Each year, since 2012, the Schengen Peace Foundation and the World Peace Forum award the Luxembourg Peace Prize, an award that “honors the outstanding in the field of peace”. The categories of the Luxembourg Peace Prize and their celebration “amplify the aims and goals of the World Peace Forum”. This year, the award for “outstanding peace organization” was given to Promundo.

The prize for “outstanding peace activist” was given to Masami Saionji and Hiroo Saionji of the Goi Peace Foundation and May Peace Prevail On Earth International, based in Japan. Thich Nhat Hanh received the award for “outstanding inner peace”.

Since its founding in Brazil in 1997, Promundo has worked in collaboration with partners to advance gender equality and prevent violence in over 40 countries around the world through research and evaluation, targeted advocacy efforts, and evidence-based educational and community-wide program implementation.

The research model and its links to implementation and innovation are a main part of the reason why Promundo received the prize. The prize statement specifically mentions “high-impact research”. Cf https://luxembourgpeaceprize.org/laureates/outstanding-peace-organization/2019-promundo/

The new research is also used in the recent State of the world’s fathers report (cf https://genderjustice.org.za/publication/state-of-the-worlds-fathers-2019-executive-summary/), which has drawn attention from media including The New York Times (https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/07/us/parents-fathers-role.html )

An important part of this research model was developed in Norway. Here is the background. And some ideas, how to follow up. 7 points, in all.

(detail of cover of Brandth and Kvande, editors: Fedrekvoten [The father quota], 2013)

(detail of cover of Brandth and Kvande, editors: Fedrekvoten [The father quota], 2013)

1

A main part of the Promundo research effort started from a new type of gender equality survey made in Norway in 2007 in a project and survey called “Gender equality and quality of life”. The survey included much more detail on gender equality than previous studies, including more perspective on men as well as women, more focus on gender equality not just in opinions but also practices, household care and work divisions, and well-being, health, conflict and violence.

2

The Promundo team developed the Norway survey framework into a more relevant and applied version applicable in the global south, focusing on violence and health issues, and expanding the practical experience questions. In the first 6-country survey (2009-11), about 60 percent of the questions were taken from the Norwegian survey. The Promundo survey was called IMAGES – International Men and Gender Equality Survey. Later, as Promundo and local partners have adapted the survey in new contexts, now more than 40 countries, many of those core questions have continued to be used. And the logic of gender equality being related to quality of life continues to be a key conceptual framework for the studies.

3

The survey design was further developed by the Promundo team in a variety of contexts and collaborations, including cooperation with researchers at the Centre for gender research, University of Oslo. In some respects, it goes far beyond the original Norwegian project, although main questions and an important part of the framework remained the same.

4

The Promundo development mainly concerned actions – more than structures. The original Norwegian model had more emphasis on mapping structural factors hindering or helping gender equality. Later, an independent development of the structural part of the design was made in a Poland-Norway study (2015). Several books and papers have been published from this project (called GEQ – Gender equality and quality of life).

The Poland-Norway study includes a “European blueprint” for a wider European project, combining a developed survey questionnaire with interviews and other data. See http://www.geq.socjologia.uj.edu.pl/en_GB/start?p_p_id=56_INSTANCE_ZGJFS82ydNo6&p_p_lifecycle=0&p_p_state=normal&p_p_mode=view&p_p_col_id=column-2&p_p_col_count=3&groupId=32447484&articleId=136474060 – The Promundo survey developments gradually also included structural factors.

5

However, a comparison of these partly independent developments of the same research model remains to be made. The original gender equality model focused on a number of broad factors to be investigated regarding the “state of gender in/equality” – how to measure this as an independent dimension, in society. These included gender equality in childhood and youth, in working life, public sphere, family and household, etc. The presumed factors were designated mainly as “structural” but included cultural variables also. The design had a social-psychological dimension.

6

Why has the research model been a success? It goes into a not so well known area, men and gender equality, combining action questions with structure questions and cultural questions. It is focused on important issues like health, caring, conflict and violence. It s not a “cover all” but offers a more detailed map than other research designs. Weak spots can be reduced by combining surveys with other methods.

A main reason for the success, in my view, is the combination of action and structure aspects. This means that trends and actions among men (and women) can be analyzed with more nuance and precision, regarding structural factors. You get more information on specific themes like violence, especially in the IMAGES version, and also tools to adjust for different social and cultural context, including five main dimensions of gender equality and (in less detail) other discrimination experiences. This makes for a powerful tool. It is a bit like a “meme”. Once you have this new mapping, you don’t want to be without it. In principle, investigation can be focused and targeted, and remain balanced, un-prejudiced.

7

Analyzing the total evidence, both the new European studies and the new global studies, is a main issue now. It needs to be done. Through our center at the University of Oslo, I have cooperated with Promundo in order to get this issue into the prioritized European research agenda. So far, without funding. I hope this will change, now.

There is no doubt whatsoever that this research effort on gender, men, women, violence and conflict, health and well-being – is of great importance not just in itself, but also in relation to other top priority research areas. How to reduce social discrimination. How to resolve burning questions of climate change. How to engage men and boys as well as girls and women in positive gender equality change.

Now more than ever, with so much interest in the topic of engaging boys and men by donors, governments and academics, the IMAGES dataset, together with the European dataset, is an unprecedented resource for analyzing these issues, and considering how to bring other topics into new surveys, and begin to carry out the survey again in the same countries 10 or 15 years later to assess change. Furthermore, given that Gates Foundation supported Promundo to unify and clean up the global dataset, Promundo and the University of Oslo are well-placed to carry out this analysis – building theory, identifying gaps and opportunities, and making IMAGES and European tools, questionnaires and interview guides even more available to interested researchers.

How come boys and young men wanted to grow their hair long, going against the dominant social norms in the 1960s and 70s?

They were seen as girls, devalued and unmanly. Yet long hair became a way to demonstrate a youth revolt and a counter culture.

I am reading a lot of books, including music histories, for a book project on men and masculinities, in order to understand this change.

“All you need is ears”, Beatles producer George Martin argues, regarding the success of the Beatles – the leading long-haired band.

This is a good book regarding sound – a focused yet limited regarding the artistic contribution of the Beatles (and their sound as part of their artistic intention). Martin writes a lot about the technical issues and troubles with analog recording, with too few tracks and too much noise, and the text (written in the late 1970s) is more technical than emotional.

Yet this is the text of a record producer, not an artist, and should be judged on its own merits.

Much of what he says about analog recording, written before the advent of digital recording, which emerged some years later than this text (in the early 1980ies, with CDs supposed to represent “perfect sound forever”) is still relevant and interesting today. His book gives valuable knowledge, for example, on how to set up microphones, how to adjust for different instruments, and how to get the full sound of a band.

