Is gender a form of value, a form of capital? This paper, written in 1984, is not just a critique of superficial and essentialist ideas of gender, but also an attempt to understand gender from the specific viewpoint of value and commodity analysis. Instead of asking what follows from gender and how gender is performed, it asks what causes gender, what is the “stage script”, the way the performances are structured. Today, I might have written it differently, yet it has kept a critical edge that makes it interesting today also. The paper was published in Harriet Holter ed 1984: Patriarchy in a Welfare Society, University Press, Oslo 1984.

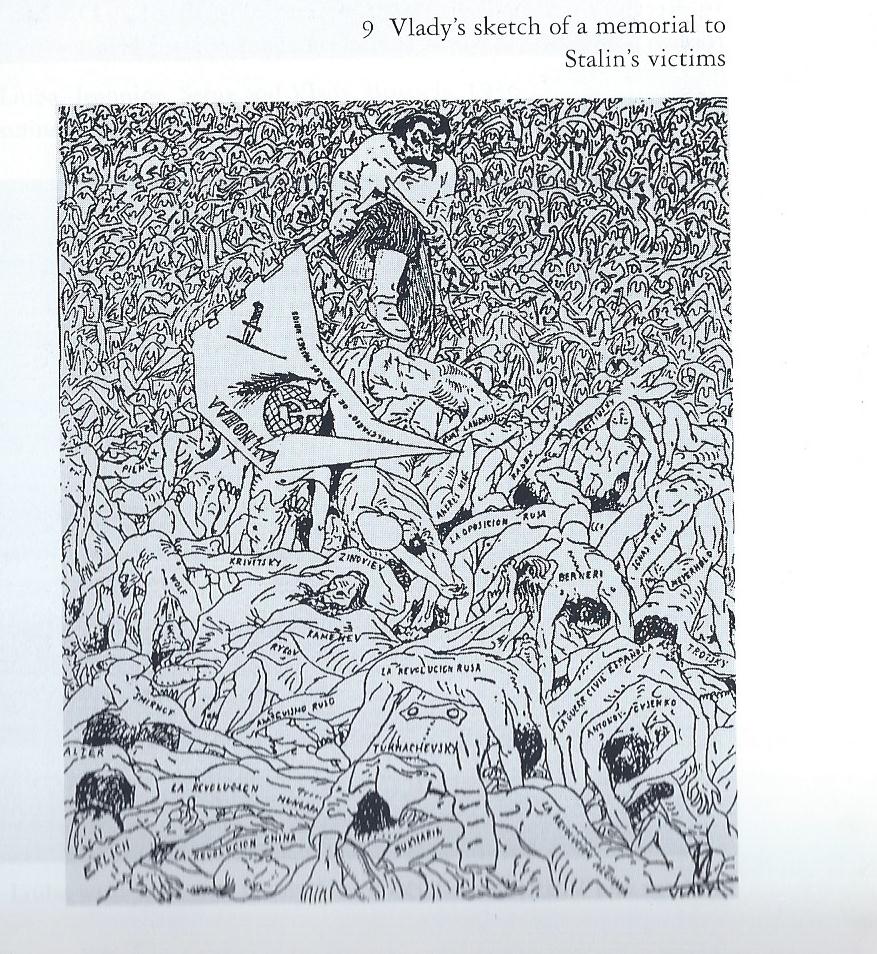

Stalin’s killings created the first holocaust, destroying a whole generation of revolutionaries, the bloodiest counter-revolution so far in history.

Stalin’s killings created the first holocaust, destroying a whole generation of revolutionaries, the bloodiest counter-revolution so far in history.

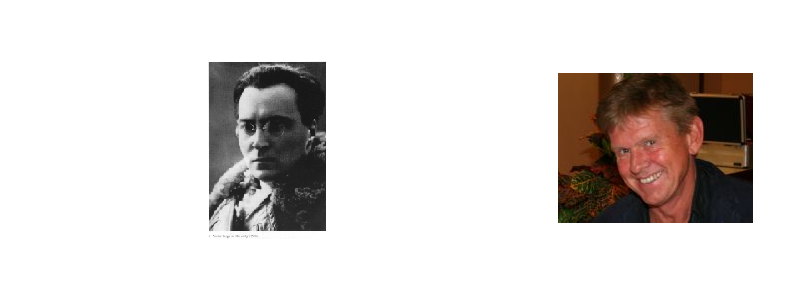

Victor Serge (summary), in Susan Weissman: The Course is Set on Hope,Verso, London, 2001.

