Some pictures revisited

Øystein 14.12.20

I was born in 1952. I remember my early school years as bad. I was mobbed, due to living in a non-traditional family. In the 1950s, having a career mother was enough to qualify for deviance from the norm, and parental divorce did not make it better. Later, I paid back, with a vengeance, not just through my writings, but also in my visual art.

An early influence in my development of drawing and painting, was our teacher Eva Grande, at the primary school (Ullevål skole), who patiently took us along the route to beautiful hand writing, as well as stopping any perceived tendency towards mobbing (she saw just some of it, but that was not her fault).

Learning from her, I started to “beautify” the letters she wrote on the blackboard. I made other sketches as well, which got into a habit, in the more boring lessons of other teachers. Later, I used this technique on other shapes as well, not just letters. Like this outline somewhat resembling a shrimp.

My drawings and paintings were always on a “hobby” level, I never tried to become professional, or make it my living, which was probably wise, given my limited talent.

Hitting back at the mobbers – symbolically – could include pictures like this one, called “Angry man”:

I remember, at school, making these kinds of portraits, a teacher asking “Is this me?”. “No”, I said. I never thought of anyone in particular. I tried to grasp the tendency.

I also tried to picture the conflict itself, e g through a broken heart. Like a space explorer with a strange helmet.

Jorun Solheim: Shakespeare i smuget, John Grieg forlag.

Anmeldt av Øystein Gullvåg Holter, oktober 2020

Jeg tenkte først: dette blir spennende. Så merket jeg, jeg la boka bort. Dette blir for heftig, tenkte jeg. La meg vente til jeg er på hytta, og har tid, fred og ro. I mellomtiden leste jeg meg litt opp. Bare litt. Jeg leste Uncut’s «Ultimate music guide: Dylan», som iallfall er fri for annonser, og gir oppdaterte syn på hva Mr Bob har prestert her i verden, album for album.

Solheim har levert en glitrende beskrivelse av hvordan Bob Dylans kunst, og særlig hans tekster, kan oppleves. Jeg bruker ordet «glitrende» fordi jeg ble grepet, da jeg først kom inn i boka, etter et kapittel eller to. Jeg leste i flere timer, og leste resten neste dag. Kunne ikke legge den vekk.

Og jeg har tenkt på den mye etterpå. Når jeg gjør praktisk arbeid. Noen av Dylans melodilinjer dukker opp i hodet mitt. Jeg husker tekstene som Solheim skriver om fra gammelt av, nynner sangene inni meg, og tolker dem nå på delvis nye måter. Hva mer kan man be om? Det holdt til å beise hele verandaen på hytta i dag. Indre melodier, musikk til arbeidet.

Jeg tenker også på hvordan forfatteren får fram det beste og viktigste i Dylans tekster. Hvordan hun balanserer kunst og resepsjon. Sine egne erfaringer, en personlig ramme fra ungdomstidas møte med Dylan i hans klassiske periode på 60-tallet, uten at dette tar overhånd, men danner en fin ramme om musikken som beskrives.

Det er sjelden jeg opplever en bok om musikk på denne måten. Jeg har lest en god del, selv om mye Dylan-litteratur (et stor felt, nå) er ukjent for meg. Jeg har hørt mye Dylan, gjennom tidene, og regner med at det også er en kvalifikasjon. Jeg har mitt eget personlige forhold, og et stort pluss ved Solheims bok er at hun gir stort rom for dette. Hun er åpen og ærlig og hva hun liker og misliker av hans musikk, og begrunner hvorfor dette er store kunstverk nettopp fordi kunstneren lar oss tolke på vår egen måte. Det er ingen fasit.

Forfatteren er litt eldre enn meg, og alder var faktisk viktig på en nokså spesiell måte, på 1960-tallet. De eldre hørte Dylan som et tilskudd til folk og protestsang, mens de yngre syntes det ble ennå bedre da han gikk forbi dette. Og plugget inn en elektrisk gitar. Solheim og jeg har imidlertid omtrent samme syn på dette. Det begynte med den symbolske vendingen i Dylans sanger. Så kom elektrifiseringen. Dette er vel i og for seg nokså allment godkjent nå – Dylans «klassiske» periode var fra da han startet å skrive sine egne mer «introverte» sanger, og etterhvert tok i bruk rock og el-instrumenter, fram til han måtte ta en tur på landet, det ble for heftig (for å si det enkelt), på slutten av 60-tallet. Med sanger som Hard rain’s gonna fall, Ballad of a thin man, Mr Tambourine man, Like a rolling stone. Solheim bruker mikroskopet omtrent som jeg ville gjort, på de store verkene fra denne tida, som Visions of Johanna.

En «glitrende» bok er ikke bare en bok man er enig i, men noe man har fått å være uenig i, noe man kan bryne seg på. La meg ta noen småsaker først.

Solheim avviser the Byrds versjon av Mr Tambourine man som sentimental. Var den egentlig det? Er ikke ordet kommersiell mer dekkende? Jeg hører ikke så mye sentimentalitet, men derimot et sterkt ønske om å lage noe som var «fengende», en ekte hit-låt. Som den ble. Som solgte langt utover det som hittil hadde vært Dylans fan-skare. Var det dårlig? Byrds ble da vitterlig etter hvert ganske gode Dylan-tolkere (Chimes of freedom f eks) og utviklet seg til et særdeles godt band (hvis i tvil, hør deres live versjon av 8 miles high, på live-albumet «the Byrds»). Så ja, litt mer balanse her, hadde vært kjekt.

I det hele tatt kunne jeg ha ønsket mer referanse til andre artister som utvekslet ideer og noter med hverandre, og litt mindre følelse av at Mr Bob var totalt i en «klasse for seg», King of the hill. Det var han ikke. Det var mange andre would-be-poeter (f eks John Lennon, Jim Morrison), og Dylan var som en svamp, tok til seg alt som var brukbart, fra disse (altså, ikke bare fra americana-røttene som han senere har framhevet). I forhold til Beatles, for eksempel – dette var toveis innflytelse, på midten av 60-tallet.

Solheim skriver et sted at hun forteller mest om tekstene til Dylan fordi hun skriver en bok. Det er ikke en helt god begrunnelse – og heller ikke hovedbegrunnelsen i boka – som er at hun skriver om det hun ble mest opptatt av. Men jeg skjønner hva hun mener. Det er lettere å forholde seg mest til tekstene i en bok, på samme måte som musikken er hovedemnet, på et noteark.