George Martin the producer and sometime-co-musician with the Beatles was never fully credited for his work. This is made very evident in the last part of the book. His complaints are reasonable, but his nagging tone, bringing up the theme, also reminds me of other recent music books I have read, in the direction, “I should have been paid x times more”. Artists and contributors often start out from artistic and idealistic reasons, but often end up – even if they sell well (or, especially in that case) – in conflicts regarding revenues, profits and egos. With maybe the ego part the hardest territory to negotiate. Alltogether, the in-depth books I read, including biographies of rock bands, artists and producers, describe a complaint against music capitalism. You can make a hit, but from then on, you are on the run.

20 000 pupils – or more – have protested in Norway, against the lack of climate awareness on the behalf of the politicians. The protest is spreading all over the world.

Not strange – the youth are the ones who will face the costs of the actions – or inactions – we do now.

The movement, now, is much focused on the young against the old. A well known division, “age”, comes into sociological play. “Hope I die before I get old”, like the Who put it, back in the radical 1960ies. Even in gender-equal – supposedly – Norway – we get voices like way back then. “Why don’t these youths go back to school”. Demonstrating for the environment is not a legal ground for being absent, in most of the schools.

Norway seems to react like a dinosaur slightly before the catastrophy hits. It is sad to see.

Yet this is the very fare that provides the food for a new opposition, a new youth rebellion, going beyond the one in the 1960s. Now, like then, the adult world and the establishment create barriers, obstacles, and try to brush off the new insight. Later they will try to co-opt it, make it into the system in “harmless” ways – to judge from historical experience of the last youth revolt. Now it is maybe happening again. Yet these errors can be avoided. The situation is different, there is more focus, and the pupil revolt is supported by scientific evidence. The 68-ers said the whole system was bad. Now, the approach is more limited – the system is bad, if it does not correct the environment crisis.

There are plus and minuses to the “critical” approach back then – and the environmental approach now. The usual end of the story – youthful rebellions through the times – is that the youth revolt does not hold out. It has maybe some victories but mainly cultural, society is not much changed, and may even go back to worse practices due to the “humiliation” of the childish critique of the youth and its counter culture.

However, now the clock is ticking, and the expertise is on the side 0f the youth – so who knows?

Sociology and reciprocity (1997)

Reproduced on demand. Appendix 3, page 559-68, in my Dr. Philos. dissertation, Gender, Patriarchy and Capitalism – a Social Forms Analysis, The Work Research Institute, Oslo 1997. Original text follows.

– –

Appendix 3 Sociology and reciprocity (1997)

Introduction

This appendix discusses some methodological points of social forms analysis, and some sociological perspectives on reciprocity, including Gouldner’s and Baudrillard’s views. Due to considerations of length, a draft on various sociological traditions concerning reciprocity (Simmel’s reciprocality, Weber’s rationality, Parsons’ normativity, action-theory and life-gift views, neo-positivists, Habermasianists, materialist feminists, etc.), has not been included here.

Structures, reciprocities and life worlds

During the 1980s it became common to criticise structuralist and institutionalist views, and the radical 1970s structuralism especially, for neglecting the individual actor, to the extent that ‘structure’ itself became disreputable. It is still often argued that a structural view, must include an assumption that individuals are ‘determined’ and can do nothing to change their world (Skjeie 1992:19). I disagree with this view for several reasons.

Much of what came into disrepute as structural determinism was simply another line of action, usually a more radical one than the ones favoured by the individualist critics. This is fair and well, but it concerns two lines of action, not inaction versus action.

No amount of structural theorising by itself negates or opposes individual action. The argument that there is rough terrain ahead does not by itself translate into an argument that people should not attempt to move forwards, or are not doing so already. That idea is comparable to opposing diagnosis to treatment as if contradictory in principle. Structural views must be evaluated on their own grounds. What do they tell us of society’s structure? Is this true, or is it not? Their capabilities for interpreting individual action is a different issue. The diagnosis may be bad, the treatment good, or vice versa; we cannot directly infer one from the other, even if there is often a correspondence.

A structuralist view easily becomes misleading if not connected to a view of institutionalisation and interaction. The link between individual existence and societal structure becomes meaningful and comparatively directly observable mainly on the institutional level, or what Robert Merton (1949) called the ‘middle range’.

It may be objected that structural categories are also easily static categories. In view of the radical structuralist and critical theory of the 1960s and 1970s, the problem was not that it discouraged action, but that it did not sufficiently focus on the responsibility of the individual and on individuals’ actions, pointing to its lack of emphasis on democracy in this and in many other related respects. Yet nothing of this does away with social structure as such.

Analyses oriented towards individual action always presuppose some concept of interdependency; if this is not stated, it usually means that a market-rational or utilitarianist framework is brought along as a matter of course. In other variants, especially mid-century sociology, a normative framework with more redistributive aspects lie in the background. Whatever the case, these must be made explicit, and this issue becomes acute in gender studies, where the conflict, precisely, is often one of different reciprocity conceptions. So actor- and individual-focused methods may certainly be of help explaining gender-related actions, but less so if structural constraints, including reciprocity patterns, are ignored.

Structure by itself, in the sense of the ‘structuralist school’, is not a main issue in social forms analysis, which instead is process-focused and activity-oriented, using ‘code’ and structure categories mainly in that context. By investigating transfer and reciprocity patterns in social interaction, the focus is shifted towards the background foundations of institutions, not as a matter of (natural) stasis but as historical processes. This is combined with minimalism regarding supposedly universal categories, since these are always to some extent misleading and easily projective. While the ‘kernel code’ should be as small and generic as possible, theories can be seen as ‘modular’, made up of modules around this kernel. Why should the kernel be small? Social life has a bad habit of departing from any pre-given category or notion.

This approach is very different from the traditional structuralist view, including much critical theory and many interpretations of Marxism. It is the social and historical engagement of a category that mainly points to its usefulness, and not its pretensions towards universality, which is usually where the ideological aspect comes into it. True, even a minimalist view, in the sense described, contains some pretensions in this regard, as discussed in the text (chap. 7), yet the emphasis and line of approach is different. The idea is not to find a holy grail of conceptuality, everlasting categories that stand above life and history. It is not to ‘subordinate’ current gender or other phenomena into some larger, enlightened ordering of gender, as a subcase. On the contrary, an ‘extensional’ or contextual interpretation of social concepts is used precisely to move beyond that stage.

What we often find, then, behind a separated higher stratum of abstract reasoning, performing a work which is basically of ‘heroic’ nature, claiming eternal truth-value, is masculinity ‘neutralised’, abstracted, or sublimated, with a real life pattern and social context behind it. Unlike some feminists, I am not saying that nothing good comes out of this, and unlike ‘total’ relativists or theoretical nihilists, I am not saying general categories are simply fictitious. On the contrary, we can appreciate their true generality better by moving beneath their abstractist layer, uncovering the engagement, concern and struggle that usually lie behind it.