Victor Serge (1890-1947) was a democratically oriented French-Russian left-wing intellectual, who was persecuted first in France, and later in the Soviet Union. He criticised power misuses by the Bolsheviks and joined the left opposition trying to stop Stalin from taking over, serving several prison sentences and barely escaping from the Soviet Union.

Serge wrote about Stalin’s repression:

“The average man, who cannot conceive that lying on this scale is possible, is taken unawares (..) Outrageous language intimidates him and goes some way to excuse his deception: reeling under the shock [of the Moscow trials] he is tempted to tell himself that there must, after all, be some justification of a higher order passing his own understanding. (..) In any case, it was not a matter of persuasion: it was, fundamentally, a matter of murder. One of the intentions behind the campaign of drivel initiated in the Moscow Trials was to make any discussion between official and oppositional communists impossible. Totalitarianism has no more dangerous enemy than the spirit of criticism, which it bends every effort to exterminate.” (Quoted by Weissman, p. 209).

Weissman’s book is very highly recommended.

As regards “lying on this scale” it is useful to consult Nazi propaganda minister Goebbels, who had the same conviction that if your lie is great enough, you will succeed.

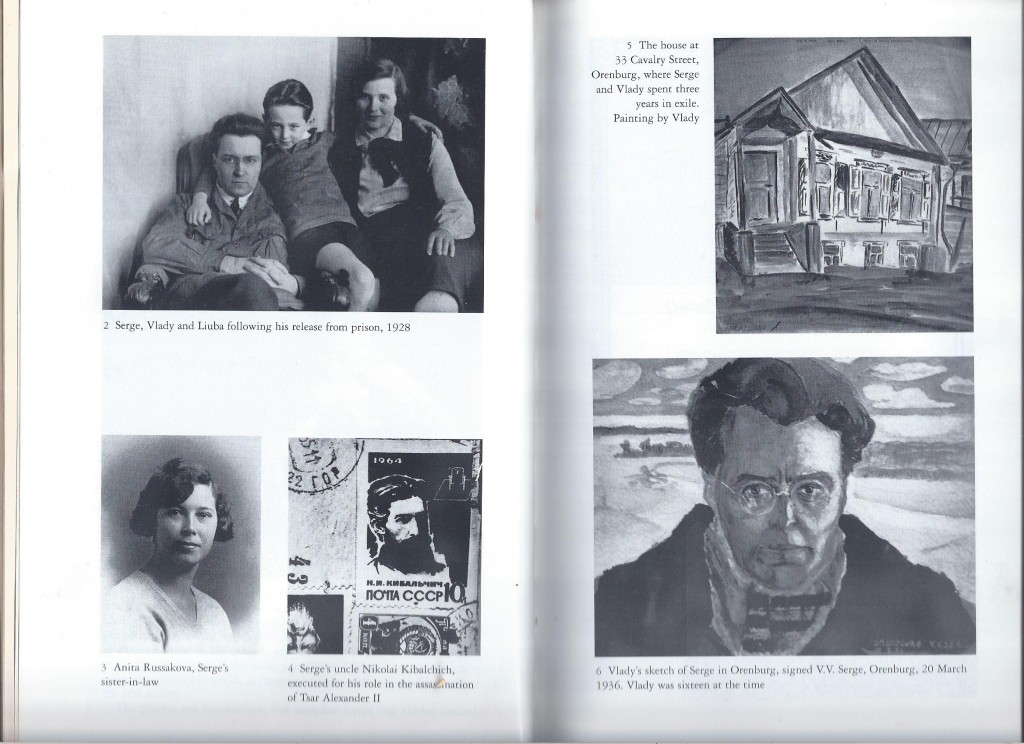

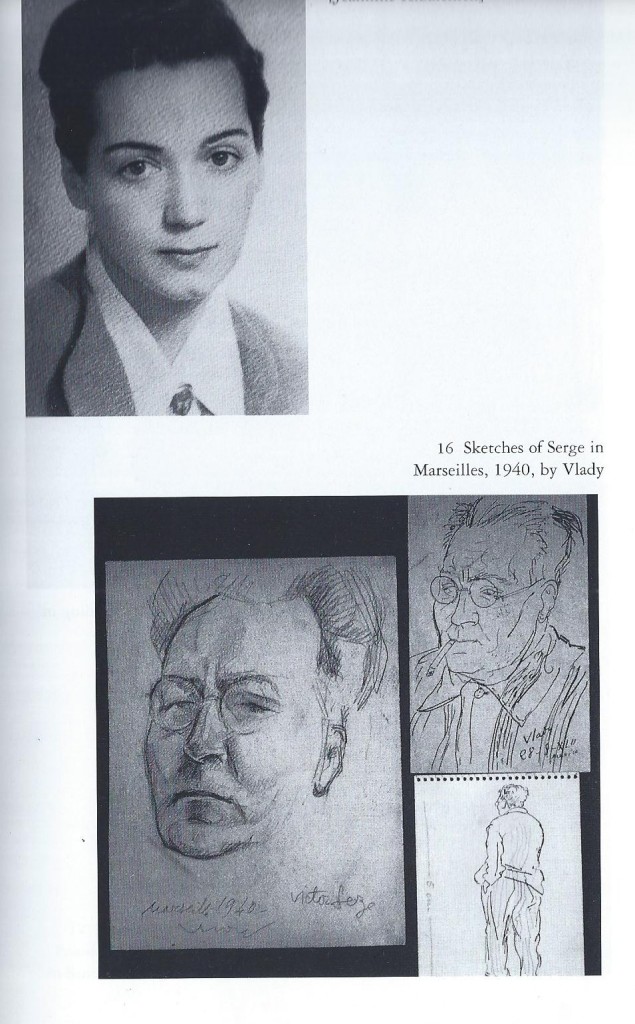

Weissman’s book includes photos and affectionate drawings by Victor Serge’s son, Vlady. A few are reproduced here, in the interest of further research.

Below, at left, Victor is pictured with his family, and at right, painted by his son, in exile, in the early 1930s, He does not look famished or depressed. This may have been made when the democratic alternatives still seemed to have a chance in the new Soviet Union.

However the Serge family were shocked by the news of increasing persecution. Here is Vlady’s impression of Stalin’s killings:

This is an utterly amazing and horrendous portrait, made by a young artist. Later research has shown that Vlady Serge’s “premonitions” were true. Millions of people lost their lives in Stalin’s death camps.

In the photos below, shown in Weissman’s book, the young artist is shown at top; next are his sketches of Victor having escaped Soviet persecution:

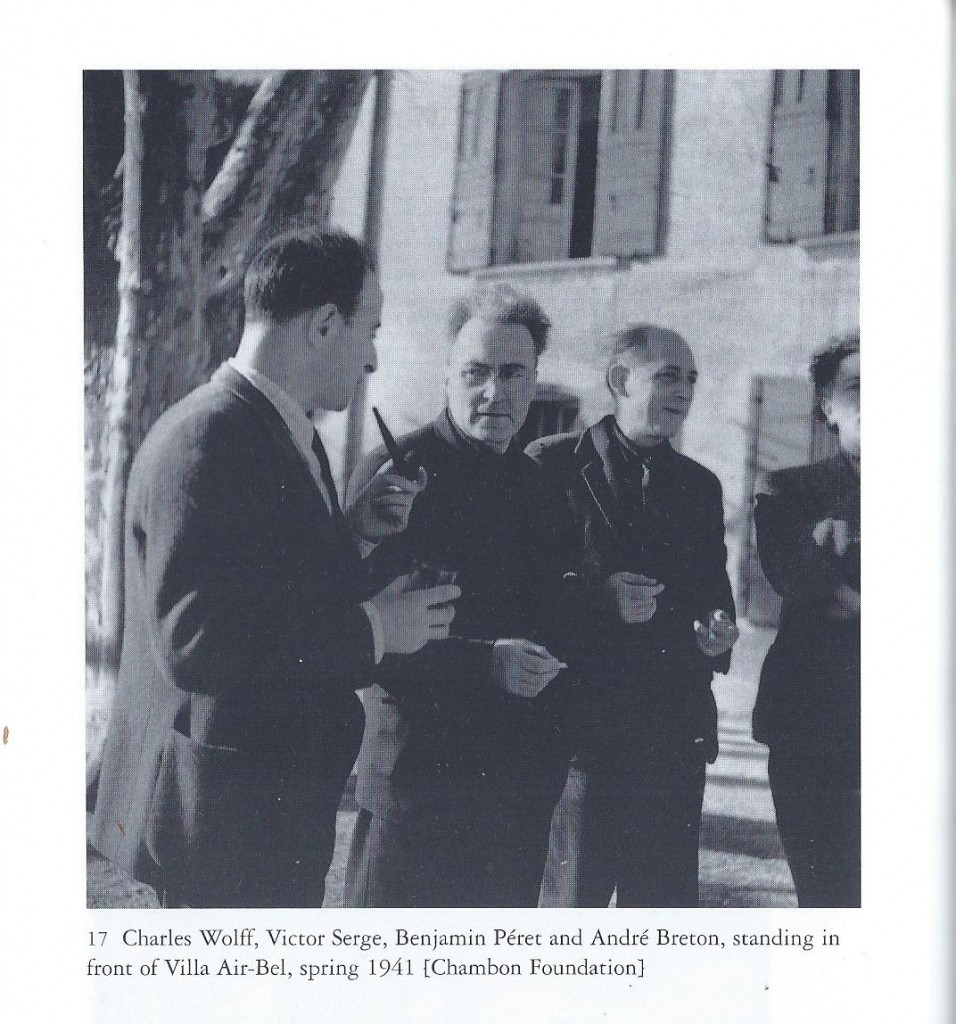

Vlady pictures his father troubled, and somewhat impatient, bottom right, hand in pocket. This is much like Victor emerges, in the photo below, in France. The men are perhaps discussing potentials for anti-nazi resistance. They seem to be filled with action, quite optimistic. Despite much persecution, Victor Serge did not hang his head.

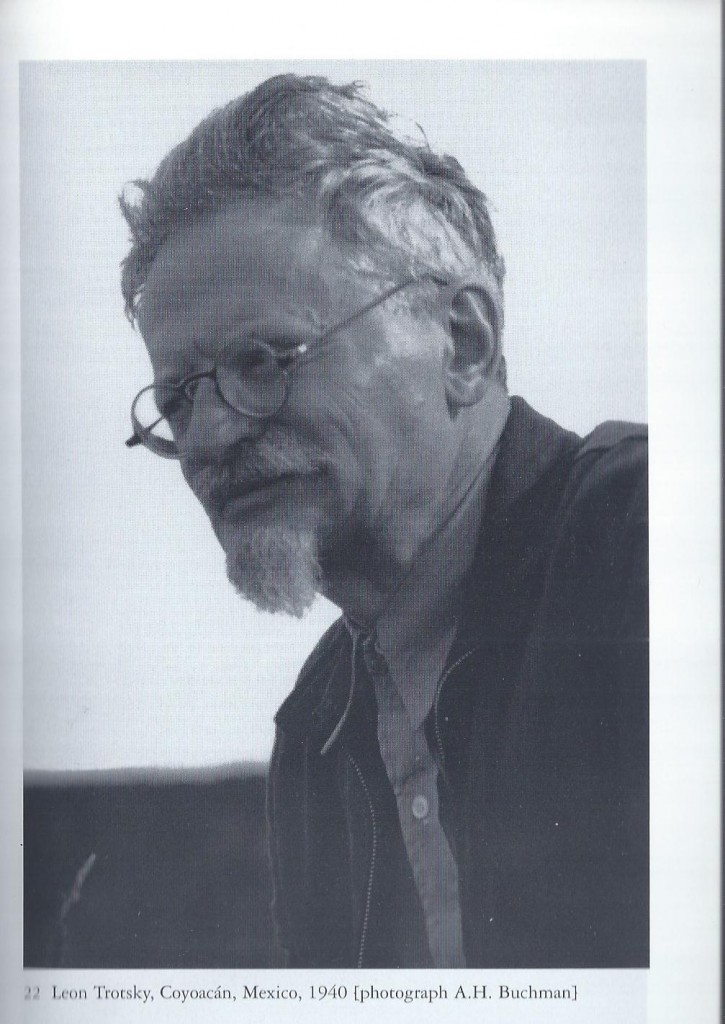

As the Stalinist repercussion hardened, all opponents were lumped into one case – enemies of the Soviet Union. Leon Trotsky, below, in a sense “profited” on this treatment, becoming “enemy number one”. Here is a picture of Trotsky, close to Serge’s visit.

This position of Trotsky and Trotskyism as the number one alternate to Stalinism was effectuated not least by Stalin himself – after one of his many hit-man gangs managed to kill the arch-enemy in August 1940.

Serge was symphathetic to many points made by Trotsky but he was not a Troskyite, as Weissman’s book documents. Serge did not live to write down a history or greater theory of what happened. Yet his independent viewpoints are very valuable and important.

See further

Holter, Ø. G. 2004e: “A theory of gendericide”, In Jones, Adam, ed.: Gendercide and genocide. Vanderbilt University Press, Norman

Holter, Ø. G 1984d: ”Sosialismens herredømme: kvinner og menn i Sovjetøkonomien” (Socialist Patriarchy: Women and Men in the Soviet Economy”), Materialisten 4, 1984, 41-62. See text.