Det er ikke slik at forfatteren bare ser på Dylans tekster og ikke hører på melodiene og musikken. Hun framhever stemmen, hvordan den enten gjorde sterkt inntrykk, eller ble avvist. Solheims små anekdoter fra Dylan-mottakelsen på 60-tallet treffer blink. Jeg opplevde selv hvordan min mor ba meg skru ned lyden på Dylan’s Hard rain, ut fra at hun ikke «orket mer av den stemmen», på 60-tallet. Og jeg husker samme diskusjon på fester. Boka er full av slike treffende referanser til 60-tallets kulturendringer. Det fikk være grenser! Dette var i en periode der langt hår for gutter fortsatt var kontroversielt. Der lytting til Bob Dylan fikk preg av å være «motkultur», et brudd med den herskende kulturen, systemet, eller «the establishment» som det etter hvert ble kalt.

Likevel savner jeg litt mer om musikken og melodiene. Melodiene, særlig. Solheim kunne godt vært tydeligere på å framheve melodienes betydning, når det kommer til «I want you», for eksempel, som har en av Dylans mest fengende melodier. Kunstverket er en enhet (mer eller mindre vellykket) av tekst / sang, og melodi / musikk. Ordene i I want you er for meg tegn på glede, yrhet, ikke bare en stabel av fenomener eller metaforer – når man hører dem som sang, med musikken. Går man bare inn i teksten, og leser ham som poet, blir det for trangt. Om man hører ordene sammen med melodien, gir de en annen – eller la oss si, tredje – mening. De betyr noe nytt sammen. Solheim skriver stort sett bra om dette, boka er ikke en løsrevet «tekstlig» poesianalyse, selv om jeg altså gjerne hadde sett mer om musikken og melodiene.

Dette kan ha å gjøre med at jeg selv var aktiv i kritikken av kommersiell musikk på slutten av 60-tallet, og var med på å grunnlegge organisasjonen Samspill i 1971, som senere la grunnlag for plateselskapet Mai, og en musikkavis, Vår musikk. Vi var motstandere av ensidig kommersialisering av musikken, men samtidig tilhengere av utbredt konsum (av god musikk). En umulig oppgave? Javisst. Tanken var at motkulturen kunne utnytte kommersielle krefter (ikke bare omvendt). Det betydde, for eksempel, at tilmed Paul McCartney kunne skrive en «god nok» tekst, fordi det som teller, er det totale uttrykket, kunstverket slik det faktisk kommer i bruk, ikke bare teksten for seg. Når man tar inn at Byrds’ versjon av Tambourine man vekket gjenklang i tusener av amerikanske hjem der Dylan direkte ikke hadde fungert, blir vurderingen annerledes. Dylan ble selv opptatt av å bidra til samfunnskritisk pop. Forfatteren virker mindre interessert.

Fra en kjønnsforsker som Solheim hadde jeg kanskje ventet en ennå vassere diagnose av Dylan som proto-feminist, «androgynatisk» (for å bruke et begrep for boka Menns livssammenheng), til tider trans, en banebryter i forhold til kjønn. Her har forfatteren mye spennende å si, men ambisjonsnivået er trolig klokelig lagt noen hakk ned. Hun dokumenterer at Dylan var kvinnevennlig og relasjonell i bred forstand og ikke bare kan avvises som mannssentrert eller (av og til) misogynistisk, men hun går ikke så mye videre fra dette. Det tror jeg er realistisk. Det er kanskje riktig at Dylan på sitt beste kan tolkes som forkjemper for en ny kjønnsorden – men vi er fortsatt innen en mannssentrert kultur. Emnet fortjener oppfølging.

Det som blir tydelig, er at Solheim, ved å ha med kjønnsperspektivet i analysen, ofte tolker tekstene på en ny måte. Dette er kanskje bokas viktigste «added value» i forhold til den eksisterende litteraturen om Dylan, som stort sett er skrevet av menn.

Solheim avslutter boka med et drømmekapittel. Dylan kommer ramlende inn i buskaset mens forfatteren sitter under et tre og leser en bok. De prater og samtalen består utelukkende av sitater fra Dylan-sanger. Godt levert. Men jeg blir litt undrende, når forfatteren ender kvelden med å bre over gjesten et teppe, og så gå å legge seg, alene. Mange hadde nok hatt en litt våtere drøm.

Et par videre utfordringer kan nevnes. Det er litt tendens i boka til å teoretisere seg bort fra hovedsakene – men ikke mye. De antropologiske referansene er relevante (og dempet ned) – bra – men hvor mye de egentlig bidrar med, i forhold til Dylans tekster, er ikke alltid klart. Metaforene er bestemte og konkrete – javel – men så kan de også bety forskjellige ting – javel. Som nevnt, dette er ikke tekster, det er del av et kunstverk som kalles «låt», «sang», «track» osv – og analyse derfra kan trolig gi mer mening i bildet.

Boka er personlig vinklet – til en viss grad. En antropolog oppsøker sitt personlige felt. Hvordan er denne grensen dratt? Gjentar forfatteren det hun har opplevd som hovedsaken, ved artisten? Blir hun selv en «masked marauder»? Er boka litt mystisk?

Jeg synes den forblir litt uavklart, uten en klar slutt (men ikke mystisk). Uavklart for eksempel fordi forfatteren sier nokså lite om hva som fikk henne til å digge Dylan i ungdommen ut fra sin egen familiesituasjon, eller hva som gjorde at hun sluttet å lytte, senere. Det ligger i bakgrunnen men spesifiseres ikke. Her og nå, i denne boka, er dette kanskje akkurat passe. Det er Dylan, ikke Solheim, som er i fokus. Det er godt levert og balansert.

Boka river ned myter om 60-tallet – og slutten er et godt eksempel. Forfatteren legger et teppe over gjesten i stolen. Ikke en natt i felles seng. Hvorfor tenkte jeg først, at dette var litt spakt? Burde hun ikke hatt en «våt drøm»? Jeg tror jeg tenkte ut fra fordommer om 60-tallet, som virker inn på de fleste av oss – at det den gang mest handlet om «sex drugs and rock’n’roll». Men Dylan var ikke et sexsymbol. Han var «hode», i motkulturen. En motkultur som handlet om samfunnsendring, ikke sex drugs eller rocknroll. Ikke først og fremst iallfall, selv om det kom som motvekter etterhvert. Solheim får dette fint fram, gjennom sin poetiske og symbolske tolkning av Dylan.