Whereas traditional materialists argue that individuals are dictated by material circumstances and interests, the social forms approach to materialism is more complex. Social life indubitably is material, yet the material as such has no pre-eminence in this framework. Instead tradition or culture in the wide sense of ‘past results of human activities’ is granted influence, since it tends to pattern action, or create a meta-layer of precedents. This ‘sociomaterial’ (as Dag Østerberg calls it), however, becomes more or less effective through its ability to link up with current processes. It has no weight on its own, and the same is the case with ideas. We do not stay within the materialist / idealist framework of discussion; rather, this whole framework is interpreted as part of a specific social form context. Although material circumstances are important on a general level, not much can be said, or inferred, at that level, due to its ‘abstractism’.

The ‘elemental’ logic of this link is the transfer, not narrowly defined as the transactions necessary for life, or as distribution, but as a wider concept of the connecting of past life for creating present and future life conditions. The entities transferred are past life in fragment form, through a certain ‘code’. Many social contexts can be understood by examining these transfer codes as well as the attempts to transcend them; what they mean, how they work, how they act together, what is pushed upwards or ‘sublimated’, ‘abstracted’, and what is hidden below.

Therefore, the present text might also be approached from a methodological individualism angle. I start with not only with individuals, but with individuals doing their best to be or become ‘really individual’, to get out of the queue of anonymous existence, for the purpose of loving one other person uniquely and personally. Yet all this individual uniqueness, brought together, ‘publicised’ in partner selection patterns, has not straightaway taken off from society. It remains dependent on structural constraints, being significantly influenced both by exchange patterns, which is what people commonly start off from, and by gift and sharing patterns, which is where they want to go. “Gender”, in this perspective, is what people make out as, in a certain setting where choices are limited and structured in a specific reciprocity context, extending into a cultural and societal cycle of opposed reciprocities, what I call a ‘polarised’ structure.

Social forms analysis does not conceptualise life patterns or ‘life worlds’ as virginal areas or petit-bourgeouis zones about to be intruded on by society’s systems, like some currently popular paradigms. Once more, an idea which is ‘latently’ misleading becomes acutely awkward in the gender area. Jürgen Habermas’ portrayal of a life world outside society – besides being an updated version of the Victorian theme of the home / the woman as ‘moral elevator’ for the man / the market – tendentially absolves individuals of societal responsibility. I also find that it represents the neutralised masculinity theme introduced above. Although indirectly quite indicative, therefore, of a certain gender-related development, it remains the case that Habermas’ theory (e.g. Habermas, J 1989) is somewhat ‘blind’, to put it mildly, on that point (for a Marxist critique cf. Postone, M 1993:235; for a defence cf. Bohman, J 1989; Carleheden, M 1994). In some feminist views (e.g. Fürst, E 1994:164) the colonisation of the life world is another term for ‘the increased dominance of exchange value’. Others (e.g.. Carleheden, M 1994) find ‘the paternalistic state’ in this role. Whatever the case, it is ‘out there’, and it is precisely this kind of theorising that makes it anti-feminist in tendency.

Life worlds change with social worlds, and are as much a part of the latter as any ‘macro’ phenomenon of society. Families and factories, as we know them, in their modern sense, were created together, closely interlinked, in tandem. The idea that human nature stays apart, as a subject to be located in some ahistorical realm, while society changes historically, is one main barrier that hinders an understanding of how they change together and how they influence each other. Society never ‘intrudes’ in this sense: it is there all the time.

Functionalist sociology and Gouldner’s ‘norm of reciprocity’

One of the main contributions to the sociological understanding of reciprocity come from Alwin Gouldner’s well-known papers on the subject (Gouldner 1975). Before I discuss these, something should be said of Gouldner’s general approach (or his approach until the mid-1970s), and the way it differs from a social forms approach. Today, functionalism is often criticised in an ‘as such’-approach, as if functionalism as such lead research astray; yet I believe that a functionalism like Gouldner’s may often be more insight-giving and imaginative than the later alternatives (that in fact also often turn functionalist when they try to explain anything). It often precisely where I disagree with functionalist explanation that I find it most fruitful in this wider sense. For example, in the case of Gouldner, society is basically explained in terms of social norms, which is not my view. Yet one cannot fail to see that this is where his associations become most interesting, here he is free, so to speak, on his home turf. He is often better discussing the normative level of reciprocity (or the transference level in my terms) than he is discussing reciprocity (the transfer level) itself.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Gouldner’s radical functionalism advocated a critical, political, humanist sociology. Gouldner argued against value-free, positivist theories of science (1975:3pp.). Yet his method is meta-positivist in the sense that even if it arrives in a critical or radical position, the approach itself in major respects does not differ from that of the positivists. Consider the following statement:

“Generically, the norm of reciprocity may be conceived as a dimension to be found in all value systems [by which he means normative systems] and, in particular, as one among a number of ‘Principal Components’ universally present in moral codes. (The task of the sociologist, in this regard, parallels that of the physicist who seeks to identify the basic particles of matter, the conditions under which they vary, and their relations to one another.)” (Gouldner 1975:242).

The method of Gouldner (and of his opponents) is brought forth here.

- There is the implication, first of all, that the social is not what is changing, but that which does not change. Change is secondary, a dependent variable or property of the social, after the sociologist has identified patterns that exist above the level of historical change.

- Since the social, in this concept, does not change, it is not principally distant from, or different from, that part of the social that the sociologist happens to be in. The text is not to be read as an expression of its real context, the actual context of the sociologist writing it. Instead, the sociologist has an immediate conceptual access to a room of unchanging, universal traits, an as such-space which is beyond historical time and space. Certainly, for Gouldner, more than for his opponents, sociological theory reflected the conditions of the sociological theorist; this was one of his main points. Yet it remains a very limited ‘reflection’; it is not a property of the basic epistemology, but rather the ways in which it is used. Therefore the debate was not about the as-such-space itself, but rather one such space posited against others, like Parson’s view of normative congruency (one universalist space) as against Gouldner’s view allowing more conflict, discongruence, dysfunctions, etc. (another universalist space).

I believe that this presumed immediate access has been a main temptation for many sociologists, a conceptual ‘stairway to heaven’. As argued, it is not just a false-leading temptation, but also often one that makes their work interesting reading. The results may in fact be more interesting and indicative when the sociologist tries to universalise, say, American middle-class 20th century values and lifestyle, than when she or he is at pains not to do so – and often for the reason noticed; one is ‘securely grounded’, some imagination is therefore allowed also. Yet there remains a basic problem with this approach. There is a false security involved; the method does not require a continuos self-correction and critique as part of the process towards approaching more general traits of social systems. Gouldner, for example, does not conceive of the sociologist looking for basis-traits of people, like the physicists looking for basic particles, as reflective of something beyond itself, as indicative of a particular context of people, and those about to ‘know’ them; rather it just is, as the way to scientific knowledge.