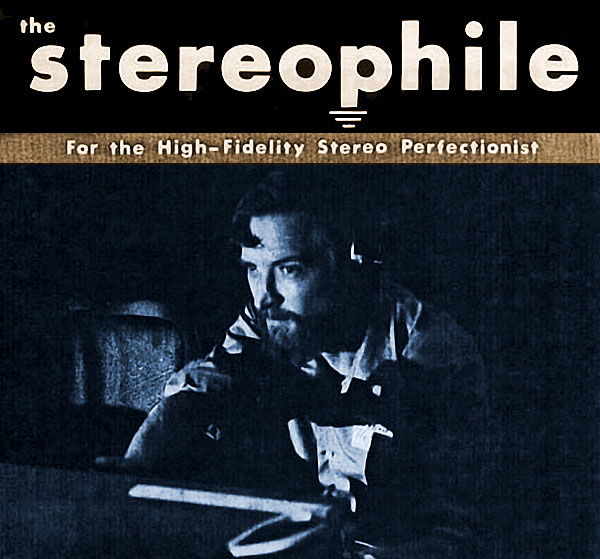

Are stereo and sound equipment companies, and magazines that review their equipment, out to maximize music – or money?

What is their primary interest, the product or the profit?

This debate has flared up again, related to Stereophile‘s 50 years anniversary, cf

http://www.stereophile.com/content/50-years-stereophile

The accusation from the critics is that Stereophile has turned out to become exactly what its founder J. Gordon Holt did not want – a commercially driven magazine.

“Fifty years ago this month, Vol.1 No.1, Issue No.1 of The Stereophile, published, edited, and mostly written by J. Gordon Holt out of Wallingford, Pennsylvania, hit the newsstands. Gordon had worked for two major audio magazines, High Fidelity and HiFi/Stereo Review (later renamed Stereo Review), and had been disgusted by those magazines’ pandering to advertisers. Not only was The Stereophile going to tell it like it was, it was going to judge audio components by listening to them—a heretical idea in those days of meters and measurements. “Dammit,” said Gordon, who died in 2009, “if nobody else will report what an audio component sounds like, I’ll do it myself!“, writes editor John Atkinson who took over from Holt in 1986.

In my view, the critique has some truth, the magazine is some of both. Readers have to learn to notice cue phrases like “in its price class” and read between the lines. Yet in my own experience, the advice has mainly been good: the product has had the main say, not the profit. Sometimes there is “snake oil” (profit-making, empty claims) involved, but then again, learning to use the magazine goes together with using other sources also, like Audiogon (and in Norway, hifisentralen).

In my case, I have followed advice from others, including Stereophile, whenever I could not listen myself. I have made some buying decisions mainly relying on the magazine reviews, and although I have found better alternatives later, in some cases, I do not regret making those decisions.

I would like the magazine to sharpen its critical edge, to be more clearly “with” the listener with limited means – not just those with big wallets. Besides keeping a sharp critical eye, there are some areas where Stereophile needs improvement. One is mid-level equipment (in terms of price), not just top level plus a bit entry level. Lower mid-level is probably the level of most readers. Secondly, top level equipment gradually drifts down to mid-level as time goes by, and the magazine should give more space to second hand options. Thirdly, it should give more space to how systems sound as a whole, not just this or that component, but its synergy with the rest.

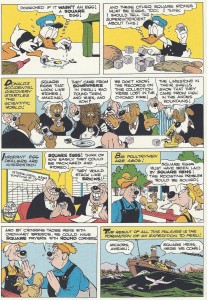

According to the foreword by Donald Ault in the new Fantagraphics Books series “Donald Duck – Lost in the Andes – by Carl Barks” (2011) , Barks – not Disney – was the one who invented most of the Donald Duck scenery and characters, including Uncle Scrooge. “Barks was perhaps the most widely read but least-known author in the world”.

I was six or seven years old when I started to recognize Barks’ stories, in the late 1950s. I would make a corn-flake bowl when I got home from school, reading Donald Duck when it arrived each week. A new Barks series was a special treat. I knew it only through a sense of the best drawings. Here we are again – top quality.

This is still my impression when, sixty years old, I reread his “Lost in the Andes” story. This layman story (Barks was an autodidact) is just great, regarding adventure, capitalism, US fingers on south America, and general attitude – a true artistic wonder. The foreword helped me me put words to several things I felt as a boy also, not least, the film-like technique, the great attention to timing, in his drawings.

Here is an example of Barks making fun of power in modern society (click on image to get a full version).

“Important egg dealers are interested”…indeed.

Although the foreword describes how Barks died without much recognition, is is a bit curious, by 2012, that it does not more clearly mention his critical view of capitalism, which was a red thread in his best work.

The book as a whole is not up to the standard of “Lost in the Andes”, the long adventure story where Barks had free hands, it also contains shorter and less interesting stories – illustrating the editorial constraints laid on this remarkable artist.