Alt i alt er denne boka en fin leseropplevelse som virker inn på leseren på mange plan, og som dermed er verdig adjektivet «glitrende». Dette er den beste boka om musikk jeg har lest på lenge. Den anbefales ikke bare ut fra interesse for Bob Dylan, men ut fra interesse for motkultur, ungdomsopprør og kjønn og likestilling.

Etter å ha lest Solheim, kikket jeg litt mer på Uncuts guide til Dylan. Jeg oppdaget ikke bare at 2 av 2 redaktører er menn, men også at 18 av 18 bidragsytere er menn (s 5). Tenk det, Hedda! Er det mulig!? Første gang en kvinne nevnes, er det under «Thanks to». Denne sterke mannsdominansen i Dylan-tradisjonen er interessant, og kanskje noe Solheim – og andre – kan komme tilbake til.

You might think, at the root of Heavy Rock lies power and chauvinism. Misogyny and male supremacy. Judging from some excess trends in heavy rock, later. With lyrics like “the soul of a woman was created below” (gleefully sung – though not written – by Led Zeppelin on “Dazed and confused”).

The truth is different. At the core of heavy was a mellow part. Even a feminine part, and sometimes a feminist perspective. This was in the early days of heavy rock, what we might call the “proto” stage of heavy. A this time, it was a tendency in rock, not yet a separate genre. Rock music was the key part of a counter culture which was still quite cohesive, not yet split up into music genres, different politics, or beliefs. Basically it united everyone under their long hair. Young men as well as women. It was OK for men to display more feminine traits, like expressing feelings and growing their hair long, like women. It was a case of the young and the new, against the old. With long hair and rock music as main symbols of the new. This was soon ridiculed for being childish and naive (a debatable point, compared to the more politicized counter culture later), and is important to understand, for why “mellow” came into the heart of “heavy”.

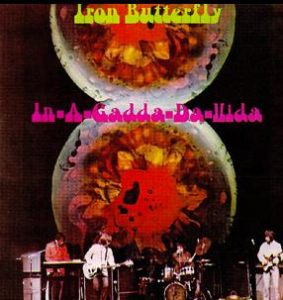

This mellow core of heavy is very evident on one of the first early heavy rock albums, Iron Butterfly: Heavy. Released in January 1968, before the debut albums of Deep Purple (July 1968), Led Zeppelin (1969), and Black Sabbath (1970) – the giants that later defined the heavy rock field. Things changed fast in those days, and before Iron Butterfly, what mainly existed was the “noise rock” of Cream and other blues-rockers. “Heavy” made heavy rock into a more distinct part of rock music, even if it was only in “proto” form, not fully realized.

The seminal Heavy album starts with two songs that criticize current society. One is about possession and property. The other is about going beyond that paradigm, going “beyond conscious power”.

So in fact the world’s first heavy rock album starts with a critique of the sense of possession, in love life, with these lines:

“When a man has a woman

And he doesn’t really love her

Why does he burn inside

When she starts to love another?

It’s possession

It’s possession

It’s possession

It’s possession”

The song isn’t just about possession in general, but about men’s feeling of possession, or in a more recent term, men’s feeling of “entitlement”. Even if the man does not really love the woman, he cannot take the rejection from her, and that she gives her love to another man.

Instead, he burns inside.

Why? It’s possession. The song refrain resembles a chant, a drone. Like a message burned in, through heavy chords and threatening music.

So, starting from the number one song on the first heavy album, we find a critique of masculinity and possessiveness. Associating men, property and fake love.

The album was recorded in autumn 1967, in the context of the turbulent and hopeful youth revolt of 1966-67, before the year of struggle and defeat, 1968. Youth were waking up everywhere. The proportion of long-haired among young men rose exponentially. Non-violent change methods were tried out on a large scale (like sit-ins, street theater, new forms of art, new economies). It looked like the authorities could accept the changes. “Socialism with a human face” was rising in Checkoslovakia.

You need a calendar to interpret these and other rock classics from the period, since the mood changed fast. 1966-67 was quite different from what came later. This is well brought out in John Savage’s book “1966” (Faber and Faber, London 2015).

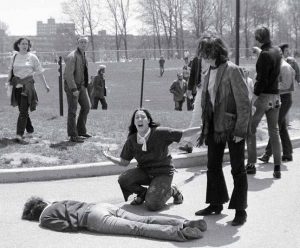

1968 was different and in many ways a shock. First, the counter culture / new left was defeated through street battles in Paris in May 1968. Then, in August, the Soviet Union invaded Checkoslovakia and squashed the new left-liberal democracy. The setback occured in the US and other countries too, in different forms, with the murders at Kent University in 1970 as the most symbolic event in the US.

Different rock bands and artists developed different responses to these events. What is common is a change of mood, due to the defeat. Some bands, like Steppenwolf, developed more political lyrics, like the critique of US capitalism on the album Monster (1970), and feminist lyrics also (e.g. For ladies only, 1971). Jefferson Airplane’s Volunteers (1969) was still vaguely hopeful, and similarly “revolutionary” in its view of society (with lyrics like “throw down the walls”).

For interpreting rock music classic albums, having a calendar or a diary at hand is a must. Even better, with in-depth music histories, like the Savage book.

Compared to groups like Steppenwolf, Iron Butterfly’s lyrics were less overtly political, keeping to the early counter culture message of going beyond ordinary politics (since this was associated with the establishment and the adult world). The music at the time reflected split opinions and diverse experiences in the counter culture, with some parts drifting towards more militant, adult and (traditionally) political response. Again, arguably, with very mixed results, or indeed rather bad results, even if the former youth revolt ideas were somewhat childish (e g Pink Floyd, with child-voices: “Why can’t we play today”. Why can’t our dream just become true).

Political and feminist lyrics, in the songs of Iron Butterfly, were more like an undercurrent. They speak like “heads”, in these songs. On this – maybe naive and childish – level, the song “Possession” spells out the problem, or a main part of it. The next song, “Unconscious power” points to the solution.