- Therefore Gouldner does not feel the need to ask himself how it is that this method – which even at the face of it is somewhat awkward, since people change all the time – seems true and natural. There are no checks in this kind of theory, between the real context, and the assumed universal context. This kind of checks, signals of when to stop, to reconsider, is what social forms analysis tries to contribute to, by extending a critical approach, by building on the best of Marx’ value form theory but also going beyond it, by incorporating gender and a broader, multidimensional participatory view.

- When considering the norms of reciprocity and beneficence, therefore, Gouldner’s method does not tell him, first, to carefully trace the modern connections of his analytical apparatus; there is no idea that what seems most universal, on this horizon, may be, precisely, the least universal part of it, due to the abstraction process of capitalism or for other reasons. So, for example, Gouldner in discussing the reciprocity relationship argues that whether the donor gets the economic equivalent back is simply an empirical question (1975:243), failing to see that this question lies at the back of his own analysis, indeed that it often appears as the greater ‘anxiety’ to which the analysis is an ‘answer’, in the sense of ‘symptom’. Gouldner’s method does not lead him to question the commodity form framework of his own sociological imagination, before dealing with presumably ‘other’ kinds of relations – even if he would probably agree to the centrality of the commodity in the modern world.

The idea that societies are ‘value systems’ generated by norms is idealist. Yet Gouldner might as well be a materialist arguing that norms are governed by material factors (and in a way he is, since in functionalist theory norms are generated by ‘system needs’ that are at least semi-material). It is not what or who governs, but this governing of social life itself which is the basic issue.

- Thereby, also, the political aspect of meta-positivism comes to the forefront, as a science of variation within the status quo, or as some would say, co-opted change, allowing endless transformations within the larger stasis. Whereas people live their lives, i.e. change, the sociologist is the one whose ‘direct access’ turns into a power access, an access to the powers that be, that hinders change. The ideological, legitimatory ‘function’ of meta-positivist sociology thereby becomes clearer, as the ‘universal’ space of discussion, surprisingly, also turns into the ‘power place’ of discussion.

I shall turn to Gouldner’s portrait of reciprocity, which he sees as a norm existing together with two other norms, one of beneficence, and another of moral absolutism or supernatural sanctioning, which primarily enforces the two former norms. The three, he believed, are present in various degrees in all social systems. From this perspective, he criticised Mauss for overlooking ‘the norm of beneficence’ and for not distinguishing between the intention of the donor, which may be beneficence, giving something for nothing, and the common consequence of giving, a reciprocal relationship of ‘something for something else’ (1975:298-9).

The history of how Mauss and the anthropologists after him changed a ‘giving’ perspective into an ‘exchange’ perspective on the gift, is highly interesting, as Gouldner (1975:298) retells it:

“Bronislaw Malinowski had, in his earlier work, spoken of the gifts given by a husband to his wife as ‘free’ or ‘pure’ gifts. Mauss, however, in re-examining Malinowski’s own data, had noticed that, in due time, some return was in fact given the husband: women returned their husbands’ gifts with sexual favours. Consequently, said Mauss, the husband’s gift could not be called ‘free’ or pure since it did bring a return.

In his own Essay on the Gift, Mauss stressed that there is a culturally pervasive rule which requires that those who accept a gift must later return it. He therefore concluded that what had appeared to Malinowski to be a case of beneficence was, in reality, a case of reciprocity. Interestingly enough (..) Malinowski accepted Mauss’ criticism (..), the only party that might have suffered from this entente cordiale was social theory. [Gouldner goes on to comment on a scientist agreeing to “deeply dubious” criticisms of his own work as if that was “a very unusual case”]. Basically, Mauss had correctly sensed the functional interconnection between beneficence and reciprocity; but he failed to see and to work out the conceptual distinctions between the two.”

One would agree with Gouldner that this criticism is deeply dubious, even if it is not at all unusual that conventions, power, etc., make researchers turn their back on earlier discoveries (cf. Barry’s paper on Otto Rank). Moreover, the whole case of the enlightened liberal gentlemen’s agreement on this point – i.e. a point where women make pure gifts into something more merchandise-like, by their returning ‘sexual favours’, is probably better explained by the modern context of these men and their theories and their views of women and sexuality, than anything else. Those who seek, will find – in a love relationship there is of course ‘returns’ of all kinds; anything can be seen as a ‘return’. If Gouldner is right, giving as the logical verb of ‘gift’ was turned into exchange due to this ‘minor matter’ of women’s ‘sexual favours’.

Gouldner’s (1975:277) portrait of the relationship between the norms of reciprocity and beneficence is of relevance for the distinction between transfer and transference. After describing various system-enhancing functions of the norm of beneficence (turning “domination into hegemony” and “merely powerful strata into a legitimate elite”; creating “outstanding obligations” and “social debts yet to be discharged”; preventing the “squaring of accounts” and “vicious cycles” of retaliation; and serving as a starting mechanism or “ignition key” for the “motor” of reciprocity), Gouldner notes the paradox that

“there is no gift that brings a higher return than the free gift, the gift given with no strings attached. For that which is truly given freely moves men deeply and makes them most indebted to their benefactors. In the end, if it is reciprocity that holds the mundane world together, it is beneficence that transcends this world and can make weep the tears of reconciliation.”

This describes a special type of transference, in a particular transfer context, yet it serves to illustrate the general principle that people are indeed moved by transferential patterns beyond the transfer itself. It is not the act of giving, by itself, which is special in the case he discusses, but the larger meaning given to it. The transference level of analysis points to the fact that this meaning is always there, even when there are no ‘tears of reconciliation’.

Although Gouldner’s writings on reciprocity went beyond the ‘exchange’ perspective of Mauss and Malinowski, he is still focused on one main question, namely what the gift can return, what it will bring back. The free gift, as we just saw, can be the one of the highest return. As mentioned Gouldner does not address how such assumptions are part of a specific moral universe. He discusses reciprocity on an implicit background of commodity exchange, a world of scarcity and individual actors whose obligations are centred on the dyadic reciprocity relation. The natural consideration of a donor, therefore, is what he gets back, if only in terms of the further effects of beneficence. Yet this may be a very secondary consideration if the donor’s context is, indeed, that of a gift system, a redistributive system, or some combination of the two. In that case, the ‘receiving back’ function is often already taken care of by an elaborate set of rules that ensures, for example, that the donor anyway receives his part of the daily consumption, for example as part of the sacrificial offering which is ‘given’ to the deities and yet mainly consumed by the sacrificers.