A kind of thought ray has a world locked up in deadly battle with the human colonizers.

The basic theme of Harry Harrison’s Deathworld (1960) has not lost its relevance, and the novel makes for a good reread, and although not great literature, it is up from e g his Stainless steel character. The man gambles but he also thinks and feels. Very interesting concerning the period development in science fiction. Camouflaged as science fiction, we get a critique of military logic, and a sketch of another form of society. Not bad, even if some of the writing is poor. I found Deathworld while going through my SF library, to rediscover, and enjoy.

Erving Goffman (1922-82) var en av de store sosiologene i det tyvende århundret, ved siden av Robert Merton, og noen få andre, slik jeg ser det. Derfor siterer jeg ham, om maskulinitet og skam, på toppen av hjemmesiden.

Noen mener at Goffman var evig mistroisk, og dessuten nokså markkrypersk og uteoretisk. Han prøvde seg som kjønnsteoretiker på 1970-tallet (bl.a. “The arrangement between the sexes”), men det ble ikke en fanesak, hverken for sosiologene eller for feministene, å lese ham. Han prøvde seg som samfunnsteoretiker (“Frame Analysis”) men fikk en god del kald skulder fra fagfellesskapet. Det var greit så lenge han holdt seg til “sitt” område, litt dramaturgisk sosialpsykologisk bidrag fra sosiologiens verden. Da han forsøkte seg på mer syntetiserende teori, fikk han mindre støtte.

Jeg kjøpte og leste flere av Goffmans bøker på 70-tallet, og kopierte en del av hans artikler, men dessverre har mye av dette blitt borte underveis, fordi det har blitt lånt ut, uten at jeg fikk det igjen. Jeg får bare håpe at andre ble tilsvarende interessert.

Goffman er fortsatt interessant og relevant bl.a. fordi han var en anti-strukturalist før sin tid. Hans tenkemåte er riktignok typologiserende, men den har sin styrke i “dramaturgien”, dette at han tolker roller i et dramatisk lys, en sans for plot, narrativ, “se hva som skjer”. Og skal man forstå Goffmans bidrag må man lese med, ikke mot, man må forstå at han også selv skriver innen denne litt mistroiske dramaturgien. Det å knipe ham på litt uryddige typologier eller manglende sans for mikro, meso og makro-nivåer og strukturenes betydning, slik han ofte ble kritisert på 70- og 80-tallet, blir for smålig og utvendig. Det er er mer å lære, men man må gå innvendig til verks.

Derfor holder det heller ikke å bruke uttrykket for det viktigste teoribidraget han skapte, “rammeanalyse”, som et alt-mulig-begrep som skal fange enhver prosess eller enhver diskurs. “Ramme”, hva er det? Det hjelper ikke å kalle det “kritisk” rammeanalyse,. Vi er alle innrammet. Vi er alle dømt til å bli tolket av den andre, som de Beauvoir, Sartre og mange andre skrev om. Det å vise ansikt er ikke bare en etisk handling (Levinas) men også noe som kan medføre ytterligere innramming. Sosiale kontekster skaper sine praktiske logikker (Bourdieu). Sosiale strukturer, klasser osv holder aktører i systemer som opprettholder makt og hierarki. Dette er kjernen i Goffmans analyse.

Goffman er ikke den beste guiden for å forstå hva slags samfunnsstrukturer som skaper slike negative rammer eller tolkninger, i denne brede betydningen – men han er meget skjerpet i forhold til å forstå hva som skjer innen slik samhandling. Ofte i samme retning som Torstein Veblen, som sent på 1800-tallet skrev om bruken av kvinner som “tegn” i borgerskapet i den avanserte kapitalismen i Amerika.

Goffman beskrev begivenhetene innen feltet moderne sosial ulikhet mer overbevisende, enn strukturene som skapte ulikhetene. Han blir vanligvis ansett som psykologisk orientert sosiolog (sosialpsykologi) men kan også tolkes som en småskala-økonomi, orientert ut fra bredere sosial resiprositetsøkonomi (Gouldner). Hans analyser har viktige likheter med senere poststrukturalistisk teori. Han hevder ofte, i tendens, at aktørsystemet virker godt nok som det er. Det er ikke nødvendig å teoretisere bakenforliggende “strukturelle” forhold. Noen kan hevde at, med Goffmans porsjon av mistro, og vekt på en markedaktør-aktig sosial figur som handler på grunnlag av nytte eller gevinst, i et spill om status – så trenger man ikke “bakenforliggende strukturer” for å holde etablissemanget på plass. Det forklarer seg selv, gjennom aktørsystemet. Et interessant eksempel på hvordan Goffman etterhvert knyttet mer an til institusjoner og strukturer, er nettopp hans kjønnsanalyse, også som eksempel på hans arbeidsmetode, etterhvert som hans dagligdagse skam- og pinlighets-orienterte første runde av empirisk sosiologi (Stigma, osv) møtte motstand.