(The cover shows keyboard and singer Doug Ingle, main composer and writer, somewhat alone – on the other side of the great monumental ear in the middle)

(The cover shows keyboard and singer Doug Ingle, main composer and writer, somewhat alone – on the other side of the great monumental ear in the middle)

“We all want to prepare you

The unbelievable is going to happen

It will linger in your mind forever

Let this carry you wherever, wherever

Triggering the unconscious power

Removing all your inhibitions

Releasing complete freedom of thought

Sensations of every sense will prepare

With this you will see every thing

Triggering the unconscious power

Triggering the unconscious power

I say to you nothin’ for now

For now we know all

We know all

We know all

We know all”

The lyric is very optimistic, something unbelievable will happen. It strikes the tone of late 1960s optimism. And the change will be large, it will linger forever. You should let this knowledge carry you, wherever. Triggering your unconscious power.

Sounds superficial? Well, it was before “new age” ideologies. Here are young long-haired men trying to psychoanalyze the world. Very limited, it may be said. In fact this was often said, at the time also, about the “childish” and “simple” aspect of the youth revolt and early counter culture. It was basically naïve. Some counter culture artists like Frank Zappa contributed to this idea. Hippies were all fake.

But note what these two songs are doing.

First, they are musically far from hippie territory. There is a feeling of anxiety and even terror, not a cozy “summer of love”, in the music (a worthy runner up is Blue Oyster Cult: This ain’t the summer of love, on the album Agents of fortune, 1976).

There is the typical impatience of the late 60ies – go right to the core. Just play, even if you don’t know how to do it.

They dig into a feeling, a burning inside, something many people recognize, not least, men. They start with a widespread experience, a phenomenon. They describe it vividly, like the pop art emerging at the time. It’s concise. They don’t make extra words, or opinions. They just jump right into the explanation. This burning has to do with possession and property. They describe men’s sexual jealousy and sense of property as a disease, even if they don’t use that term.

It was certainly enough to make long haired parts of the youth of middle-class America and elsewhere wake up, even if it did not make a hit. The band sold millions soon after, with the album “In a gadda da vida” (1968). Many Iron Butterfly songs are harsh condemnations of an oppressive society. “In a gadda…”, as a contrast, had a positive message, pointing to a better future. It caught the imagination of young people in the US, becoming a marker of youth culture influence.

This ability to catch “surface” phenomena, and (to some extent) point to better solutions, was a main reason why youth and counter culture movement expanded rapidly from the mid 1960s onwards. Like using the long hair to go beyond traditional political divides. The tendency was leftish, but this was to be the “new” left, not the old. Within the youth movement, 1964-67, the main target of critique was very broad, it was the adult world, fake family life and consumer society (Frank Zappa: “plastic people”), rather than a specific (adult) political target like capitalism or class. Gender was also mainly implicit, even if the young men growing their hair longer were soon ridiculed for “looking like girls”. The underlying feminine / feminist current of the 1960s changes has not been sufficiently studied.

So why does Iron Butterfly close their “Unconscious power” song by saying “I say to you nothin’ for now”? And repeating this point? This can be interpreted as “headspeak”.

The notion of the “head” was important in the counter culture. Heads were thinking people or intellectuals guiding the movement, but they should not become a new upper class. So for a head to withdraw, and say, I say nothing for now (since we are right at the beginning), could be the right thing to do. Very cool. Rather than preaching or predicting. The message in the song is very clear: you can see for yourself. “We know all”. If only we let in our “unconscious power”.

A major counter-argument, to what has been said before, is that Iron Butterfly’s “Heavy” album does not really represent the birth of heavy rock. For this, one should listen to albums like the first Black Sabbath album, instead.

This is true on one level. The “heavy” sonic signature is more recognizable here, than on Iron Butterfly’s Heavy. Black Sabbath goes in the direction of “doom and gloom” – towards heavy metal, and dark metal, the notable 1970s trends. On the other hand, they also lean backwards on the blues of “noise rockers” like Cream. Not very inventive, compared to the best Iron Butterfly melody lines, although more distinctive and genre-defining. Bands like Procol Harum also picked up some of the doom and gloom trend, although they cannot be classified as founders of heavy rock.

However, even if Black Sabbath was maybe the first to trademark an “evolved” heavy sound, other bands evolved in other ways, and the “first” position can be questioned. If we allow the scope of “proto” heavy, the roots of the genre, Iron Butterfly’s first album stands strong.

For understanding the evolution of counter culture music, The Byrds is a useful case. Even if it did not evolve into heavy rock, but rather, early “Americana”, country and western influenced music.

The Byrds was a key link, making mid-60ies folk music into folk-rock-pop hits. They started out singing Bob Dylan’s songs, making a major hit with a pop-rock version of “Mr Tambourine man”, with several weeks at the top of the single sales lists. This was followed up by others, like “All I really want to do”, “My back pages”, and “Chimes of freedom”. However, the public gradually got tired of the somewhat stereotypical Byrds treatment of Dylan’s songs, and sales dwindled. Still, they managed to get his main message across, as a foundation for further rock development. Dylan took up the challenge, one might say, with “Like a rolling stone”, and others. Dylan’s insights came to stay, in rock music development, partly thanks to the Byrds.

The Byrds took much of their material from Bob Dylan’s “Another side of Bob Dylan” album, 1964, in some ways his most revolutionary or radical album, still keeping to his “protest” roots.

Do you think the “mellow core” of heavy rock is only a special back-then case? Don’t be too sure. There is more “mellow stuff” lurking behind the hard, heavy and metal doom lyrics and headlines. This is the subject of another blog post, but two recent examples deserve mention.

Rammstein, on their recent (untitled) album (2019), sings about the abuses of German power through the times (Deutschland) and the violations in the name of religion (Zeigt dich). They are critical, but also mellow (Radio).

Opeth, on their last album “In cauda venenum” (2019), are similarly critical, with some doom and gloom as behoves the genre, but they are also mellow, for example in the track Dignity (Svekets prins), using a sample from prime minister Olof Palme’s new year speech, some years before he was murdered. Palme talks about the inner anxiety (uro) one feels, even if social democratic society seems to go well. Opeth – bless them – takes it on, from there. Here there be tygers.

I et innlegg i Aftenposten impliserer Bernt Hagtvet at Mao var den største forbryteren i det 20. århundret, eller iallfall, at han skapte den største forbrytelsen, ut fra at “Det store spranget” skapte sult og ledet til kanskje 45 – 70 millioner døde. Mer enn noen annen humanitær katastrofe i århundret.

https://www.aftenposten.no/meninger/kronikk/i/Op9kWA/et-diktatur-speiler-seg-selv-bernt-hagtvet

Hagtvet bygger særlig på Frank Dikötters bøker, “Mao’s Great Famine. The History of China’s Most Devastating Catastrophe 1958-62 (2010)” og “The Tragedy of Liberation (2013)”.