This is also the reason why Mauss’ presumed universal rule, “that those who accept a gift must later return it” (op.cit. 298), is true only of some types of gifts; in early Greek traditions, for example, we find gifts that should be passed on to a third party (following a ‘not to touch the ground’ principle, not to be stored), gifts from the far periphery that were not returned, one-way sacrificial gifts, and much else, that was object to other rules. Westermarck’s more cautious observation (quoted on p. 242) that “to requite a benefit (..) is probably everywhere, at least under certain circumstances, regarded as a duty” seems more correct. The point, however, is that this ‘requital’ does not need not be in the form of a return, or conceptualised in that manner, and it does not need to be directed towards the original donor(s).

Gouldner does admit that the “reciprocity complex” is more extensive than the part of it that he examines, “the generalised norm of reciprocity” (op. cit. 246). Yet within this framework his reciprocity relationship resembles a ‘delayed commodity exchange’, with a loose and rough account rather than precise reckoning. It remains within a universe where the stress is on the direct relationship, donor to recipient, A to B, and not this relation as one of many others in a socially organised whole. In the latter case, “receiving back” is often irrelevant, since there is a whole string of gifts and redistributions, and a “politics” which is far more complex than this question would imply. A gives to B, B to C, and so on; simultaneously there may be a redistributive relationships between them; it is easy to see that such a complex pattern of interaction – beyond the dyadic logic of commodity exchange – also calls for far more complex strategies a considerations. The premise of scarcity, and the connected idea of utility (in a reciprocity relationship, Gouldner believes the self’s “right to exist is dependent upon and must be continually renewed by its demonstrated utility” (1975:269)) aren’t independent of the social form and cannot be taken as a priori ground rules.

If the transfer relation is often a dyadic relation between two parties, we may say that the transference field relation is in principle triadic. And that is even a poor way of stating it, for it is not only that a transfer relation A-B is here conceptualised in relation to some third matter C, but more, that the whole dyadic relation is reinscribed within a larger and much more complex relationship C. “Reinscribed” seems a fitting word here, for the dyadic character of many transfers may indeed be seen as “expressions”, or fragments, of a larger whole. This redefinition in terms of larger matters do not imply that transference is necessarily a more abstract level (chap. 7); it is not necessarily the case that A and B become ‘carriers’ of the larger matter C (and appear as Ca and Cb); rather it is a more general and embracive level, encompassing much more complex social relations. The psychodynamic connotations to “transference” once more is of relevance. The transference level, which Gouldner places (in the case of beneficence) on the level of ideals, transcendence, art etc. may be compared to the way in which daily-life transfers are reinterpreted in dreams – imbued with more or less mysterious meanings that are always there in a very real and effective sense. The transfer may be seen as an artificial insulation from this wider and more complex ‘meaning universe’, recreating it through fragmented actions.

As a consequence of the utilitarian and abstractist framework, Gouldner’s analysis of reciprocity does not really bring out the differences of many reciprocity forms and the commodity reciprocity form (and between the former). His idea that the norm of reciprocity is founded on egoism (p. 245f.) illustrates this. Egoism, we are told, exists everywhere, to the extent that “there can be no adequate systematic sociological theory which boggles at the issue”; Parsons is credited with squarely confronting “the egoism problem”. Beneath these manly stances we find the idea that the egoism of American middle-class men in the 20th. century is the same (“the egoism problem) as what can be found elsewhere. Reciprocity, therefore, is a way to “control egoism”. Yet this is a solution in search of a question, which is not raised, a larger questioning of the whole framework of analysis, which is, “why is it that the actors, whenever nothing else is said, is attributed with commodity form logic of action”. Like Bentham’s idea of the larger benefits of the market, Gouldner finds “altruism in egoism, made possible through reciprocity” (246). The commodity background of Gouldner’s reciprocity also shines through in his treatment of the actors as individuals, so that even if the possibility that they might be groups is mentioned (“reciprocity institutes obligations between individuals (or groups)”, p. 282), this is not explored, and we are left with the portrait of lone actors, as in a market setting. Further, this explains Gouldner’s historical belief that the “norm of beneficence crystallises and develops historically in polemical reaction against the norm of reciprocity”, with the Church’s polemic against rent and profit in mind (282-3). As in market exchange, “the crux of action under the norm of reciprocity (..) [is] the prior classification of self and others into latent debtor-creditor roles” (288). No wonder, therefore, that when Gouldner comes to consider the possible dysfunctions of reciprocity, we meet “dyad-centrism” and the tendency “to break down in the direction of utilitarian expedience” (289).

Gouldner’s and Mauss’ stress on the return of a gift is not a universal rule, but rather one which is true in special circumstances. In fact there is a contradiction between the two main rules of the reciprocity relationship, as portrayed by them – first, that giving represents power, that it places an obligation on the receiver, and secondly, that a gift has to be returned. The failure to see this contradiction stems, I believe, from the ‘scarcity economy’ implied in the background of gift giving. In a modern setting, ‘resources’ by implication are privately owned resources; if an individual ‘has’ resources, she or he can do whatever is pleased with them. The problem, therefore, is one of ‘scarce resources’. This line of thought, as argued in chap. 13, although not purely a modern idea, is nevertheless mainly part of the utilitarian modern framework, presupposing a split between economy and the household, human and non-human resources, and a needs being split off from the main means of livelihood.

Gouldner’s framework may be misleading not only in non-modern contexts, but also, below the surface, in the modern world. This, as I said, already follows if one examines the relationship between the two rules of Mauss. The first rule does not say that the donor is ‘at a loss’ for having given something away; on the contrary – and this is one main strength of Mauss’ analysis in The Gift – having given something away often places the donor in a position of power. And if that is true, the last thing the donor may want would be to have the gift returned, since that would mean the loss of this power. Recieving a gift, therefore, as Mauss amply illustrates, often means coming under the influence of the donor, or into a position of gratitude which means serving the donor. It is often precisely by giving gifts that can not be returned that the rich or powerful exert this kind of influence. In this context, the problem is not the modern problem of ‘scarce resources’. There are no resources of this kind around – things ‘as such’, awaiting private ownership and use. The problem, instead, is one of ‘resource’ and ‘influence’ being interlinked, and therefore, often, how to avoid coming into contact with them. Not scarce resources, but an abundance of ‘resources’ in the sense of power spheres, or zones of influence, ‘centralities’ with dangerous gravitational force. Consider the world of the Odyssey – not only the Sirens, but most of the creatures and places the Greeks encounter have this background dangerous ‘centrality’ which means the travellers will easily get stuck there. It is true, in a very wide sense, that this may be seen as a confirmation of Mauss’ second rule, since staying under the influence of the donor, doing service to the donor, may be seen as a way of returning the gift. Sometimes this is also explicit in the arrangement, like the service to be performed by the in-marrying male (like Jacob in the Bible) before he retains or is granted his full rights. But there remains the important fact that the main wish of the donor, and a main point of gift relations, may be precisely that the gift is not returned. In many gift systems, the importance of this kind of gift is primarily as an entrance ticket to a different, internal, system; one of redistribution. Here, also, the point is seldom to ‘pay back’, and not even to ‘stay in debt’. Rather we may say that these are ‘dependency resources’; they do not exist in the modern form of freely owned, independent things. Accepting them means accepting the dependency. “How can I ever pay you back” may therefore be translated to “how can we / I get out or keep out of this relationship”.