“Alle menn rødmer”? Hvordan ble det mottatt? – Det vakte motstand, reaksjon, og eneste grunn til at Goffman vant gjennom, så og si, var at han ble “reddet” av praktikerne, inkludert psykologer som så at begrepsdannelsen var nyttig, i tillegg til liberale fagfeller i sosiologi. Uten dem hadde han neppe blitt publisert.

I den relativt lite faglig påaktete boken Gender Advertisments (1976), tolker Goffman reklamebilder i lys av teori om kjønnslikestilling. Teorien er enkelt utformet – menn dominerer. Det er mest bilder, mindre tekst, og boken ble utgitt i A4-format. Goffman beskriver hvordan reklamen, ved å vise folk med bestemte utseender og kroppsposisjoner, relativ høyde, positurer, gester, og andre virkemidler, gjenskapte en underordningsposisjon for kvinner og en overordningsposisjon for menn. Han bruker innrammingsanalysen metodisk videreutviklende, ut fra en bestemt begrenset kilde, fotografiske reklamebilder, til å si noe om en bestemt strukturell kontekst, reklameindustri, og dens innvirkning på samfunn og kultur. Innramming ble beskrevet mest i termer av substantiver og type ramme-virkemiddel, men teksten er skrevet først og fremst ut fra en underliggende tanke, slik jeg tolker den, dette var hans underliggende teoretiske ambisjon – med trykk på verbet, plasseringen, det å bli (inn)rammet.

Når mannen står over henne, i bildet, eller opptrer beskyttende, i forhold til det ytre rom, og fremheves som person med kvinnen som bakgrunnen, (osv.) i bildene fra amerikanske reklamer på 70-tallet – så er det fordi han har blitt plassert der, det er (i poststrukturalistiske termer) en narrativ, og det er denne sekvensen av plassering som særlig interesserte den “senere” Goffman som forsker, etter at han hadde mottatt og fordøyd kritikk for sine tidlige bidrag. Han har blitt interessert i strukturen og prosessen, samtidig som han holder seg til selve resultatet, bildet av aktørene.

Goffman’s tolkning kan på overflaten virke stillestående, noe som delvis skyldes typen materiale og kontekst han beskriver. Han er ikke verdens beste historiske sosiolog eller prosessanalytiker, men jeg regner ham likevel som en “verb-orientert” forsker, snarere enn en typologisk eller “substantiv-orientert” forsker. Mer “mummitroll” enn “hemul”, ut fra en nordisk skildring, nord for det Connell kritiserer som nordlig teori (Southern Theory, 2007) . Skillelinjene i teoriutvikling beskrives i min avhandling om sosial formanalyse (1997), der jeg kritiserer “abstraktisme” og overdreven tro på substantiver, kategorier eller typer, utviklet ut fra vår tids samfunnsform.

Selv om Goffmans forståelse av prosesser på samfunnsnivå og hans analyse av bredere historisk endring var begrensete, var han på sitt beste nettopp når han opererte i landskapet mellom historie og sosiologi, i framhevingen av aktørsystemets egenvekt, innen en vitenskapelig horisont som dengang var dominert av typologer og strukturalister. Han var empirisk orientert, og observerte hva folk sa og gjorde, særlig for å oppnå sosial status. Han vektet sin analyse ut fra det pinlige og skamfulle i moderne sosialt liv, og gikk videre, derfra. Hans tenkning var en utfordring for det middel-konservative maktens sentrum i datidens Amerika. Det at han kanskje mistroisk rygget litt tilbake idet han italesatte og begrepsfestet dramaturgien, kan ikke brukes mot ham – han var en innsiktsfull og modig teoretiker.

Goffman ble delvis lest mot sin hensikt, som om han mente at alt sosialt liv handler om makt, stigmatisering og innramming. Foucault, som levde noe lengre enn Goffman, ble tolket på samme måte. Disiplineringen gjalt alltid og overalt. Foucault fikk anledning til å imøtegå denne tilsvarende forflatende tolkning av hans teori – Goffmans rammeanayse og Foucalts disiplineringssystem handler mye om det samme.