Hagtvet oppsummerer at materialet “viser at Mao Zedong er den hovedansvarlige for sultkatastrofene. .. Tanken var å gi den kinesiske økonomien et elektrosjokk og ta igjen Storbritannia på en generasjon eller kortere.” Det gikk dårlig, og ledet til sult.

Hagtvets (og Diköttters) analyse av det kinesiske kommunistpartiet er viktig, og stemmer med en del andre historiske kilder i min bokhylle. Men den bør nyanseres og ses i sammenheng. Det kan virke som om Hagtvet har en egen agenda, i forhold til folk i Norge som “svermet” for Mao. Dette kan – igjen – kanskje være OK, men det må bringes ned på bakkenivå. Hagtvedt nevner norske intellektuelle som – etter sigende – svermet for Kina (f eks Johan Galtung). Det blir for snevert, og kan oppleves som mobbing.

Mer prinsippielt setter jeg et negativt fortegn framfor en fortelling som skal gjøre Det store spranget til den største menneskeskapte forbrytelsen i det 20 århundret.

Hva med holocaust, Hagtvet? Hva med det industrielle mordet på hele folkegrupper? Dette er da mye viktigere, enn bare de totale tallene for ofre av ulike staters mer eller mindre forbryterske politikk?

Ann Applebaum, amerikansk historiker, analyserer dette i sin bok om det sovjetiske Gulag-systemet med konsentrasjonsleire. Ja, skriver hun, systemet drepte flere, i kombinasjon med sult osv, enn det tyske nazi-systemet. Stalinistene hadde arbeidsleire der mange døde – men nazistene laget dødsleire. Uten parallell i Gulag-systemet. Stalinistenes leire var i hovedsak “økonomiske”, skriver hun, mens nazistenes leire i hovedsak var “straffende” (punitive). Selv om andre feilslåtte og autoritære inngrep skapte store dødstall, er det ingen tvil om at nazismen var den største forbrytelsen mot menneskeheten. Nazismen drepte ikke bare millioner av jøder, påståtte kommunister, demokrater, avvikere og oppviglere (i tillegg til såkalte “undermennesker” inkludert funksjonshemmede) tvers gjennom sitt maktområde, den skapte også en situasjon der 50 millioner, eller mer, måtte bøte med livet, i annen verdenskrig. Med mange flere sårede, ødelagt fysisk og emosjonelt.

Å sammenlikne Det store spranget, med nazistenes gassovner og folkedrap i Europa, holder altså ikke.

“Brutto” statistikk om dødelighet og andre tap er ikke nok. Intensjon og formål må med i bildet. Hitler ville drepe folkegrupper. Mao var ikke ute etter dette. Det er en forskjell. Både Hitler, Stalin og Mao var mer enn villige til å “gå over lik” for å få sine planer gjennom. Alle tre sendte opposisjonelle til konsentrasjonsleire. Men bare Hitler og nazistene fant på hvordan leirene kunne utvikles til det de kalte “den endelige lønsningen”; industrielt massedrap på jøder og alle andre som sto i veien for regimet. Altså en ny type overlagt massedrap.

–

Jeg er ingen detalj-ekspert på humanitære forbrytelser og folkemord, men har jobbet noe med dette, som historisk orientert sosiolog. og har bidratt til forskningsutviklingen, bl.a. her:

I et kapittel kalt A Theory of Gendercide, drøfter jeg ulike forhold som virket inn på nazistenes drapsmodell, med kjønn som del av bildet. Jfr. Jones, Adam, ed.: Gendercide and genocide. Vanderbilt University Press, Norman, p 62-97, 2004.

En annen nyttig kilde, for å forstå de indre forholdene som skaper folkemord, er Hannah Arendts bok Eichmann in Jerusalem. Jeg leste den om igjen nylig, og det var vel verd det. Eichmann og andre naziforbrytere prøvde å komme unna, ved at de ikke hadde motiv, de var jo glade i jøder, og f eks Eichmann drev egentlig et slags reisebyrå, med transport av jøder. Lite visste han om at reisen endte med døden. Det var ikke deres bord. – Denne klassikeren fra 60-tallet er minst like viktig nå, som da den kom ut. De underordnetes forsøk på å “tilpasse” seg nazistene er del av bildet.

Applebaum’s bok er en moderne klassiker, etter mitt syn. Den vant Pullitzer-prisen i 2004 (se https://www.pulitzer.org/winners/anne-applebaum. Sjekk den ut: Applebaum, Anne 2004: Gulag – a history. Penguin, London. Reprintet mange ganger. Ikke rart.

Boka bidro til å etablere et nytt fagfelt internasjonalt. Mer presise studier av autoritære regimers mishandling av dem som står i veien for deres allmektige ambisjoner.

Derfor er slike studier av konsentrasjonsleire og straffesystemer særlig viktige, i diskusjonen om humanitære sammenbrudd, overlagt drap, forbrytelse og straff. De utforsker hva regimet gjorde i praksis, med motstandere og avvikere. Et slags røntgenbilde, av diktaturet.

Norske forskere, bl.a. Kristian Ottosen, var tidlig ute på feltet. Ottosens monumentale utforskning av konsentrasjonsleire i Tyskland og Japan er dessverre såvidt jeg vet fortsatt bare tilgjengelig på norsk. “It’s a shame”, som man sier. Internasjonale forskere hadde hatt nytte av dette materialet.

Ottosens bøker omfatter:

- Natt og tåke. Historien om Natzweiler-fangene, 1989

- Liv og død. Historien om Sachsenhausen-fangene, 1990

- Kvinneleiren. Historien om Ravensbrück-fangene, 1991

- Bak lås og slå. Historien om norske kvinner og menn i Hitlers fengsler og tukthus, 1993

- I slik en natt. Historien om deportasjonen av jøder fra Norge, 1994

- red. Nordmenn i fangenskap 1940–1945, 1995 (ny utvidet utg. 2003)

- Ingen nåde. Historien om nordmenn i japansk fangenskap, 1996

- Nasjonalhjelpen. Et lys i mørket, 1997

- Redningen. Veien ut av fangenskapet våren 1945, 1998

- Den annen verdenskrig, 2000

- Motstand, fangenskap og frihet. Erindringer 1940–45, 2005

Jfr https://nbl.snl.no/Kristian_Ottosen

Author at the Margareta Church ruins, in the Maridalen valley north of Oslo, early March 2020

Blog post written March 16, updated March 22 and April 6, 2020

“There is no such thing as society” – ? The social profile of Covid19

A virus does not have any idea of social class, status, and other forms of ranking or hierarchy in human society. It just looks for bodies where it can survive and multiply.