This is even more clearly illustrated if we consider the opposite case, where a person accepts something as a gift which is not ordinarily seen as a gift. This is often a fairy tale element, as in the Norwegian stories of the Ash lad (Askeladden), who unlike his older brothers Per and Pål listen to poor people and take note of seemingly insignificant things. The Ash lad ‘lets himself be given’ things like the advice of an old woman, and much similar, whereas his brothers hasten on towards fame and success. This makes him an adventure hero. By accepting these unworthy things as gifts, he places others as worthy, as donors, and the main idea here is not the one that the gift must be returned, but that the acceptance of a gift is by itself a greater gift, a ‘meta gift’, on the transference level.

Baudrillard on gifts

In a polemic against the modern idea of gifts, Baudrillard (1993:48) writes:

“The gift, under the sign of gift-exchange, has been made into the distinguishing mark of primitive ‘economies’, and at the same time into the alternative principle to the law of value and political economy. There is no worse mystification. The gift is our myth, the idealist myth correlative to our materialist myth, and we bury the primitives under both myths at the same time.”

This is partly correct, only that Baudrillard fails to state that there is also something beyond these myths in the studies of gifts. He then goes on to construct his own version of a gift universalism:

“The primitive symbolic process knows nothing of the gratuity of the gift, it knows only the challenge and the reversibility of exchanges.” I take issue with the subject here, the ‘symbolic’ that knows this, but not that, etc., which I think belongs more to Baudrillard’s context than that of his ‘primitives’. Surely gratuity, as much as ‘challenge’, even if not in its modern form, is present in most gift systems. He goes on to compare the idea of giving, one-sidedly, with the idea of stockpiling capital, a not entirely successful comparison, and then goes on to say:

“The primitives know that this possibility [of a one-directional relation] does not exist, that the arresting of value on one term, the very possibility of isolating a segment of exchange, one side of the exchange, is unthinkable, that everything has a compensation, not in the contractual sense but in the sense that the process of exchange is unavoidably reversible. They base all their relations on this incessant backfire (..) whereas we base our order on the possibility of separating the two distinct poles of exchange and making them autonomous. There follows either the equivalent exchange (the contract) or the inequivalent exchange that has no compensation (the gift).” (Baudrillard 1993:48-9).

Surely the difference – especially for a postmodernist upholding this very concept – between ‘primitive’ and capitalist exchange is not just that capitalism inserts artificial breaks where the other just sees one connected process. The two forms of ‘exchange’ are different in kind. Modern thought does not only ‘isolate’ moments or polarities of exchange that the ‘primitive’ sees in connection; modern capitalism inserts another kind of process altogether. This is elementary. Baudrillard is quite right that the modern analysis of reciprocity, as discussed in the case of Gouldner, tends to isolate ‘segments of exchange’, yet these are segments of modern exchange, which accounts for some of these theorists’ problems with grasping its alternatives, their anxiety over the ‘return’ on the gift ‘outlay’ and so on. It is not exchange as such.

Here and elsewhere in Baudrillard’s writings, and also in Lyotard’s, we are first presented with a massive condemnation of capital and / or modernity, as in this case, only to be presented, later, to a highly abstracted, universalist idea of this very capitalist exchange that one was out to abolish, usually couched in symbolic, referential, significal, or some other term that mainly serves to make the analysis seem deeper than it actually is. I appreciate that Baudrillard tells us that the ‘primitives’ do not think of the return of gifts in a contractual manner, yet he does so only in order to argue, in plain words, that to the ‘primitive’, thinking in terms of returns is natural. It is always there. ‘They’ build all their relations on it. Yet this is a ‘white man’s thinking’ as good as any, not very different from the idea of the ‘primitives’ as capital accumulators and the like. This kind of turning-around can be found in other contexts of Baudrillard’s also, for example in the analysis of seduction, where the supposed transcendence of exchange and other stale principles of political economy (etc.) is postulated only to be replaced with a seduction that under closer scrutiny turns out to be a system of exchange, exchange in the modern, ‘banal’ fashion. In Lyotard’s (1987) The Postmodern Condition, after a condemnation of the meta-narratives of modern science and declarations about how postmodernism is supposed to change all that, we are back to the old terrain of a game theory of social interaction.

A recent plan at the Leeds Becket University to close down their Centre for Men’s Health has created discussion, and even a petition, among researchers. I have joined it. What is needed is a follow up of this research, not a close down.

My own research shows that there are large, but so far not so much realized health benefits for men as well as children and women in terms of gender equality. These benefits emerge as clear macro trends, as well as in survey and interview studies. Other recent studies have strengthened this picture.

Not only are the health outcomes for men more positive in gender-equal countries, with gender equality as an independent factor across e g income level and income equality. Also, the social perception of men, according to experimental psychology, is more favorable – men are seen in a more positive light, in more gender equal countries.

See Holter, Øystein Gullvåg 2014: “What’s in it for Men?”: Old Question, New Data. Men and Masculinities 17(5), 515-548; Krys, Kuba, Capaldi, Colin, et al 2017: Catching up with wonderful women: The women-are-wonderful effect is smaller in more gender egalitarian societies. International Journal of Psychology, 2017. DOI: 10.1002/ijop.12420

The petition is reproduced here:

Researchers Protest against Shutdown of

Leeds Centre for Men’s Health

It is with dismay and concern that we have learnt that it is planned to close the Centre for Men’s Health at Leeds Beckett University in August 2017. This is a huge setback not only for gender studies and critical research on men and masculinities, but for medical, sociological and psychological research as a whole. The Centre has a very high reputation on the European level and beyond.

We have collaborated in very fruitful ways with researchers in the Centre on the issues of men’s health and its connections to gender equality, violence prevention, and the enhancement of well-being for all genders. The Centre’s fantastic work on the Report “The State of Men’s Health in Europe” was ground-breaking: for the first time, data on men’s health in all European countries were analysed in a comprehensive and comparative way. Its results show the high costs that some forms of masculinity, men’s lifestyles and the lack of care bring to men themselves.

We gather that the reason for the closure is that the University seeks to restructure on economic grounds. Thus, the benefits of work of the Centre for Men’s Health, and indeed its overall social and economic value seem to be underrated. Indeed, even seen narrowly in these terms, its important work brings economic and cost savings for the wider society, the city, region and community, public services, businesses and civil society well beyond the University.

