harder ethnic oppression is a case in point. There is a substitute effect. In my book I will highlight the broader structural background of current gender issues, and how the struggle for gender equality becomes important, even if partly overlooked. My text will be critical. I think we have been seriously misguided.