The virus spreads to “somebody”, not just “anybody”, in our society. It doesn’t affect all groups in the population equally.

It spreads through people who create society through their practical lives.

The neoliberal idea that “there is no such thing as society” (Margareth Thatcher), that we are only individuals, is not very convincing in these times of trouble.

Epidemics have a social class profile, and this is an important perspective to keep in mind, as argued by Svenn-Erik Mamelund at Oslo Met, and other researchers. Mamelund warns that the effects of the pandemic will be worse, in lower income groups https://www.klassekampen.no/article/20200316/ARTICLE/200319974

The total cost of epidemics is usually higher among poor people and regions. This is why, as the WHO warns us, we need to worry about Africa and the poor world, in the current situation, not just the spread of the virus in Europe and the US. Poor countries will be even worse hit, and this will hit back on us, unless we can break the cycle.

The new corona virus is socially blind, it just jumps to the nearest somebody. Workers in high-contact jobs are more prone to get it, and people with more social contact. The transmission as well as the resulting Covid-19 disease has a social profile, with the death rate much higher among some population groups than others.

Although the patterns of disease transmission and development are partly cloudy, two facts emerge beyond doubt. 1) the disease selects by age, older people are more likely to get heavier symptoms and are more likely to die from the resulting worsening of the disease. 2) underlying health problems like heart problems and diabetes are also clear negative factors increasing the chance of dying from Covid-19.

Men go first

It is also clear that the death rate from the disease is higher among men than women. Yet the reasons for this are still in the dark. They are not well clarified.

It seems that, once again, “gender” is a topic that stands at the end of the queue, regarding research, even though, empirically, it is central.

I have looked for research on men’s larger death rate from Covid19 since late February. It is only in the last weeks that the issue has shown up more frequently, mainly in the media, citing recent and still rather fragmented research.

The numbers are only partly clear. I have not seen exact international statistics, regarding the gap between women and men’s chance of dying from the disease. My overall impression is that men stand a one and a half chance, to a double chance, of dying from the disease, compared to women. According to the Chinese evidence (based on the first 55 000 deaths), the chance of an infected man dying from the disease was 168 percent the chance of a woman dying from it (crude fatality rate). A more recent study (72 ooo deaths) shows a very similar pattern, 165 percent chance.

Why?

The first reports, from China, on the larger death rate among men, were tentatively explained by the much higher proportion of smokers among men compared to women in the country. Now, reports from Italy indicate that men are even more prone to die from the disease compared to women, than in China. The “extra male burden” of the new disease is maybe even larger in Italy than in China. Yet in Italy, smoking is more gender-balanced than in China. From age 60 upwards – the main part of the new disease death cases – the proportions of women smoking is circa 80 percent the proportions of men. The gender gap in smoking seems too small to explain the large fatality difference. See https://www.statista.com/statistics/501615/italy-smokers-by-age-and-gender/

I wrote about this in the original version of this post some weeks ago. Now (April 6) I see the same point picked up elsewhere also, e g in this informative text: https://www.wired.co.uk/article/coronavirus-death-men-women

There is recently more interest in gender issues, and I notice a move away from purely “external” explanations, like smoking, towards more integrated approaches. Even if damaged lungs doesn’t help, its not enough to explain the gender difference. The same goes for other biological or other disease factors. They are important, but they don’t explain all. Quoting from the above paper:

“Ultimately, biology, lifestyle and behaviour are all likely to play a role in the spread and impact of Covid-19. But it will only be possible to understand the exact differences between men and women once more countries produce and make available sex-disaggregated statistics on infection and mortality.”

Possibly, fatal cardiovascular disease, more common among men than women, is a more important factor behind the different fatality rates, than smoking. Studies point to a higher fatality among men at this point, maybe twice as high as women, and cardiovascular disease is the number one factor increasing the complications of the new disease, ahead of diabetes, and others, according to Chinese studies. However, this is probably also only part of the picture. The fatality from cardiovascular disease becomes more gender-balanced, among older people.

There are other medical or biological explanatory factors too, including better immune systems among women, and maybe hormone and chromosome differences, but the picture is still far from clear (as far as I can see).

Patterns of behaviour – our old friend “society” – most probably plays a large role.

Men and health

According to men and masculinities research, men are in situations that may work against good health, and often adapt to patterns of action and practice that increase the health problems. Men’s health behaviour is more often in the high risk zone, than women’s behaviour.

A dramatic example of this rule comes from studies of suicide. These show an almost universal global pattern – men suicide more often than women. Recent studies have also mapped suicide attempts, not just suicides. Here, the situation is the opposite. Women, not men, are most prone to attempt suicide. These studies show that when people consider suicide, men tend to do it, while women more often stay on the brink, they may attempt it, but they don’t go through with it.

Similar patterns can be found in other health-related behaviors. Compared to women, men typically take less (and later) contact with the health system, and are less open about problems. Even in gender-equal Norway, if a couple has a problem, it is typically the wife contacting the family councelling or therapist, dragging the husband along.

Greater fatality among men compared to women in different age groups and for different diseases and causes has been reported e g by the UK researcher Alan White (https://alan-keith-white.blogspot.com/2019/07/mens-health-and-womens-health-emerging.html).

These are relevant factors, even if they may not play the main role for the Covid19 deaths today. The health and social evidence are important parts of the whole. Another important data source on men and health is the International Men and Gender Equality Study (IMAGES, cf. https://promundoglobal.org/programs/international-men-and-gender-equality-survey-images/

It should be noted, that the idea of a “zero sum game” in terms of gender and health is rejected by most health researcher, even if it lives on in the media. Women’s health does not improve by men dying before them (or vice versa). Instead, women’s and men’s health problems should be seen in connection, and reduced in terms of better health behaviours from both (all) genders. Yet the idea stays on, in today’s media and debate.