There are many good reasons to keep and develop the Centre for Men’s Health: Men’s health issues are about to become not only more recognized, but also more relevant. They are not only related to health itself, but to gender and gender (in-)equality in society (also because of the impact of men’s poor health on women and children), to social innovation and to social development. Moreover, research has revealed a need for cross-disciplinary cooperation on methodological development, for example in terms of improved health variables in other research, and vice versa, in terms of improving health variables and indexes from gender and gender equality studies.

The Centre has proved to be an excellent partner in all these discussion and areas of research. We hope that there will be ways to continue its work. We ask the representatives of Leeds Beckett University to revise their decision and help to sustain the work of the Centre for Men’s Health!

June 22, 2017

Dr. Paco Abril Morales, Girona. Dr. Gary Barker, Washington DC. Mag.a Nadja Bergmann, Vienna. Dr. Marc Gärtner, Berlin & Graz. Professor Emeritus Jeff Hearn, Ph.D., Helsinki. Professor Dr. Philos. Øystein Gullvåg Holter, Oslo. Dr. Majda Hrzeniak, Ljubljana. Dr. Ralf Puchert, Berlin. Mag.a Elli Scambor, Graz. Dr. Christian Scambor, Graz. doc. PhDr. Iva Šmídová, Ph.D, Brno.

Four news from the research front line…

1

The International men and gender equality survey (IMAGES) has recently been made in four Arabic countries (Egypt, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine). The IMAGES survey model, developed from 2009 onwards, is partly based on the Norwegian model in the 2007 (Likestilling og livskvalitet – Gender Equality and Quality of Life) survey, adapted to international use especially in the south world, now further developed in an Arabic version. The Economist writes about the study:

The study can be found here:

2

IMAGES has developed the original Norwegian model internationally. At the same time, it has been developed in a European context.

The first results from a Polish-Norwegian project (Gender equality and quality of life) are now published. A representative survey was made in Poland 2015, combined with qualitative research. The aim was not just to address the most pressing issues of men and masculinities (like IMAGES), but to improve the general mapping of gender in/equality in society and culture. The model was adapted to the more “gender conservative” (in some ways) context of Poland. Two books will be published from the project. Now, the “European blueprint” and “guide” have been published. This is a proposal for a European-wide follow-up study, based on the Poland/Norway testing.

The first results from a Polish-Norwegian project (Gender equality and quality of life) are now published. A representative survey was made in Poland 2015, combined with qualitative research. The aim was not just to address the most pressing issues of men and masculinities (like IMAGES), but to improve the general mapping of gender in/equality in society and culture. The model was adapted to the more “gender conservative” (in some ways) context of Poland. Two books will be published from the project. Now, the “European blueprint” and “guide” have been published. This is a proposal for a European-wide follow-up study, based on the Poland/Norway testing.

http://www.geq.socjologia.uj.edu.pl/en_GB/blueprint

The first book has just been published, describing the the project and the new research developments.

https://www.peterlang.com/view/product/25785?tab=toc&format=HC

The second book, with detailed Poland results, will be published soon.

3

Other research fields and groups are starting to pick up the results, and develop the gender equality and masculinities dimensions in their own ways. This includes an international experimental psychology study:

Krys, Kuba, Capaldi, Colin, et al 2017: Catching up with wonderful women: The women-are-wonderful effect is smaller in more gender egalitarian societies. International Journal of Psychology, 2017. DOI: 10.1002/ijop.12420

The results indicate that the perception of men is more positive in relatively gender-equal countries. In a related experimental study, the researchers find that threat and vulnerability (male role pressure) lowers men’s support for gender equality:

Natasza Kosakowska-Berezecka, Tomasz Besta, Krystyna Adamska, Michal Ja´ skiewicz, Pawel Jurek, Joseph A. Vandello 2016: If My Masculinity is Threatened I Won’t Support Gender Equality? The Role of Agentic Self-Stereotyping in Restoration of Manhood and Perception of Gender Relations. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 17, 3, 274 –284

In another new study, in the US, researchers investigated the role of the “zero sum perspective” on gender equality – the idea that men will lose what women gain, in terms of gender equality. The results show that social dominance and sexism factors are linked to the zero sum perspective, and that men endorse this perspective more than women. Cf Joelle C. Ruthig, Andre Kehn, Bradlee W. Gamblin, Karen Vanderzanden, Kelly Jones 2017:

When Women’s Gains Equal Men’s Losses: Predicting a Zero-Sum Perspective of Gender Status. Sex Roles 76, 17-26

4

The internationally renowned masculinities researcher James Messerschmidt gave a presentation of “revised” hegemonic masculinity theory, at a well-visited seminar arranged by the Centre for Gender Research, University of Oslo, May 3, titled

Going into the theory development in depth, Messerschmidt described how it has led to a more nuanced, open view, which is complex, but also more precise than the sometimes “vulgarized” versions of the theory. This was followed by critical and constructive debate, with students as well as senior researchers participating. A summary and comment on the seminar, by professor Hanne Haavind, has been published at the center’s web site:

http://www.stk.uio.no/forskning/aktuelt/aktuelle-saker/2017/gjensyn-med-hegemonisk-maskulinitet.html

For many years now, we have heard how men do this and women do that.

Men and women are different.

For example, men are more violent than women.

Only recently has research introduced gender in/equality as a control variable, regarding these proclaimed gender differences.

The results are dramatic.

Introducing the gender equality variable unsettles much of what we think we know about gender.

For example:

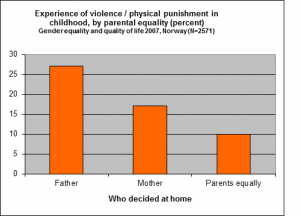

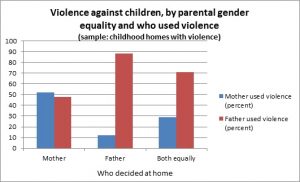

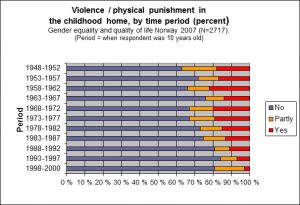

In the 2007 “Gender equality and quality of life” survey (in Norway), almost 2800 respondents answered questions about their childhood home. During the time of their childhood reports, the rate of violence against children generally became lower.

Across this period, gender equality, more than gender, influenced the chance of violence against children. “Who decided at home” (wh0 had the final say) was used as indicator of gender equality.

Across this period, gender equality, more than gender, influenced the chance of violence against children. “Who decided at home” (wh0 had the final say) was used as indicator of gender equality.

Gender inequality, even more than gender, influenced the chance of violence against children.