Det stemmer ikke, sa Foucault i et sent intervju (gjengitt i boken Remarks on Marx, 1991) at makten bare er allestedsnærværende eller overalt. Den utøves på noen måter av alle, men særlig av visse grupper og klasser. Foucault ble her tydelig på at bl.a klasseanalyse er viktig for disiplineringsanalyse og diskursanalyse, og kritisererer forflatende tolkning av hans teori. Goffman ville vært enig.

Under the heading, Does feminism have a bad reputation?, almost 50 participants attended the start conference of the new Feminist Forum at the University of Oslo, at Chateau Neuf Nov 26, with presentations by Charlotte Myrbråten, former editor of the feminist journal Fett, and myself. Mostly students, about a quarter men.

The debate concerned whether feminism today has become a mark of disrespute or negative reactions. In some student circles, saying “I am a feminist” is a risky proposition.

Yet the reaction against what is perceived as “feminism” also has some understandable reasons. For example, when feminism becomes the word for women-only-interests, or upper-middle-class-career-interests. Main reasons why feminism gets into disrespute were discussed, including a belief that feminism only favors women (and is against men), only the middle class, or that it is no longer needed (the goals have been achieved, gender equality is here already).

The debate did not provide “answers”, but it was interesting, fun, open and smart – a good start for the new forum. A debate like this would scarcely have been possible twenty years ago. At that time, the “hard” front lines between the genders would have been much more marked. Today, Myrbråten argued that masculinits, also, could be feminists. This idea would hardly even have been understood twenty years ago. There has been a major change of climate, and it is most noticeable among young participants in the discussion.

The debate underlined the need to know, to create better analyses and theories, and for better research.

Ever since the “Gender equality and quality of life” survey results came in, in 2007, I have worked with improvements of the data base.

Version 5 of the data base has now been constructed and internally tested, eliminating errors. The data base versions 1-4 constructed the main gender equality indexes, as well as easier access to important variables. Version 5 follows this, with new useful variables e g regarding sickness leave, parenting, violence experience, and many other topics.

The data base has 2805 respondents. The variable set is now larger, total 820 variables. Some of these are temporary variables only, but at least 500 variables is realistic.

This is quite a bit above the global gender equality “index approach” with – at best – thirty or fifty variables.

In many ways, the data set is unique. It was constructed in terms of gender equality, and has helped create a new map of gender equality developments.

Why use time and resources for a phd course on “archaic” gift exchange theory, outlined by nowadays somewhat “obscure” theorists like French structuralist Claude Levi-Strauss?

Because, perhaps, there was “something in it”? Something true, across sciences? Something with women “between” men, not just “opposed to” men?

This course enlists main University of Oslo professors as well as independent researchers, as speakers (including Thomas Hylland Eriksen, Elisabeth L’orange Furst, Jorun Solheim) – the researcher interest is collective. Starting from a measurable affair, “who moves in marriage”, we will highlight and develop improved gender equality research.

Although I listened a lot to Talking heads when their music appeared in the late 1970s, I was already in my late twenties, and my main or “formative” experience was from the late 1960s, so this was a kind of repeat of what I had heard before. It was only gradually that I came to realize, a better kind of repeat.

At the time, I had my musical radar open, and got their debut album “77” quite soon, but it was their follow-up “More songs about buildings and food” that really gripped me, beyond my first-round music socialization. I was amazed by the combination of “strange” and “melody”, even pop-hooked melody. Along with quirky but understandable lyrics – “I just want to be with the girls”.

For some reason, I lost interest in Talking heads in the early 1980s, and never listened so much to their other albums.

Time for a change.

I’ve bought “Remain in light” in the 2006 remastered edition (Rhino), and am sorry I missed it in the first place.

Like “More songs”, “Remain in light” is fresh and interesting, today. The first is still in a kind of “Americana”, it is within the bubble or gum wrap of commercial ‘pop’, the second more into ‘world music’. Together they make a shining path in the development of popular music.

Why do I like this music? My premier honor does not go to Byrne’s vocals or Harrison’s keyboards, or to others, although they are all very good. It goes to the bass playing of Tina Weymouth. She deserves a position in the hall of fame of rock music. This “verve” lady plays a great and deep bass, better than almost all I know of, when it comes to making the bass integrate with the ensemble effort, slowing it down, moving it up, based on melody, a greater sense of the whole, not just rhythm. Yes, her bass and the band playing can sound repetetive and tiring at times, but I think this is much due to the role she was given. When she is offered the chance to break loose, she is great. Her bass is the overlooked structure of the Talking heads’ success.

I was not aware of her later career with the Tom Tom Club. A new live CD sounds very good – to be checked out.