According to the evidence regarding gender conceptions and bias, “fundamentalist” gender ideas may become stronger, in times of crisis or perceived danger. Crises may create “social panic”, a pattern mapped by researchers already in the 1960s. With more anxiety, studies show, there will be more of a backwards leaning on what is “safe”. Strict conservative gender rules are often considered “safe”. The evidence at this point is not conclusive (there may be gender innovative responses also), but it is clear that gender conservative fallback is a recurrent trend.

Generals planning for the last war?

Imagine what would happen, if women’s death rate from the new disease was almost the double of men’s. Would there have been an outcry? I think so. In gender-equal countries like Norway, at least.

I find it strange, based on the death rate evidence, that “male” is not included, and still not much highlighted and discussed, among the new disease risk factors.

Why not?

Is it mainly due to gender conservativism and a kind of automatic thinking? Men are more prone to die, this is part of the male role, with the man as protector and provider? We are “at war” with the virus, we are told. And men / soldiers are of course the ones most likely to pay their lives. So, the empirical red light warning, the much higher death rate among men, has mainly passed under the conceptual radar.

Class experts tell us that Covid19 will hit poor people worst. Gender experts tell us that women will be worse hit. This has been very visible in Norway, and internationally, as the media debate has taken up research issues, with more peope concerned about the “how” and “why” of the disease.

I think these experts, opinion leaders, or “generals”, are mostly quite correct, regarding strategy, or overall impact. Yet generals need to know about tactics too. Tactics is not about what happens some years ahead. It is about what happens today and tomorrow. The current empirical picture of transmission, hospital treatment and death from Covid19.

We need to untangle the overall long term effects of the disease, from the actual happenings here and now. Especially, we need to distinguish between the transmission group and the serious impact group (those who get seriously ill, and may die).

For a dramatic example, compare the Black Death. This also probably first started among poor people – we don’t know. It spread through tradesmen to Europe. A typical first stage is transmission through people with money and contacts.

This is now replicated in the European evidence including Norway. Here, ski tourists from Italy and Austria brought home the virus. Likewise, with the so-called Spanish Flu after World War 1, the origin seems to have been in the US, spreading to Europe and the rest of the world mainly through the military. Poor people, and women, usually get the largest total costs from epidemics, but the transmission, especially in the early stage, is another story.

Top down transmission

Instead of the poorest and the lower classes, we obviously have a situation with a “top down” type of distribution of the virus, e g in Norway.

It started with people with money and contacts, mainly. And the fatality rate seems to be quite high, in these groups also. The lack of attention to the top down spread is evident in Europe and elsewhere with leaders in isolation, or infected.

Crying wolf regarding the working class, or women, is important in an overall perspective, but may be misleading, here and now. To understand and reduce pathways of infection and death from the disease we need to look at the upper/middle class, people in occupations with much contact – and men.

There are two different main groups involved, in reducing the total damage to society – the transmitters, and the seriously affected. Their social profiles started quite similar, but are now more diverse, as the disease spreads downwards in terms of social class, gender and ethnicity.

This is now quite clearly confirmed by local evidence from Oslo, capital of Norway. At first, the transmission was largest in the most affluent parts of the city. Recent evidence shows a shift towards the less affluent parts. Maybe, in some weeks time, these areas will be on the top of the list of infections per capita. The transmission will still be somewhat top-down, probably, but less so, than in the first phase.

This prediction fits the international Covid19 statistics (see e g Worldometers). Here, the numbers still read like a “rich world” club of transmission and deaths, with the rich world country deaths outnumbering the poor countries, and with the “epicentre” moving, with US rising fast, and Europe slowing down, while poorer countries – so far – have far lower rates.

This will most probably change, according to top down transmission class and gender analysis and historical epidemic evidence. We shall see. What is clear, here and now, is that top down transmition is shifting into wider transmition, going further out and downwards in terms of social status (class, gender, and others).

It seems that some of the bias and outmoded thinking in the first stage of the disease – where the gender death rate imbalance was almost totally overlooked (in February, early March, in my evidence), and the top down transmission evidence was mainly ignored (again, in my impression) – was due to the way expert researchers have conceptualized their work. They are into “gender”, for example, but in a quite restricted way, where gender mainly means “women”. Where men are assumed to be of less interest, and/or less gender-equal.

This gender-means-women bias is quite typical, in my experience, in international organizations, for example. Likewise, in terms of class, there is a common response, class means the lower class. Is this approach wrong? On the whole, no. But like I said, it is not the full picture. Tactics differs from strategy. Tactics involves the empirical material, here and now. At that point, experts have been slow to respond, in my view.

Since women generally live longer than men, and age is the number one factor increasing Covid19 fatality, we might have expected more women than men dying from it. Yet this is not the case. This underlines the need to investigate gender differences further.

Summing up

Clearly, better knowledge of the “hidden” gender dimension is needed. Researchers and experts need to cooperate, to create the best possible socio-medical-biological mapping of how Covid19 spreads, how it develops into serious illness, and takes lives – and how it can be reduced.

It is now clear that this will be a long-term pandemic. Gender is one of the central variables regarding the death rate from Covid19, and the reasons for this, still mostly unknown, are important for research and prevention.

The social part of the mapping of Covid19 should include social class, gender, ethnicity and other factors. This is vital and urgently needed. Gender may be a key factor, to reduce the disease and the social and economic cost of the pandemic.

Today (April 4), in Norway, there is really no telling how many have been infected by the virus. This is because testing equipment has become scarce and testing is not at all on the level of the WHO recommendation (“test, test, test”). So, experts and health workers are trying to trace transmission paths through a very limited number of test numbers. This is clearly far from optimal.

But at this stage, a social probability map – and guidelines – who, to test – is very important. Where to look, to find the transmitters. Social science cannot predict this exactly, of course, but it can help out, making it more likely that the tests that are actually done, find their target – the transmitters.

Author following Covid19 news on a mobile phone, April 6 (reading some good news, maybe light in the tunnel, now.)

Harriet Holter and Erik Grønseth

Norwegian and Nordic gender research was often radical and innovative in the 70s and 80s. Erik Grønseth and Harriet Holter were two of the pioneers, in Norway.

In this 1987 paper, Harriet Holter discusses Metoo problems, long before more open information was available, long before Metoo.

I cannot find this text on the web, so in this age of open access, I make a copy. You can find it here.