Father-dominated homes had almost three times the rate of violence against children, compared to gender-equal homes, in the 1940-2000 period covered by the study. Women-dominated homes were in the middle. Gender-equal homes, where the parents decided equally, had the lowest rate of violence.

Those who decided at home were also the ones most likely to use violence.

Generally, men were more often involved in the use of violence and physical punishment of children, but this varied strongly with the state of gender equality in the home. In mother-led homes, women were slightly more involved than men.

The impact of gender equality remained strong, controlling for education and other social factors.

In most of today’s research, gender equality is not used as a variable – the evidence is at best divided by gender, or it is just presented as gender-neutral.

The above example shows the need to correct that situation. By neglecting gender in/equality, research is missing the true picture.

Recently, a Poland survey has confirmed the basic pattern found in the Norway 2007 survey.

In Poland, also, lack of gender equality among the parents approximately doubles the chance of violence against children. Even if Norway and Poland are different in many respects, including different views of gender, these basic results are much the same.

Violence against children is just one area where gender equality has an impact.

Other areas, more focused in recent research, include education, health, quality of life, social perception and social stigma.

I started my Christmas holiday with some new crime novels. This one, however, got the best of them. By accident I pulled it out from my book shelf, I had not read it since the early 1970s – and it got a hold on me. Much more exciting than the crime novels.

The excitement comes from the real-world historical drama, not a construed plot, from the detail, and from the way the author digests and analyses the detail. There is no doubt, this is a great mind at work. The world would have been a better place, if Trotsky instead of Stalin had followed Lenin, in the Soviet Union. I have critical points too, but for now, my message is just, read it.

How come capitalism does not work out, or only partially, according to the textbook rules of universalist free market competition and meritocracy? How come capitalism even in relatively gender-equal countries has stabilized at a two thirds income rule for women, compared to men? Why is inequality and discrimination still so common in global working life? Starting from practical, everyday experiences, my new book project will focus on the hows and whys of social inequality, especially, what can be known, using gender inequality as a “lens” or focus element. I want to go beyond broad exclamations that gender oppression is “closely linked to” or “intersectional” with other oppression forms like race and sexuality, or that different oppression forms tend to strengthen each other. Sometimes, they don’t. Instead, reduction of one form of oppression is bought at the cost of increase in another form. Current Western gender regimes that offer more gender equality to the upper middle class at the cost of harder ethnic oppression is a case in point. There is a substitute effect. In my book I will highlight the broader structural background of current gender issues, and how the struggle for gender equality becomes important, even if partly overlooked. My text will be critical. I think we have been seriously misguided.

In 1999, professors R. W. Connell, Jorunn Solheim and Dag Østerberg evaluated my research. The main part of their evaluation is presented below.

Competence evaluation of Øystein Gullvåg Holter (excerpts)

“March 1999

“Øystein Gullvåg Holter applied in December 1997 for a competence evaluation as researcher I (professorial level) at the Work Research Institute. On the basis of the application an evaluation committee was appointed in February 1998, consisting of:

professor Dag Østerberg, Oslo

professor Robert Connell, University of Sydney

professor Jorun Solheim, The Work Research Institute, Oslo (WRI)

The recommendations of the committee are unanimous.”

“The evaluation has been conducted in accordance with the WRI rules for competence evaluation. These rules state that the competence level for a researcher I-position shall be comparable to that of a university professor.”

“As a scholar, Øystein Gullvåg Holter has produced an extensive amount of publications. His CV consists of 13 book titles or more extensive publications, and about 90 papers. The overall scope of the entire production is quite remarkable. The work covers a broad field of theoretical as well as empirical research”.

Evaluation of selected publications

Gender, Patriarchy and Capitalism. A Social Forms Analysis

“This is Holter’s doctoral dissertation, submitted for the dr. philos. degree at the University of Oslo, october 1997. The thesis is an extensive attempt to integrate a theory of patriarchy with an analysis of gender and economic relations.”

“It is without doubt an important work of scholarship, and probably one of the most sophisticated attempts yet to integrate a theory of patriarchy with the analysis of gender and capitalism. A particular strength is the extraordinary scope of the analysis, the inclusiveness of the theoretical argument, and the interweaving of theoretical analysis with empirical research. It is also a highly original and innovative work.” “At the same time, the dissertation presents several difficulties (..) the work presents itself as too much of an enigma to the reader (..) it is exploring rather than systematic.”.

“The overall impression of the thesis is that of a highly original and inventive contribution to social theory. The work has great potential, and should, given a further treatment in the direction of a more accessible and less all-inclusive argument, deserve wide recognition. The committee can therefore without difficulty endorse the former doctoral committee’s unanimous acceptance of Holter’s dissertation.”

Family Theory Revisited

“The paper is a fine contribution in the genre Holter is very good at – the reconfiguration of a field of ideas, based on an assembly of detailed empirical studies.”

Work, Gender and the Future

“The paper is well-formulated, reads clearly, and shows Holter’s ability to condense and translate complex issues into a clear argument, without losing sight of the intricacies of this complexity.”

Catering for the Oil

“An instructive and well written piece of industrial sociology, which describes and analyses working life and work conditions on Norwegian offshore oil platforms.” “As an integrated study on the structure of work, labour processes and community formation it has great merit, and it also testifies to Holter’s skill as an empirical researcher.”

Men’s Life Patterns (Menns livssammenheng)

“The text conveys stongly the contradictory elements of emotional relations which characterize men in contemporary family/work settings, and nicely complements the more economic focus in other works.”

Authoritarianism and Masculinity

“Strongly confirms the relevance of authoritarianism for contemporary social research, making the paper an admirable case of ’continuity in research’. The paper deserves publication for a much wider audience”.

Conclusion

“Taken together, these texts may be said to constitute the work of an exceptionally versatile sociologist on a high academic level. They document an unusual capacity for intellectual synthesis and mastery of a range of research methods and styles. Through these texts, Holter comes across as a very competent scholar, who combines theoretical brilliance with a deep concern with the practical relevance of social science.”

“A common requirement for awarding professorial competence, is that the candidate should have an academic production comparable to two doctoral dissertations. Even if these requirements are not always taken literally, the committee find that they should not pose any problem in this case. Taken together, the group of publications submitted apart from the dr. philos thesis, make up a body of work that combines the theoretical scope and empirical content equivalent to another ’dissertation’. Added to the doctoral thesis, these works should therefore, in the committee’s judgement, be quite sufficient to confer upon Øystein Gullvåg. Holter the required professorial competence.”

“The committee finds that Øystein G. Holter without doubt meets the specific WRI requirements for researcher I competence, and that he is very well qualified for such a position.”

Oslo/Sydney 8.3. 1999

Dag Østerberg Robert W. Connell Jorun Solheim

(sign.) (sign.) (sign.)