Holter Harriet Seksuell kultur overgrep og gjensidighet 1987 IMG_20200310_0001

Six years ago, in a paper called “What’s in it for men”, I published results from a new data base of 81 European countries and US states, showing that higher levels of gender equality were associated with better health for men, not just for women.

One noteworthy finding was that men’s rate of suicide, compared to women’s rate, was highest in the most gender-unequal countries and states. In other words, the idea that men are worse off, if women have more say, was distinctly disproven, in this (macro) evidence.

Some of the main findings are summarized in this graph, made from the data base:

See: Whats in it for men, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1097184X14558237

Now, a new US study points in the same direction. The study shows that “high–traditional masculinity men were 2.4 times more likely to die by suicide than non-HTM men”.

The study builds on a large health questionnaire that included masculinity-related items. High-traditional masculinity is an index based on items like “not crying, physically fit, not moody, not emotional, liking yourself, fighting, and risk taking”. The survey included 20745 adolescents in 1995 and in 2014 was matched with death records using the National Death Index. This gave a sample of 22 suicides. The researchers claim that the HTM pattern is very clear, and outperformed other factors. HTM men “were 1.45 times less likely to report. (..) There was no association between HTM and suicide attempts. High–traditional masculinity men were slightly more likely to report easy gun access (..) and had modestly lower depression levels.”

My 2014 paper, pointing to the connection between traditional gender, gender inequality and relatively higher suicide rates among men, is not referred to in the new study. They probably don’t know about it. Their independent conclusion is all the more interesting.

My evidence makes it probable that the relatively higher rate of male suicide in gender-unequal countries and states is related to traditional masculinities and male roles. Even if the HTM scale is only a proxy (somewhat debatable), it points towards a low level of gender equality in society.

This can be connected to statistics showing that men and women “attempt” suicide fairly equally – but that men actually go on and do it. There is no more attempted communication. This “gendered closure” is higher in countries with low levels of gender equality. The tendency cuts across different levels of economic progress and income equality. Gender equality is an independent factor, working on its own, according to the “Whats in it for men” macro data, as well as other studies.

Suicide statistics are also influenced by the availability of “effective/masculine” ways of ending one’s life, like firearms and a culture that enhances their use, and many other factors, that however also often have a gender aspect.

In sum, the evidence points to the potential of a substantial reduction of male over-suicide by gender-equal type of measures, e g focused on communication before the attempt, “don’t do it even if you try it” and curbing “macho” tendencies in suicide contexts.

If men had copied women’s more hesitant and communicative suicide patterns, rates would probably have been much lower.

However, we do not know how closely low gender equality in society and traditional masculinity among men are actually connected. Attempts to single out “traditional” or even “toxic” masculinity can be non-nuanced and counterproductive in some contexts.

Note that my macro data did NOT explain why suicide was higher or lower in gender equal countries. That analysis did not show a clear pattern. What DID show a clear pattern, was that the tendency of men to suicide more often than women, or the rate of “male over-suicide”, was clearly and strongly connected to low gender equality.

I would like to thank Kelly Fisher, MA student at my center, for the link to the new study.

At last, very delayed, I have read this 60s classic:

I am embarassed, I should have read it long before, this is glittering analysis, a beacon of a book, everyone should read it, its a true classic of the 60ies.

What does it say, more exactly?

Eichmann did not start out as a killer. On the contrary, his job was to “export” Jews – to somewhere. He got clever at this, threatening and pushing Jewish councils, so they cooperated, and paid much of the price for the “export”. At the start, the end of the export was some other place. Later, it meant death. Eichmann claimed he did not know. He was only the master of the trains and transportation, shipping out Jews, to “somewhere”. His main worry was that the Nazi hierarchy didn’t recognize his effort, to get this whole system going, based on his former recruitment of Jewish participation to the migration deals. The bigger bullies in the Nazi chain of command did not fully recognize his manly efforts! This was what most worried Eichmann, even as he sent millions of Jews to the death camps. This is the “banality” that Arendt describes so well.

Take as example – Iron Butterfly.

How strange, now, to listen to this American music, compared to today’s developments. How strange to hear so much relevant about today, even long before.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-3569220-1465510845-1921.jpeg.jpg)

Try “In the time of our lives”, “Filled with fear”, and “Real fright”. Check “Unconscious power” on their first album Heavy, and “Possession” (avoid the repeated-to-death “In a gadda da vida”).

These are songs from the counter culture, way back when. It did not win the agenda. Still, interesting listening. Sometimes even more relevant today.

Democracy is on the defensive, in the world today. Not only is the proportion of authoritarian and totalitarian countries growing, but the dissatisfaction with democracy in democratic or semi-democratic countries is growing too.

A new report based on public opinion surveys shows the growing dissatisfaction with democracy in many parts of world. Except for a fairly small group of countries, mainly in the European north, many democratic countries show a decline in satisfaction with democracy over the last years. Notable cases include the US, Brazil and the UK.

A brief news report here: https://www.bbc.com/news/education-51281722

More on the method here: https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2020-01/uoc-gdw012720.php

Full report here: https://www.bennettinstitute.cam.ac.uk/publications/global-satisfaction-democracy-report-2020/

The report discusses institutional and other factors behind the decline in support for (or trust in) democracy.

Surprisingly, gender equality is not mentioned as a background factor, even though many countries on the top of the list, with the largest satisfaction with democracy, are also on the top of the global gender equality indexes, like Norway, Denmark, Finland and Sweden. (Cf http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2020.pdf )

The top performing group in this study is a mix of gender equality and economic benefit, it seems, including Switzerland and Luxembourg (cf report figure 6), but the correlation with high levels of gender equality is very noticeable – and yet not noted in the report.

Gender equality is probably strongly associated with well-functioning democracy in today’s world. It is a cause, not just an effect, of democratization. It is an integral part of democratization as research pioneer Ronald Inglehart (in his paper Gender Equality and Democracy) noted twenty years ago. Gender equality helps pave the way for democracy and helps extend its meaning from formal measures to real changes towards a fair society, working for all. Gender equality is associated with better life quality, for men as well as women, controlling for economic level and income distribution (see Read more, below). Today, gender equality is a “filter” against build-up of social inequality and social conflict. Its not perfect, but it is there.

The importance of gender and gender equality has been neglected in many areas including democracy research. This needs to be changed – we need more research on this key link.

Read more:

Holter, Øystein Gullvåg 2014:

“What’s in it for Men?”: Old Question, New Data

Men and Masculinities 17(5), 515-548